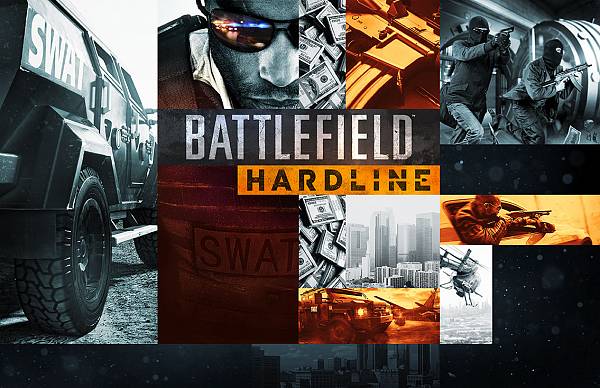

In the late 1990s and early 2000’s, first person shooter video games focused thematically on World War II with major franchises like Medal of Honor, Call of Duty, and Battlefield. Things started to change around 2005 when the Battlefield series released Battlefield 2: Modern Combat and the change in focus was cemented with the blockbuster release of Call of Duty 4: Modern Warfare in 2007. That’s pretty much where the genre has lived for the last 10 years. Recently, however, the Battlefield franchise has decided to shift focus again with their newest title Battlefield: Hardline which release earlier this month. The disturbing twist in the newest game, which you can see in the trailer, is that instead of soldiers fighting on a battlefield we now get militarized cops.

Obviously, this is not the very first time a video game has been controversial. I’m a gamer, but there are some games that I refuse to play because the depiction of violence reaches levels that I think are a little sick. Just to give a very simple example of that: I have played just enough of the Grand Theft Auto franchise to know that it will never be allowed in my home. I also have all kinds of political issues with the Call of Duty franchise,[ref]I will resist a tirade on the self-loathing anti-Americanism of the series and merely point out that in the Modern Warfare story arc, the bad guys always end up being the Americans and the playable American characters always die.[/ref] and even though the most controversial level of that that series[ref]The level is called “No Russian,” In it, you play an undercover CIA operative helping to massacre unarmed civilians in a Russian airport.[/ref] was made by a high school buddy of mine, I opted out. And these are, relatively speaking, the tame examples of controversial video games. The really nasty stuff I won’t even go into here.

So I’m not going to hyperventilate and argue that Battlefield: Hardline is the worst thing to have happened in video games. It’s not. It’s still pretty disturbing, however, and the video game press has taken notice. Chris Plante writes in Polygon:

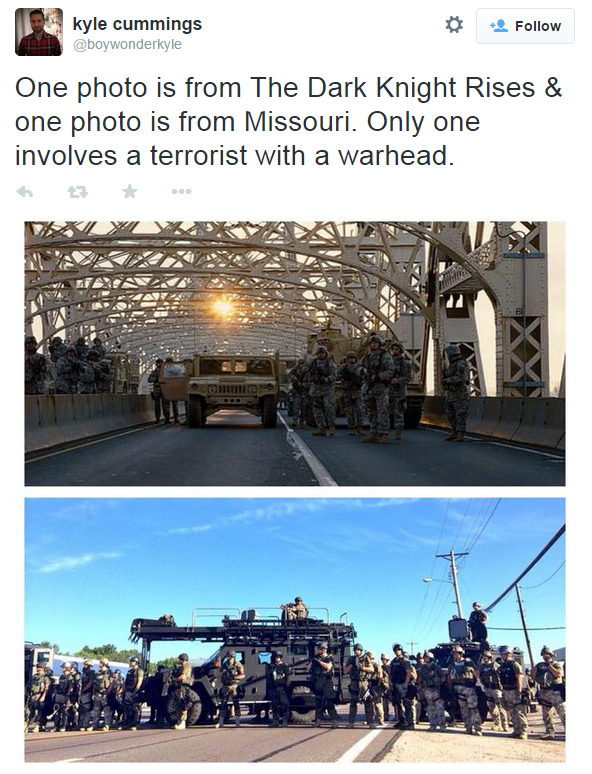

You used to be able to tell the difference between a cop and a soldier by how they looked. Soldiers had fancy gear, camouflage and heavy weaponry. Cops had a badge with their name and officer number. Times have changed, and now cops at a peaceful protest can look like the soldiers saving Gotham from a nuclear weapon.

The creators of Battlefield Hardline, while researching the militarization of the nation’s police force, understandably began to view the devices used by Americans against Americans as novel and fun. After all, they look identical to those being used in their previous games against fictional terrorists.

Here’s the image he was linking to, btw:

Now, there are some who have gone a little farther and suggested that video games like this in some way cause police militarization. I think that’s a little silly, in much the same way that I think blaming video games for causing general violence in society is pretty silly.[ref]Biggest problem: as video games get more realistic and more violent and more popular, the actual rate of violent crime is trending downward.[/ref] Thus, I largely agree with Erik Kain’s take in Forbes:

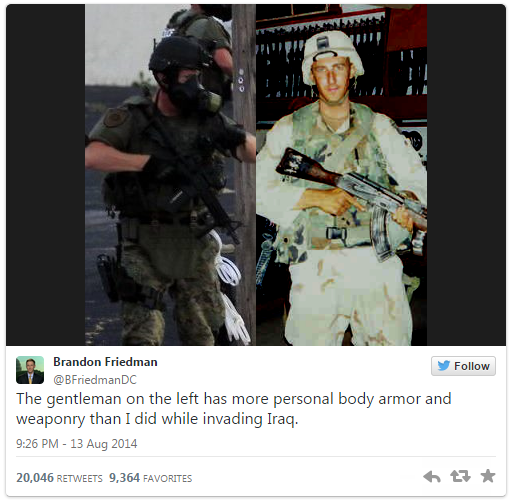

Alan Jacobs, writing at his blog, makes the connection between the Ferguson police and Call of Duty:

“I want to suggest that there may be a strong connection between the visual style of video games and the visual style of American police forces — the “warrior cops” that Radley Balko has written (chillingly) about,” writes Jacobs. ”Note how in Ferguson, Missouri, cops’ dress, equipment, and behavior are often totally inappropriate to their circumstances — but visually a close match for many of the Call of Duty games.”

Jacobs is arguing that the culture of first-person shooters—and the aesthetic—is being imprinted on our police forces. It’s not a bad argument by any means… [but] I’m not so sure.

Kain goes on to argue that the reason for his skepticism is simply that “these problems are structural rather than cultural.” He goes on:

The War on Drugs and the War on Terror are essentially the same war when it comes to beefing up law enforcement at the expense of personal liberty. The War on Drugs already provided a good excuse for law enforcement to overstep its bounds; the War on Terror has led to much better armed police forces and the sprouting up of SWAT teams all across the country.

There are now over 100 SWAT team raids a day in the United States, mostly for non-violent offenses, and often leading to horrible things like police throwing flash bang grenades into a baby’s crib, or the killing of a seven-year old girl while a SWAT team raided the wrong apartment looking for a murder suspect (who was in the apartment above and gave himself up without violence) while A&E filmed the entire event for a reality TV show.

The problems are deep and they are profound, but they are not likely to be caused by video games. On the contrary, what creeps me out about this game is simply that it reflects a kind of social nonchalance and acceptance of some pretty horrific, unnecessary police violence not to mention the systematized discrimination that goes along with it.[ref]I’ll be writing more about that very soon.[/ref] Consider what Scott Shackford had to say about gamer opinion in his piece for Reason:

The folks behind Battlefield Hardline might want to check out our Reason-Rupe analysis of poll responses by frequent gamers. We found they’re more likely to be concerned about the militarization of the police. From our survey, 70 percent of gamers think it’s too much for police forces to have access to military equipment and drones as tools for crime-fighting, compared to 57 percent of non-gamers. And nearly two-thirds of the gamers we polled believe that police officers aren’t held accountable for misconduct.

Shackford’s point appears to be something like: Hey, Battlefield, you’ve picked the wrong demographics here. Gamers are libertarian. They won’t go for this. But the logic is really kind of backwards. Gamers do tend to be left-libertarians, but that didn’t stop the game from becoming the #1 biggest selling 2015 launch (to date) in the UK. I’m not sure what the numbers look like in the US, but it’s clear millions of gamers are snatching up copies. If these guys–more suspicious of police militarization than the Average Joe–are untroubled by the game, what does that say?

So no: I don’t think violent video games lead directly to real-world violence and I doubt that a game glorifying police militarization is going to lead directly towards even more police militarization. But, even if Battlefield: Hardline is largely following a trend rather than setting one, it may still play a role in normalizing the police militarization we already have. For centuries we’ve had an American tradition of separating military and police forces, but that tradition doesn’t mean much anymore if the police and the military have become indistinguishable.

At this rate, I have to wonder if rising generations will even have a conceptual notion that there was ever a time when the police didn’t roll around in armored personnel carriers with fully-automatic weapons. And I think that just makes it a little bit harder to reverse the trajectory we’re currently on.