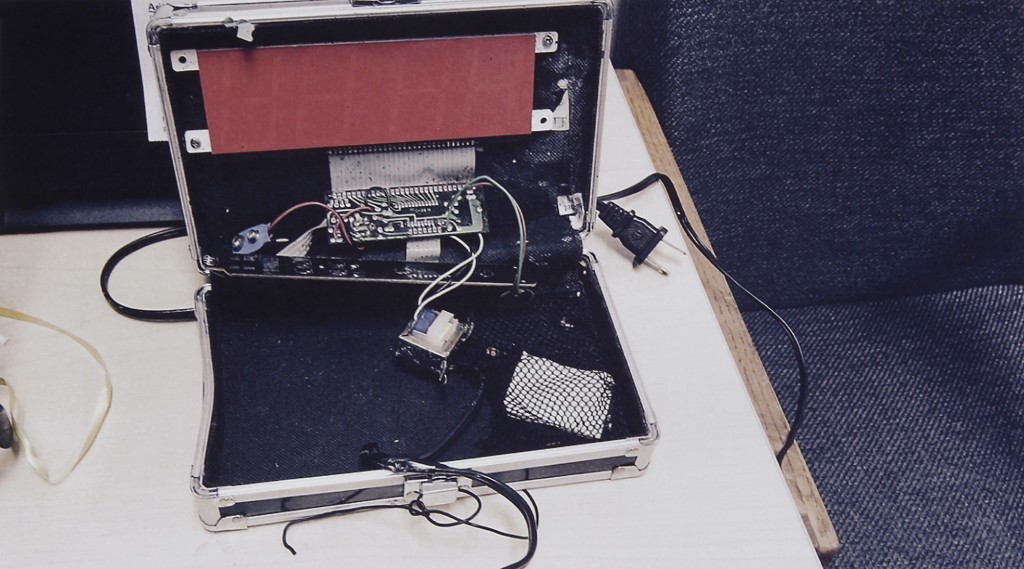

That is a picture of a homemade clock that Ahmed Mohamed took to school to show his teachers. This turned out to have been a bad idea, as The Dallas Morning News reports:

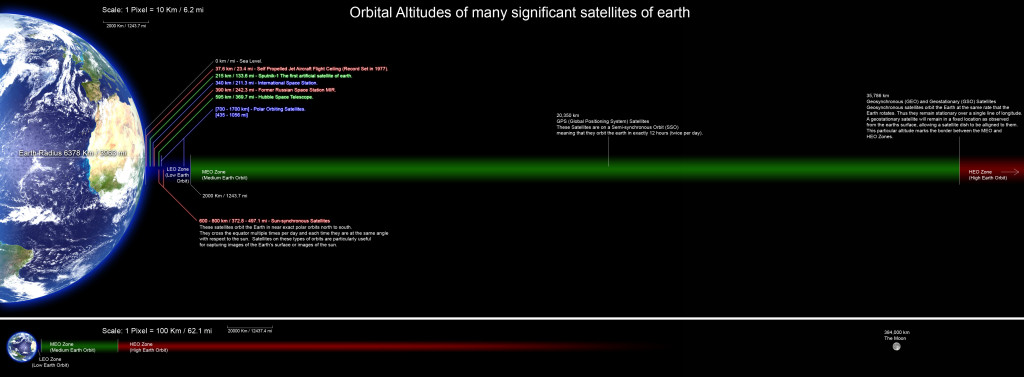

Ahmed’s clock was hardly his most elaborate creation. He said he threw it together in about 20 minutes before bedtime on Sunday: a circuit board and power supply wired to a digital display, all strapped inside a case with a tiger hologram on the front.

He showed it to his engineering teacher first thing Monday morning and didn’t get quite the reaction he’d hoped for.

“He was like, ‘That’s really nice,’” Ahmed said. “‘I would advise you not to show any other teachers.’”

He kept the clock inside his school bag in English class, but the teacher complained when the alarm beeped in the middle of a lesson. Ahmed brought his invention up to show her afterward.

“She was like, it looks like a bomb,” he said.

“I told her, ‘It doesn’t look like a bomb to me.’”

The teacher kept the clock. When the principal and a police officer pulled Ahmed out of sixth period, he suspected he wouldn’t get it back.

He suspected that he wasn’t going to get it back, but he probably didn’t expect to get interrogated, intimidated by his principle, and then led away in handcuffs. For making a clock.

Since then, some semblance of sanity has apparently returned and the police say that Ahmed will not be facing any charges. That’s good. On the other hand, they are standing by their initial decision. That’s hardly surprising. It will be a cold day in Hell before a police force in this country (or any country) voluntarily acknowledges that they made a mistake. That’s how authoritative institutions work: they preserve their own power at any cost.

At a press conference today, a police spokesperson claimed that the device was both “a hoax bomb” and a “naive accident.” That position makes no sense. A hoax is a deliberate attempt to deceive people. An accident is not. Which is it? Given that Ahmed’s behavior it is obvious to any sane human being that it’s really neither. It’s just a talented kid who wanted to show something cool that he’d made to his teachers.

The outrage factor on this one is high, and–while I admit I’m seething–I’d like to step back from just shouting at stupid people doing stupid things because they are stupid. That’s not productive. What might be instructive is this article from Gawker: 7 Kids Not Named Mohamed Who Brought Homemade Clocks to School And Didn’t Get Arrested. So: Let’s not pretend that Ahmed’s name is not irrelevant here. Obviously it is.

Although charges were never filed by the police, Ahmed was suspended for three days by his principle. For what? According to US Today:

The principal referred questions to the district, which released a statement: “We always ask our students and staff to immediately report if they observe any suspicious items and/or suspicious behavior.”

So. “If you see something, say something.” The problem with vigilance is that if you don’t know what to be vigilant for you’re not actually being vigilant. You’re being paranoid. His English teacher was scared. What does his English teacher know about explosives? Or electronics? Not much. The police were scared. One said, “It looks like a movie bomb to me.” Clearly we’re dealing with professionals here.

I know I’m veering into sarcasm again, but there’s a sincere point I want to make. Prejudice obviously played a role in this case, and prejudice obviously plays a role in a great deal of the injustice that happens in our world. But prejudice alone doesn’t explain everything. What happened in Irving took prejudice but also ignorance and especially fear. Fear and ignorance are catalysts that exacerbate underlying prejudices.

If you want to make the world more just and more fair, don’t exclusively oppose prejudice. Prejudice is hardcoded into human nature at a pretty low level. We generalize (make groups) and we infer (draw conclusions about general categories based on individual examples). Neither generalization nor inference are going away, nor should they; we need them to think. But as long as they are around, trying to train people to not apply generalization or inference in certain cases is fighting an uphill battle. It’s worth fighting, but maybe we don’t need to put all our eggs in that basket.

I’ve written about fear a lot recently, once in the specific context of refugees and migrants and more generally when it comes to security and safety. The message in both cases is pretty similar. First, we need to be willing to assess risks rationally to the best of our abilities. Second, doing the right thing means confronting fear. There is no progress without a general willingness to take risks. They come down to the same thing: don’t let fear be in control.

There’s a saying that all motivations in life boil down to two things: love and fear. Or, less poetically but more accurately: attraction and aversion. Even the tiniest microorganism has to make that decision constantly: do I approach (a potential food source) or avoid (a potential predator)? As a general rule, I think life goes better when we let love lead the way. When we are motivated by what we want to go towards rather than what we’re trying to get away from. When we strive towards what we want to make happen by rather than what we want to prevent.

So, in addition to our conversations about prejudice, it might help to also have a conversation about basic bravery. About setting aside our worship of fear. When 9/11 happened, it made the country better in a lot of ways: it brought us closer together (for a while, at least), it focused our priorities on what really matters (for a while, at least), and it reminded us of what real heroism and sacrifice look like (we seem to be doing a better job of remembering that one). But it also had some dark effects, and those effects are lingering stubbornly. Chief among them: it taught us a new kind of fear. That fear has already convinced us to trade away an awful lot of money, an awful lot of lives, an awful lot of our principles, an an awful lot of our civil liberties. We’ve spent an awful lot of time–individually and as a nation–being motivated by aversion. By fear. Maybe it’s time to change the motivation.

They say that we should never forget 9/11, but I think that depends on exactly what you’re trying to enshrine in memory. If you’re talking about the sacrifices and bravery of first responders and the folks on Flight 93, then of course we all agree. But maybe there’s more we should remember, like what it was to be an American on 9/10, before our national psyche was scarred. I think there were some things we did better then. Like not overreacting to some poor geek and his harmless hobby just because his name is Ahmed. We can’t just turn the clock back. We can’t literally forget, and we shouldn’t. But if we can get back even a little bit of that openness and confidence it will mean something. Because this time it we will be choosing openness and confidence and bravery in spite of fear rather than merely stumbling into them.

Let’s recognize prejudice for what it is and fight it. Let’s do the same with fear.

There’s a thought-provoking article in the

There’s a thought-provoking article in the