In the past couple of years, I’ve read several books that deal with the origins of human society: Frans de Waal’s The Bonobo and the Atheist, Matt Ridley’s The Origins of Virtue, Francis Fukuyama’s Origins of Political Order, and Yuval Harari’s Sapiens are just a few examples.

One of the common themes in these books was that the leap from the band-level socities (usually capped at about 150 members) to tribal societies depended on the creation of mythological common ancestors. Tribal societies were successful because they could scale up in times of crisis. The bigger the crises, the more the individual groups would need to group together, so the farther back in time they would look to a common ancestor. A small crisis might entail a couple of tribes who were descended from a common, living grandfather. A medium crisis might require going back a few more generations to a long-dead (but possibly historical) great-great-grandfather. And a really large crisis might require going back even farther to mythical ancestors who may or may not have ever lived. The point was that–because they could always create an ancestor further back in time–tribal societies had truly immense ability to scale up (at least in the short term when faced with an external threat.)

Now, I’m very far from the first person to call modern American political discourse tribal. Basically everyone can see that our society is increasingly fracturing into diverse, ideologically pure and rigid social groups for whom politics is much more about creating and maintaining in-group solidarity than honest political differences.

If you’d like a recap, here’s a long but very awesome article about this: I Can Tolerate Anything Except the Outgroup. In the article, Scott Alexander[ref]a pseudonym[/ref] posits three main tribes in American society: red (conservative), blue (liberal) and gray (techno-libertarian). These are the top-level tribes, but each one is composed of a dense connection of sub-tribes, each smaller and more specific than the level above. For example, the gun-rights crowd is a sub-group in the red-tribe, and the open carry movement is a sub-group of that group.

Now, if you’d asked me last week, I would not have made any serious connection between the development of tribal societies in human prehistory and the rise of tribal politics in the United States. For the most part, the reason people make this analogy is that “tribal” has pretty negative connotations (e.g. insularity, xenophobia, and irrationality) that pretty closely match the behavior we’re seeing in American political society. So, a convenient connection but also a pretty superficial one.

But now I’m starting to think that the connection is actually much deeper than that.

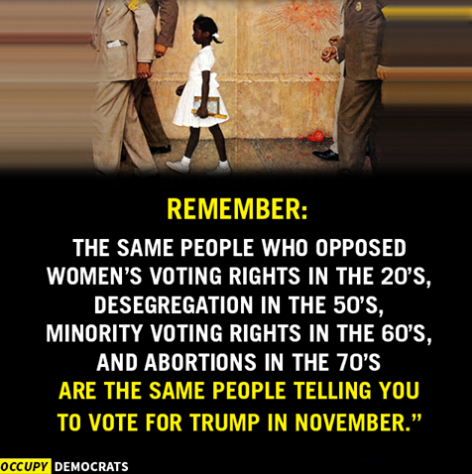

Take a look at this image (one that a Facebook friend posted recently):

Now, it’s got all the hallmarks of really obnoxious political memes, right down to the sloppy grammar. I’m looking at you, random lonely quotation marks.[ref]Is there a rulebook somewhere that says you have to include grammar mistakes in a successful meme? That was a joke at first. Then I realized that the folks replying to complain about the grammar would actually boost the meme’s stats in Facebook’s algorithms, so now I’m sad because I realize that it’s not a joke after all.[/ref]

Now, according to this meme “the same people” were fighting against women’s rights in the 1920s, against equal rights for blacks in the 1950s and 1960s, against women’s rights again in the 1970s, and are now supporting Trump in the 2010s. So, who are these mysteriously long-lived people? Who are all those folks showing up in Trump rallies today that were waving anti-enfranchisement posters nearly 100 years ago? Obviously: nobody. Because humans don’t live that long.

Then what does “the same people” refer to? Perhaps there’s an ideology that’s around today that’s been around for 100 years, and so it’s not the individual human beings but the ideology that is the problem. This is also unlikely, however. Not only do ideologies change and mutate over time, but the reality is that (to pick a couple of issues), most of the women’s rights activists of the 1920s were extremely pro-life and would have been campaigning against abortion in the 1970s. Donald Trump, meanwhile, has been pro-choice almost his whole life, only switched to pro-life recently, and didn’t even do a half-way decent job of being convincing about it. So–even if there were such a thing as ideological philosophies that were consistent over time frames of a century or more–there isn’t one that aligns with these issues.

So what’s going on?

In simple terms, Occupy Democrats is creating a mythological ideology in exactly the same way that ancient tribal societies created mythological ancestors. The idea of Romulus created a bond between Romans who might otherwise come from different families, neighborhoods, or tribes. The bond was real, even if the Romulus was not. In the same way, the blue tribe is inventing a narrative of centuries’ of struggle for equal rights that always had a “good side” for them to claim membership in. Of course that’s a comforting belief, but the most important function that it plays is to unify the various sub-groups within the blue tribe who otherwise might fall into internal squabbles.

So, the analogy to tribes goes much deeper than I first thought.

And of course, this isn’t something just the blue tribe gets up to. All tribes do it. They invent common ancestors or (in our ideological time) common ancestral ideologies. The red tribe has actually been at it far, far longer than the blue tribe, but they choose a different narrative. Instead of a battle over equal rights, the red tribe has a battle to preserve the ideals of the American Constitution, and so the Founding Fathers function as the mythological common ancestors and the Constitution as the mythological common ideology of the red tribe.[ref]Obviously the Founding Fathers are not mythological in the sense of being made-up. That’s not the point. They are mythological in the sense of being a holy narrative that contains symbolic truths which bind together a group of people who share reverence for the narrative.[/ref]

Now, if you’ve got any advice on how to get people to stop posting this kind of tribalistic nonsense, I’d love to hear it. I’m begging my friends not to do it anymore–because it makes me hate being on Facebook and is bad for the country–but the worst part is that the kind of people who post this sort of thing (on the left or the right) are precisely the kind of people who can’t conceive of any way in which they could be doing any harm. After all, they’re just telling it like it is, right?

Most people are in favor of renewable energy such as wind and solar, yet many supporters tend to look at natural gas with disdain.[ref]Arguably due to the means of its extraction (fracking). For example, there’s been

Most people are in favor of renewable energy such as wind and solar, yet many supporters tend to look at natural gas with disdain.[ref]Arguably due to the means of its extraction (fracking). For example, there’s been