You might not have heard, but the sci-fi community is currently embroiled in a civil war. Then again, you might actually have heard. Things have gotten so bad that the story hit both USA Today and then the Washington Post this week. I want to share the story, and my perspective on it, for two reasons. First: I love sci-fi. But second, and more relevant to a broader audience, the way that political partisanship has torn the sci-fi community apart is pretty good case study of how partisanship damages the fabric of larger communities.

The Literature of Ideas

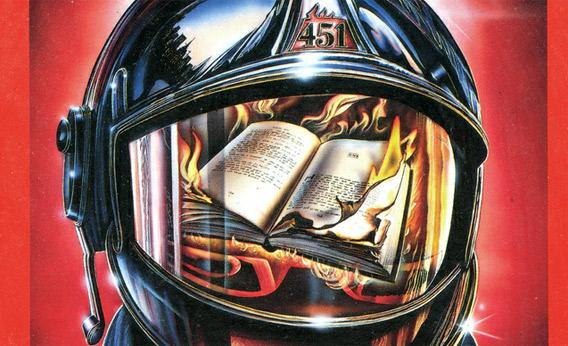

I love science fiction because it is, as Pamela Sargent called it, “the literature of ideas.” For me the animating spirit of sci-fi is the spirit of inquiry. The genre has less to do with with outer trappings of spaceships or robots and more to do with the simple question: “What if?” This has been true since some of the earliest science fiction works, like Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. Dr. Frankenstein’s futuristic technology for reanimating corpses is central to the plot and intrinsically interesting, but it’s there in order to support moral questions about the duty of the creator to the created.[ref]You can tell a lot about the genre of sci-fi just by noting that the full title of the book is Frankenstein, or The Modern Prometheus.[/ref] That setup, envisioning alternate technology in order to frame questions that couldn’t be examined so clearly without the imaginary technology, is the essence of science fiction. That is the sense in which it is truly the literature of ideas.

I understand that Frankenstein isn’t necessarily the first book that people think of when they think of science fiction and that my definition isn’t universal. But it’s not just my random personal opinion, either. In addition to Sargent, sci-fi legend Ursula K. Le Guin recently told the Smithsonian Magazine (speaking about the impact of science fiction on real-world society), “The future is a safe, sterile laboratory for trying out ideas in, a means of thinking about reality, a method.” That method is exactly what I fell in love with.

The first science fiction that I ever read was 1950’s era series Tom Swift, Jr. Even though it was mostly ghost-written fluff for little kids, it couldn’t help but convey a sense of the importance of ideas. Ideas matter. Ideas change how see the world, and can therefore change what we make of the world. Science fiction isn’t about predicting the future. It is, in a small but real way, about shaping the future.

Politics in Sci-Fi

Of course you can’t get all poetic about the literature of ideas without expecting to find a good deal of politics along for the ride. The Tom Swift, Jr. novels all conveyed a surplus of good ole American patriotism in the best tradition of 1950s Cold War sentiment. Meanwhile, Le Guin’s The Left Hand of Darkness is an inquiry into the social role of gender by examining a hermaphroditic alien race while The Dispossessed

is an inquiry into the social role of gender by examining a hermaphroditic alien race while The Dispossessed explores the tension between human nature and left-wing, Utopian political ideals.

explores the tension between human nature and left-wing, Utopian political ideals.

Part of what I love about the genre is that it explicitly talks about all that stuff that you’re not supposed to bring up in polite company: politics, religion, and morality. Sci-fi has always been full of wildly divergent ideas for better and for worse. Mostly for better, in my experience. When writers care more about their craft–about engaging the audience and telling a good story–this usually forces them to be at least a little nuanced and careful in their politics. Most of us don’t like preachy characters or message fiction, even when we might largely agree with them. That’s why I’ve always viewed Heinlein’s writings with a mixture of admiration and tolerant patience, sort of like a crazy uncle who can be forgiven his occasional political ranting because he otherwise tells a good story.[ref]And, just to be clear, I like a lot of what Heinlein has to say about politics, as in The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress .[/ref] A lot of my favorite authors (Le Guin, but also C. J. Cherryh and Lois McMaster Bujold) are folks who, I’m pretty sure, have politics that are far, far away from mine. I love their stuff anyway. And for writers who are closer to my world view, like Larry Correia, there’s no guarantee that I will like what they write just because I agree with some of their political views.[ref]I loved Hard Magic: Book I of the Grimnoir Chronicles

.[/ref] A lot of my favorite authors (Le Guin, but also C. J. Cherryh and Lois McMaster Bujold) are folks who, I’m pretty sure, have politics that are far, far away from mine. I love their stuff anyway. And for writers who are closer to my world view, like Larry Correia, there’s no guarantee that I will like what they write just because I agree with some of their political views.[ref]I loved Hard Magic: Book I of the Grimnoir Chronicles and the rest of the Grimnoir series. I didn’t really get into Monster Hunter International (Monster Hunters International).[/ref]

and the rest of the Grimnoir series. I didn’t really get into Monster Hunter International (Monster Hunters International).[/ref]

I have no idea how right-wing and left-wing authors got along in decades past, but as far as I can tell they managed just fine. I’m basing this on the fact that some of the old guard have reacted with annoyance and disdain to the politicizing of the current crop of sci-fi authors, but we’ll get back to that in a bit. Meanwhile, the audience had no trouble picking and choosing from a variety of authors. If you wanted to find authors who agreed with your politics, you probably could. Traditional, conservative folks like me might have to work a little harder to find a common voice, but they were out there. And, most importantly, you probably had no real strong desire for political conformity. The audience was perfectly happy to go along with a wide-range of political, religious, and ethical viewpoints. It was part of the experience, and usually a beneficial one all around.

The Political Polarization of Sci-Fi

In recent years, this happy little equilibrium has collapsed. It’s impossible for me to know if the reason is technological or political, but it’s probably both. The technological changes include social media and self-publishing. Social media makes it easier for sci-fi authors to interact directly with their fans and also to interact with each other in impersonal and public ways. Self-publishing forces more and more authors to do just that. It’s called platform building, and the idea is that authors have an obligation to get out there and build a brand name. This is especially true for self-published authors, but even traditionally published authors feel the pressure to get out there and be as visible as possible to boost their sales.[ref]I’m not an author, so I’m basing this on what I’ve heard from various traditional and self-published authors whose blogs I follow.[/ref]

It is absolutely not a coincidence that two of the central figures in the current civil war–John Scalzi and Larry Correia–are both relative newcomers to the genre and both at the forefront of those respective technologies. For his part, John Scalzi runs the incredibly popular blog The Whatever, which he’s maintained since 1998 (before “blogging” was even a thing). The most prominent recurring feature on The Whatever is a segment called “The Big Idea” in which Scalzi turns over the mic to authors with a book coming out to discuss and promote their work. Scalzi’s blog promotes his own stuff, too, of course. He mentions his Hugo-eligible books and stories whenever nomination time comes around and announces new projects, too, but he also uses his platform to help out others. It is a very big platform by now. Scalzi also self-published his first sci-fi novel, Old Man’s War before it was bought by Tor. Scalzi is an outspoken liberal who penned the incredibly famous article about white-male privilege: Straight White Male: The Easiest Difficulty Setting There Is.

before it was bought by Tor. Scalzi is an outspoken liberal who penned the incredibly famous article about white-male privilege: Straight White Male: The Easiest Difficulty Setting There Is.

On the other side we’ve got Larry Correia. Whereas Scalzi has been a professional writer throughout his entire career (he did film reviews, non-fiction, and corporate writing before he broke into sci-fi in 2005), Correia is an even more recent entrant to the field of professional writing. His breakout hit, Monster Hunter International , was self-published in 2007 before it was picked up by Baen and republished in 2009. He currently has 9 sci-fi books in print (which is about the same as Scalzi, I think) and runs his own blog incredibly popular blog called Monster Hunter Nation. Where Scalzi is an outspoken liberal, Correia is a Mormon and proud gun-nut with generally conservative views.[ref]That makes Correia a lot closer to me on the political and religious spectrums, in case you haven’t been reading this blog very much.[/ref]

, was self-published in 2007 before it was picked up by Baen and republished in 2009. He currently has 9 sci-fi books in print (which is about the same as Scalzi, I think) and runs his own blog incredibly popular blog called Monster Hunter Nation. Where Scalzi is an outspoken liberal, Correia is a Mormon and proud gun-nut with generally conservative views.[ref]That makes Correia a lot closer to me on the political and religious spectrums, in case you haven’t been reading this blog very much.[/ref]

Both of these gentleman have a lot of readers and fans, both of their books and also of their blogs. As you can imagine, this is a recipe for trouble. In the old days, neither Correia nor Scalzi would have been so well known for their political views because for the most part the sci-fi audience had to guess at politics from what the fiction that author published. If they even thought about it at all. Which, unless the book appeared to take an overt stance, they probably didn’t. Now there is more awareness but, unfortunately, there are also sides. The blogs are not just a source of information, but also a virtual space for like-minded fans to congregate. It’s no surprise that Scalzi’s blog is stuffed to the gills with commenters who generally agree with his views and applaud his willingness to write about them publicly, and the same goes for Correia, although perhaps less-so since Correia takes a more hands-off approach to comment moderation. It’s hard to imagine that this homogeneity doesn’t radicalize the views of Scalzi and Correia at least a little bit simply because human nature is what it is, and it definitely radicalizes the communities themselves. When contrarians come around to pick a fight,they are seen not just as someone who disagrees, but as representative of the other tribe. And then, last but not least, there’s the fact that these politicized leaders of politicized tribes can shout at each other in public. Thanks to social media, authors not only interact with their fans more (and in public) but also with each other more (and in public).

None of this is anybody’s fault, really. There are no villains thus far. It’s just the way things are. Technology has consequences for society, and one of the consequences of social media in all its many forms is to make it easier for people to sort themselves into like-minded groups, whether that’s their intent or not. This is why the civil war in sci-fi is perhaps just a smaller example of the larger trends taking place across our society as a whole.

Of course, it’s also possible that Scalzi, Correia, or both are just more politicized than the Old Guard. (I’ve noticed, for example, that a much more experienced writer like C. J. Cherryh definitely has her opinions, but has so far kept completely out of internecine combat, even when it touches on issues that she personally cares about.) I’m not as interested in the theory that newer writers are just more political for two reasons. First: I just don’t think there’s any way to judge. Second: even if they are, you might still wonder if there’s some reason for that fact. In other words: it might still come back to a consequence of coming into your own as a professional writer in an era of social networking and platform building. In any case, I’m sticking with a technology-based explanation of political radicalization in the sci-fi community for this post.

What Hath Partisanship Wrought?

So what is actually going on? Well, if you ask the liberals, they are just trying to make the sci-fi community safe for minorities by chasing out hatemongers and bigots. If you ask the conservatives, they are trying to keep the sci-fi community safe for free-thinkers by resisting political correctness. The sad irony is that a central strategy of the conservatives is to say intentionally provocative things (you can’t keep a right if you don’t exercise it) and a chief strategy of the liberals is to interpret whatever conservatives say in the worst possible light (to validate their claim that the racists, sexists, etc. have got to go). It looks almost as though the two sides just decided to have the biggest, nastiest, most convoluted fight they could possible have, and came up with the perfect strategy to escalate and perpetuate it. Call it cooperation or call it co-dependency; it’s ugly by any name. The saddest part? Both sides contain a mix of decent people who really think they are trying to do the right thing, people who seem to have some serious issues unrelated to politics, and plain old trolls. Good luck sorting that out.

In practical terms, there’s an ongoing feud at the SFWA (that’s the professional organization for sci-fi writers, artists, and editors) that culminated in a particularly controversial conservative named Theodore Beale (who writes under Vox Day) being formally ejected from the organization. You can read a self-declared liberal-slanted recap of that mess here. Lest that make you think that the conservatives were being unreasonable, the liberals worked hard to show they could be just as insane when they went bananas over the announcement that Jonathan Ross was going to host the 2014 Hugo awards. Jonathan Ross, a British comedian who is married to Hugo-winner Jane Goldman, had no idea that he was walking into a minefield because (like most of humanity) he didn’t know about the ongoing SFWA feuds. So when a couple of liberals protested (based on no evidence at all that I can see) that he would make fat-jokes and this would make the ceremony hostile for overweight people, he didn’t handle their concerns with kid gloves. The spat blew up on Twitter with sci-fi author Seanan McGuire getting into a fight with Ross’s daughter who tried to defend her dad by saying: “I’m Jonathan’s overweight daughter and I assure you that there are few men more kind & sensitive towards women’s body issues.” Yeah, it was that ugly. Understandably, Ross said “the Hell with this”[ref]Not an actual quote, so far as I know/[/ref] and backed out. Liberals, as a general rule, celebrated their victory although there were exceptions. Neil Gaiman, for example, said that he was:

seriously disappointed in the people, some of whom I know and respect, who stirred other people up to send invective, obscenities and hatred Jonathan’s way over Twitter (and the moment you put someone’s @name into a tweet, you are sending it to that person), much of it the kind of stuff that they seemed to be worried that he might possibly say at the Hugos, unaware of the ironies involved.

But things really blew up when the Hugo nominations were announced on April 19. It didn’t take long for folks to notice that there were a lot of unexpected names on the list, and that those names corresponded to a slate of nominations from conservative-leaning authors Larry Correia had promoted on his own site starting back on March 25. Worst of all? The list included a novellete by none other than Vox Day / Theodore Beale. Scalzi responded immediately, although in stark contrast to his polemics during the controversy so far he took a moderate, calming approach, headlining his piece: No, The Hugo Nominations Were Not Rigged. Other than throwing a bone to his political allies, dog-whistle style[ref]It was a smart move. He pacified his allies by giving them a platform, but refrained from further escalating the fight himself.[/ref], Scalzi has essentially gone radio dark on politics since then.[ref]There was one exception, but by ignoring the Hugo controversy itself it continued the pattern of expressing general support for the liberal side of this war without actually joining in.[/ref] My theory is that Scalzi is smart enough to realize that the fight is now getting to a point where it’s going to start threatening the genre as a whole. Or, he might just be biding time to unleash after the Hugos, which is what others have explicitly stated that they are doing[ref]I’m afraid I’ve forgotten the name and lost the link of the particular author who stated this, but it was someone who is also up for a Hugo this year. I’ll try to recover it.[/ref]. Meanwhile others, like Tor author John C. Wright (who is friends with Correia and other conservatives) isn’t waiting. He publicly resigned from SFWA in an open letter.[ref]Notably, however, he did not sever his relationship with Tor.[/ref]

So now the sci-fi community has officially lost its mind. What bothers me the most, however, is to see that even the publishers are starting to get involved. John Scalzi’s editor and friend Patrick Nielsen Hayden has been a loud voice criticizing the conservative side (you have to go into the comments to find it, try #501 or #502). He is also senior editor at Tor, which recently published a controversial article arguing that sci-fi writers should stop using binary gender in their books.[ref]I’m not exaggerating. The first line is: “I want an end to the default of binary gender in science fiction stories.”[/ref] Tor is also where Scalzi publishes. Meanwhile Baen, where Correia lives, is cultivating it’s reputation as the place where conservatives can flee oppressive liberal Manhattan editors. This sentiment is reflected by Baen author Brad Torgersen along with Larry Correia himself. Meanwhile Baen editor Toni Weisskopf (guest-posting at Baen author and conservative Sarah Hoyt’s website) gives the impression that Baen as a corporate entity is at least marginally OK with their status as political refuge.

Let’s recap: back in the day authors put their politics in the books. Fans, editors, and publishing houses, as far as I can tell, didn’t have any stark partisan divides. Today, authors put their politics out there in blog posts and tweets, which become rallying cries for groups of like-minded fans. Then the fans and the authors get into fights with each other over politics. And, because the community is so small, these fights get personal and nasty very quickly.

Where Does It End?

I don’t want politics out of sci-fi books, but I do wish we could get politics out of the sci-fi publishing world. I’m not really sure if we can just roll the clock back to where things were before. I suspect not, and that makes me sad. On the other hand, this is one of those situations where markets and profit-seeking tend to make people behave more decently rather than less. I suspect money, consciously or unconsciously, has a lot to do with Scalzi’s sudden moderation. And that it had to do with Wright quitting the SFWA but not Tor. Baen publishes Lois McMaster Bujold (who I suspect is not conservative) and Tor publishes David Weber (who most definitely is), and these refugees give hope that we can stop things from sliding into full-on, open warfare with the publishers as intentional ideological mouthpieces.

My perspective is one of both fan and hopeful author. I hope that when I’m ready to start submitting my stories, probably in a couple of years, sci-fi will still boast the free-wheeling intellectual, religious, and political diversity that I’ve always loved. Look, I know that as a conservative I will always be viewed with faint suspicion and find myself the odd-man-out, but part of being a conservative is being willing to deal with bad luck (like finding yourself in a minority position) without complaining. I’m willing to accommodate myself to that reality. All I want is a chance to participate in one, big, giant conversation. I don’t want it to be my turn to try writing and find that instead of this chaotic tapestry of audience and texts I’ve got a regimented set of ideologically homogeneous boxes, and that I’ve got to pick just one.

Sci fi, as the literature of ideas, cannot survive under those conditions.

Disclaimer (added as an update)

I mentioned a lot of individuals by name in this post. I do not know any of them personally, nor do I have any inside information. When it comes to my guesses as to the motivations of named individuals, I’ve tried to be generous and conservative (not in the political sense) but I might still get it wrong. In any case: talking about people individually is not the point. It’s just there to provide the story, as best I understand it. The overall trend of political polarization is unmistakable and is based, as I suggest, primarily on general technological trends rather than the actions of any particular author or editor. I really do think there are good and decent people on both sides of the political divide here. And I really think there are people who have behaved very poorly, but I have not focused on that in this post.