I want to write a post about that controversial rape scene from last week’s episode of Game of Thrones, about why I don’t watch Game of Thrones, and about the ethics of creating and consuming entertainment and art, but first I need to explain the structure of reality.[ref]That’s a little but of humor there, folks. But also I’m serious.[/ref]

Naïve Realism

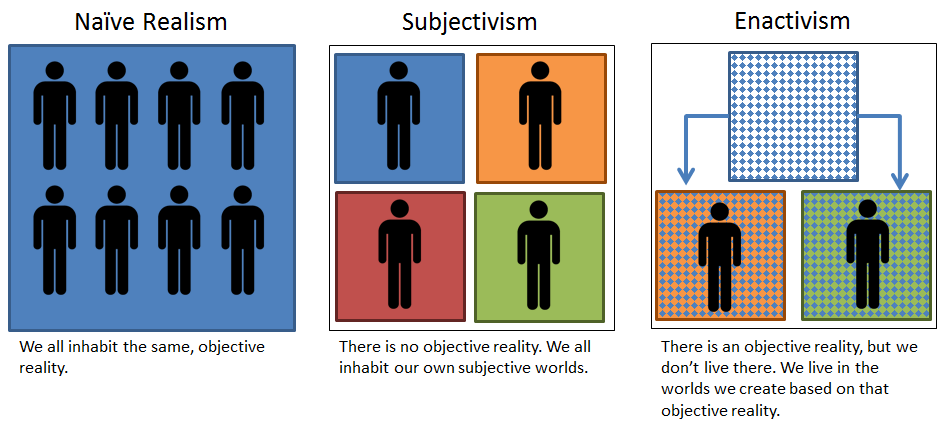

Realism is the idea that the external world is objectively there, whether we observe it or not. There are lots of different kinds of realism, but the default view (especially among folks who don’t go out of their way to study this) is naïve realism. That’s the idea that the world is out there and that we perceive it directly (and more or less reliably) through our senses. According to this view, objective reality exists, and we all live in it.

Subjectivism

The alternative to realism is idealism. These days, and throughout much of history, idealism has been a minority view but an important one. Descartes kicked off modern Western philosophy with his Meditations, the most famous line of which is cogito ergo sum, or “I think, therefore I am.” That’s a fundamentally idealist perspective, because it starts with the mind first, independent of any observation about the external, physical world.

The best way to think about the relationship between idealism and realism is this. According to realism we can all be sure of the fact that we have brains, but the question of whether or not we have minds is an open one. According to idealism, we can all be sure of the fact that we have minds, but the question of whether or not we have brains is an open one.

Subjectivism is a particularly extreme form of idealism that, as far as I can tell, is the most popular alternative to naïve realism among non-philosophers. Subjectivism is the idea that all truth depends on our perception. In that view, there is no objective reality. We all live in our own little subjective realities where things are true for us that might not be true for anyone else.

Problems with Naïve Realism and Subjectivism

The simplest argument for realism is stubbing your toe. No matter how much you didn’t perceive that the doorframe was going to hit your foot right there, it did. And then it hurts. Clearly objective, physical reality doesn’t really wait around for you to perceive it before it imposes consequences on your perception.

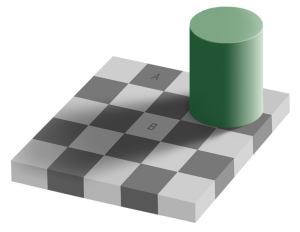

So there is strong argument for objectivity, but naïve realism is more than just objectivity. It also asserts that we directly perceive the world around us through our senses.

The counterexample to that is the existence of optical illusions. It’s not the simple fact that our senses can be mistaken that causes the problem for naïve realism, however, it’s the way that optical illusions hijack the unconscious processes that we use to construct an internal reality from raw sense data. This proves that there isn’t a simple, direct correspondence between what’s out there, what we perceive as sense data, and what we then perceive as being out there.

The situation is worse when it comes to subjectivism because the concept is obviously incoherent. For a full treatment, I recommend Thomas Nagel’s The Last Word, but here’s one quick example of why subjectivism makes no sense. Subjectivism says that no claims about reality can be objectively true or false, but subjectivism itself is an objective claim about reality. That doesn’t prove it’s false. It just proves that it’s incoherent. No sane person can rationally believe subjectivism.

So why is it popular? Well some things (like taste) really are subjective. More importantly, however, subjectivism is what some people run to because it seems like the only alternative that captures the idea that perspective really matters. You and I may look at the same situation and come to different conclusions, and we might both be right. This doesn’t actually require subjectivism (you can have different viewpoints and conditional / provisional truth claims within an objective framework), but it’s close enough to confuse lots of folks.

Enactivism

Every now and then I come up with some theory or other, and I tinker with it more and more over the months and years and when I know that it’s a really good, solid theory that’s when I can be confident that it already exists on Wikipedia. Enactivism is one of those concepts. From the entry:

Enactivism argues that cognition depends on a dynamic interaction between the cognitive agent and its environment: “Organisms do not passively receive information from their environments, which they then translate into internal representations. Natural cognitive systems…participate in the generation of meaning …engaging in transformational and not merely informational interactions: they enact a world.”

In this sense, enactivism is a fusion of naïve realism and subjectivism. It starts with the idea that objective reality is really out there. But we don’t perceive it directly. Instead, we take the sense data that is there as raw material, and we use that raw material to build our own private, internal models of the world. Because we’re all starting with the same objective reality, our individual constructed realities have lots of points of contact. This is one reason why communication is possible: because we’re often talking about the same basic reality.

Welcome to Your Matrix

Part of our constructed reality is a model of objective reality. Here, I’m thinking about everything relating to physics. We use our senses to identify objects, how far away they are, how big they are, what direction they’re moving in, etc. Part of our constructed reality appears to consist of patterns of organization that just are. Like math. 2+2 =4 for everyone, even though the number two is not a physical thing. In this sense our constructed realities are less than objective reality, which is the real thing. We only see some of what is out there, we sometimes misidentify what we do see, and we imperfectly apply rules of logic and math.

But part of our constructed reality is more than objective reality. The most essential concept here is narrative. Objective reality is just stuff that happens. There isn’t, outside of the rules of physics, a why. There isn’t meaning or purpose. That stuff exists in our constructed reality. Now, maybe it also exists in objective reality (because God says so, or for some other reason), but we can’t really be sure of that.

Shared Reality

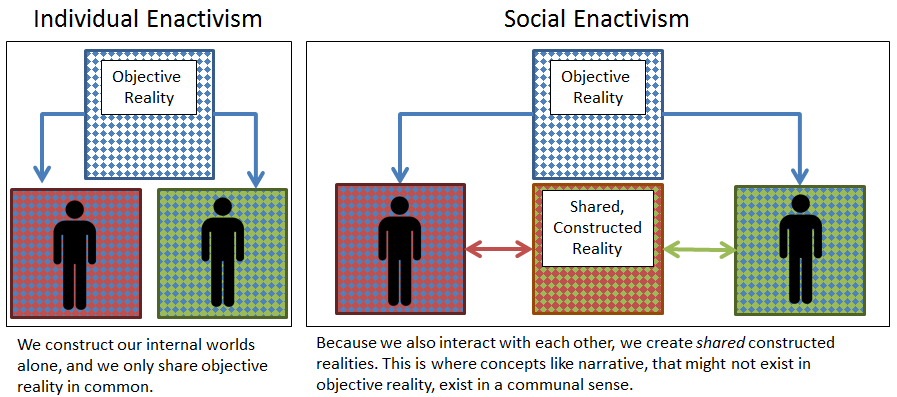

There’s one last twist that I’ll put on enactivism before I get back to Game of Thrones (no, I hadn’t forgotten). That’s the idea of shared constructed realities.

Because we’re constantly interacting with each other, our individual realities are permeable. We have our own narratives, in which we are always the hero of our own story, but we share these narratives with other folks who agree or disagree with them. In addition, when we create things we are always cooperating in the creation of a shared, constructed reality. This is true even for individuals who do their creative work alone. Think about J. K. Rowling, writing her stories before anybody else had read them. At that point, they were strictly within her own reality. But once the world read them, then we became participants with J. K. Rowling in creating this shared reality.

Did the deaths of Sirius, or of Dumbledore, or of Dobby affect you? They affected me. Dobby’s, in particular, brought me to tears. That doesn’t mean that I was confused and thought that Dobby was out there in objective reality or that magic was real, but it does mean that there was as a sense in which at a deep, subconscious level, J. K. Rowling’s creation had become real to me.

For me it’s an open question if some narratives are objectively true. It may be possible that the shared, constructed reality is just our attempt to recreate objective reality, and that we can be right or wrong about narratives in the same way that we can be right or wrong about guessing size or distance or speed. But, practically speaking, there is a difference between objective reality (which can be quantified and objectively evaluated) and our shared, constructed realities (which cannot).

The Ethics of Sub-Creation

According to what I’ve read about J. R. R. Tolkien, he referred to world-building as “sub-creation.”

‘Sub-creation’ was also used by J.R.R. Tolkien to refer the to process of world-building and creating myths. In this context, a human author is a ‘little maker’ creating his own world as a sub-set within God’s primary creation. Like the beings of Middle-earth, Tolkien saw his works as mere emulation of the true creation performed by God.(Tolkien Gateway)

This is an extremely powerful for me, because I’ve always believed in a kind of grand universal theory of everything (only for metaphysics, rather than physics) that would somehow unify the True, the Good, and the Beautiful. On a more practical level, it provides a window into the ethics of sub-creation, which is the ethics of artistic creativity.

I know I’m going to lose a ton of people who bridle at the idea of imposing laws or commands on artistic expression (on the one hand) and who are horrified by the history of attempts to subvert artistic expression to propaganda for someone’s idea of right and wrong (on the other). These are serious concerns, but I do not think they apply to what I have in mind.

First, when it comes to rules and laws, I think we can all appreciate that a greater understanding of physical laws allows us to be more creative rather than less. This applies not only to what our engineers can build, but also to what our scientists and philosophers can imagine. I am not by any means suggesting that I could come up with the “right” rules for how to do art, or some objective metric for deciding what piece of art has more merit than another. It is not only foolish but vulgar to attempt to rank the Beauty of Mozart’s Requiem vs. that of Allegri’s Miserere, in my mind.[ref]I have no musical expertise. These are just pieces that mean a lot to me, personally. I have no idea what critics think of their relative merits.[/ref] But it isn’t vulgar or futile to wonder if there aren’t common principles—like symmetry and transcendence and struggle—which might animate both and help make each great.

Second, the grand unifying theory of everything is outside our grasp so, if we are appropriately humble, the danger of propagandizing is low. Propaganda is for people who already know what they want others to think, but someone who is searching for truth out there has no such agenda to sate and no pretext of certainty with which to sate it.

What I have in mind, by contrast, is a kind of unification of three activities that people might not ordinarily see as connected: faith, artistic creation, and artistic consumption.

Let me start out by illustrating that, because we have a wide range of freedom in constructing our realities, there is room for this to be a meaningfully moral activity. We cannot choose facts, obviously, but we still have great freedom. We can choose to look for light or to wallow in darkness. We can choose to find meaning or we can choose to see none. We can choose to be motivated towards a thing by love, or repelled away from something else by fear. What we desire is reflected in the world we create to live in, not in the banal sense of wish-fulfillment, but in a deep reflection of our truest desires.

Now let me make one simple comment: if our constructed reality determines our course of action, then it is in the truest and most accurate sense of the world what we believe. After all, beliefs are not about what we think is true, or even what we think we think is true (it’s possible to get that wrong), but rather about the things that must be true based on our actions. Therefore, another expression for constructing our reality is simply “having faith”. This need not be faith in a religious sense, secular humanists have ideals in which they have faith as firm and unwavering as any of the devout followers of religion, but it is absolutely faith.

Let me go farther and say that creating art is essentially the same thing as creating our own reality. There is a kind of symmetry between sub-creation as the creation of art and sub-creation as the creation of meaning in our day-to-day lives. I don’t think there is such a vast difference between Tolkien’s work creating Elven dialects vs. a parent’s work in feeding their child. To me: creation of meaning is creation of meaning. Faith, therefore, is not only about the construction of our beliefs, but also about the construction of art.

Lastly, let me bring back the concept of shared, constructed reality like the world of Harry Potter. When we read a book, watch a movie, listen to a poem, or hear a song we are not passively receiving information (like the failed theory of naïve realism), but are actively participating with the creator in constructing a shared reality. The audience, the performers, and the authors are all playing different parts, but in the very same activity.

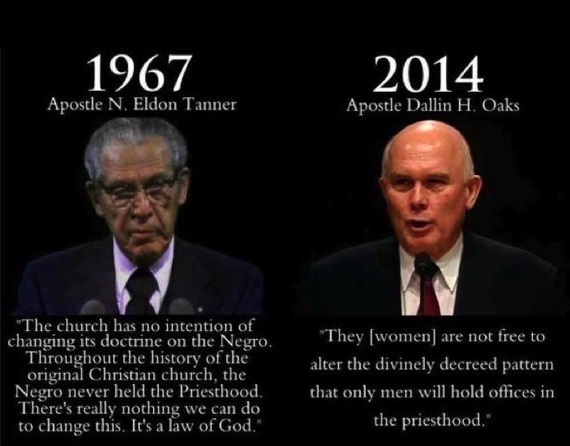

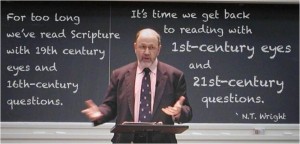

In the end: The rules for what we should believe are related to the rules for what art we should create which are related to the rules for what art we should choose to participate in as the audience. And they amount, I think, to simply this: always strive for something truer, better, and more beautiful.

Living in a Nightmare

Which brings me back to Game of Thrones. The first pebble that started the avalanche that has become this article was a post from The Vulture called Seitz on Game of Thrones Season 4: TV’s Most Exhilarating Nightmare. The piece begins:

Game of Thrones is not the deepest, most subtle, or most innovative drama on TV. It is an example of what used to be called “meat-and-potatoes” storytelling: an R-rated yet classically styled epic. It’s mainly concerned with riveting the viewer from moment to moment, often through sex, violence, or intrigue, while keeping a vast fictional world, a complex plot, and a preposterously overpopulated cast straight in the viewer’s mind.

Does this sound like the kind of constructed reality in which you would like to exist? Not me. It’s not even the sex or violence per se that are the problem, but the fact that they are used as short-term goads to keep us interested. To the extent that these goads are linked directly into our “reptilian brains” (see next quote) they are essentially nihilistic. The next paragraph goes on:

Along with Hannibal, this is the most joyous, at times exhilarating nightmare on TV. Considering how unrelentingly bleak this world is — a State of Nature in which most characters are ruled by their reptilian brains, and those who show kindness or mercy tend to suffer for it — there’s no reason why it should be anything but off-putting.

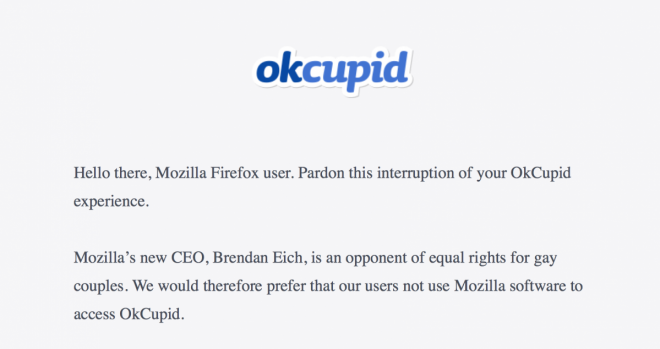

But of course, there is a reason why it’s not off-putting: spectacle. Which brings me to a more recent piece on Game of Thrones called Rape of Thrones. The article ponders why it is that the HBO show has felt the need to deviate from the text of the books in the particular way that it does. Obviously it has to make changes (for length if nothing else), but why has the show chosen not once but twice to render a consensual sexual encounter (in the books) into rape (in the show)?

It seems more likely that Game Of Thrones is falling into the same trap that so much television does—exploitation for shock value. And, in particular, the exploitation of women’s bodies. This is a show that inspired the term “sexposition,” and a show that may have created a character who is a prostitute so as to set as many scenes as possible in brothels.

So you have to ask yourself, what kind of a person voluntarily inhabits a world where women are being degraded purely to sate his animal interest? Who willingly goes along with that? Who wants to help create that world?

That’s not the only problem, however, and Game of Thrones is not my only target. I was also struck by an article(again, from Vulture) called Why Captain America Is Only Interesting If He’s a Prick. The article just elaborates on the headline: Captain America is devoid of artistic merit when he’s a good guy.

In 2014, of what artistic good is a flawlessly nice soldier? Can’t we get at least a little rough and dirty with this 75-year-old warhorse?

On one level, this (and the popularity of anti-heroes in general) is just a furtherance of “a silly idea” C. S. Lewis had already noted in his lifetime:

A silly idea is current that good people do not know what temptation means. This is an obvious lie. Only those who try to resist temptation know how strong it is… A man who gives in to temptation after five minutes simply does not know what it would have been like an hour later. That is why bad people, in one sense, know very little about badness. They have lived a sheltered life by always giving in.

So I just don’t buy this argument that only if we have characters who revel in immoral behavior can we have a meaningful conversation about morality.

This topic is more than I can handle conclusively in a single post, but here’s where I’d like to wrap things up for now.

Moral art does not have to be saccharine, optimistic, or “nice” any more than the actual creation made by God Himself is saccharine, optimistic, or “nice”. The two greatest arguments against God, in my mind, are the Problem of Evil and the hidden god. Why, if God is so good, is there so much suffering? And why, if God wants us to know Him, does he not make Himself obviously present? If the greatest creation of all can cause such incredible pain and confusion, then obviously we have absolutely no reason to suspect that our sub-creations ought to be relentlessly, oppressively cheerful.

Bearing that in mind, however, art is creation, and it is therefore morally significant in ways that are complex and open to interpretation and exploration. My point is not so much “no one should watch Game of Thrones“ as it is that we should all realize that what we watch literally contributes to the creation of the world we inhabit. That’s a big deal. It’s something to think about seriously.

I don’t think that the answer is to try and wall ourselves off from anything that challenges us or makes us sad, but I do think that we ought to avoid deliberate exploitation of sex and violence to hook viewers (because it is nihilistic) and also that we ought to seek out art that reaffirms the validity of moral striving. This will mean different things to different people. I’m not suggesting any kind of top-down censorship. I’m talking about bottom-up self-control in what we choose to participate in.

I don’t know all the answers. I just think, based on my theories of constructed reality, that the problem is more important than most folks realize. I believe there is deep significance to what we choose to consume as mere entertainment, and that it is worth thinking about.