The whole global warming issue is pretty controversial, and one of the reasons for that is that–no matter what the consensus on the science might be–there’s actually a long and convoluted path from “human carbon emissions make the world warmer” to answering the question “what should we do about it?”

One of the big uncertainties, of course, is the cost-benefit analysis of policies designed to slow global warming. That’s what the Freakonomics guys did in one of their chapters from Super Freakonomics, and their conclusion was that–assuming climate change is real–there might not be any policy to stop it that is worth the cost. That claim, as you can imagine, landed them in some hot water.[ref]Time, The New Yorker, and many, many others weighed in as well. Questioning the global warming orthodoxy, which includes policies as well as science, is a big deal.[/ref]

But there are other uncertainties as well. So the planet gets warmer. So ice at the poles melts and sea levels rise, right? Well, maybe not so fast:

It’s a nagging thorn in the side of climatologists: Even though the world is warming, the average area of the sea ice around Antarctica is increasing. Climate models haven’t explained this seeming contradiction to anyone’s satisfaction—and climate change deniers tout that failure early and often. But a new paper suggests a possible explanation: Variability in the heights of ocean waves pounding into the sea ice may help control its advance and retreat.

That’s Carolyn Gramling writing for Science. She goes on to summarize the paper’s theory: warmer climate means lower waves, lower waves means less pounding on sea ice, less pounding on sea ice means slower melting to the point where (as noted above) sea ice in Antarctica is actually growing instead of shrinking.

The reality is that the Earth’s atmosphere and land and ecosystems and the sun’s radiation all work together to form a very, very, very complex system full of all kinds of negative and positive feedback loops that we know nothing about. This is just one example. Ice has been growing since at least 1979 despite projections, but no one had a clue. Now they have one but it is, of course, still just a clue. As science goes: this is great. When the data doesn’t line up with your predictions, it means you’re not understanding something and you have a chance for a new discovery.

But as a basis for expensive, global policy-making goes, this is not so great. The one thing all policies to thwart global warming have in common is making energy more expensive which will have the effect of lowering growth which will have the effect of keeping more people in the developed world in poverty for longer. We can be much more certain about that then we can about the corresponding threat from global warming. After all, we can’t even predict if the sea levels will rise at all, let alone by how much, so how can we begin to make a careful evaluation of the cost/benefit of policies to mitigate this unknown danger?

The consensus on global warming is often trotted out as a cudgel with which to beat skeptics, but this isn’t really effective once you step back and realize that climate change, itself, is only one part of a much, much more complex puzzle.

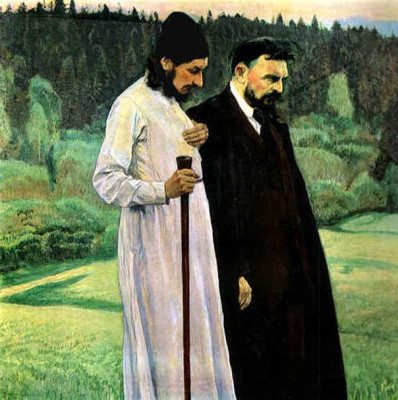

Florensky grew up in the Caucasus. He claimed that his childhood there lent him “an objective, noncentripetal perception of the world, a kind of inverse perspective” which allowed for a “penetration into the depth of things.” The Caucasus is a wild and mysterious region with snow-capped mountains, deep ravines, and roaring rivers. It exerted a tremendous influence on Russian writers, and although I had read extensively on it, nothing prepared me for my first glimpse of it. Pictures can never convey just how remarkable it is. I then understood instinctively Tolstoy’s laconic cry, “the mountains, the mountains,” and I confess to being a little awestruck even today.[ref]Some of my favorite books on this topic are Leo Tolstoy’s Hadji Murat, Mikhail Lermontov’s A Hero of Our Times, and Lesley Blanch’s The Sabres of Paradise: Conquest and Vengeance in the Caucasus. These give an idea of the pull that the Caucasus can have on the imagination.[/ref] I share this because there really is a feeling there of a “native, solitary, mysterious and infinite Eternity, from which everything flows and to which everything returns,” as Florensky described it. Paradoxically, it was this other-wordly feeling that Florensky claimed enabled one to see the world as it really is. “The child has absolutely precise metaphysical formulas for everything other-worldly, and the sharper his sense of Edenic life, the more defined is his knowledge of these formulas.” It is hard to imagine someone like Wallace Stegner concurring with Florensky’s definition of objectivity, yet as Nathaniel noted, the scientific narrative has increasingly tended to absorb and adapt religious ones, resulting in something not far removed from Florensky’s objectivity.[ref]See the multiple examples in Carl Youngblood’s recent MTA

Florensky grew up in the Caucasus. He claimed that his childhood there lent him “an objective, noncentripetal perception of the world, a kind of inverse perspective” which allowed for a “penetration into the depth of things.” The Caucasus is a wild and mysterious region with snow-capped mountains, deep ravines, and roaring rivers. It exerted a tremendous influence on Russian writers, and although I had read extensively on it, nothing prepared me for my first glimpse of it. Pictures can never convey just how remarkable it is. I then understood instinctively Tolstoy’s laconic cry, “the mountains, the mountains,” and I confess to being a little awestruck even today.[ref]Some of my favorite books on this topic are Leo Tolstoy’s Hadji Murat, Mikhail Lermontov’s A Hero of Our Times, and Lesley Blanch’s The Sabres of Paradise: Conquest and Vengeance in the Caucasus. These give an idea of the pull that the Caucasus can have on the imagination.[/ref] I share this because there really is a feeling there of a “native, solitary, mysterious and infinite Eternity, from which everything flows and to which everything returns,” as Florensky described it. Paradoxically, it was this other-wordly feeling that Florensky claimed enabled one to see the world as it really is. “The child has absolutely precise metaphysical formulas for everything other-worldly, and the sharper his sense of Edenic life, the more defined is his knowledge of these formulas.” It is hard to imagine someone like Wallace Stegner concurring with Florensky’s definition of objectivity, yet as Nathaniel noted, the scientific narrative has increasingly tended to absorb and adapt religious ones, resulting in something not far removed from Florensky’s objectivity.[ref]See the multiple examples in Carl Youngblood’s recent MTA