So the first problem I noticed with this NYT op-ed is that it is based on research that is not research. Nancy Ditomaso makes the stunning observation that job-seekers depend on social networks to get jobs. The fact that Ditomaso appears to think that this required “research” to discover–and that the discovery warrants an op-ed piece–suggests quite a lot about Ditomaso. Starting, for example, with the fact that if you’re looking for someone who has anything like expertise on job-searching you should look elsewhere. Seriously, has she never heard of the term “networking”?

Still, despite the fact that the starting point of this piece is basically “when it rains things get wet”, the fact that it appears in the NYT (even the blog section) shows that if you add charges of racism to an otherwise banal story, you’ll make waves. Or at least ripples. Ditomaso’s argument is that since people use their social networks to get jobs, and since social networks are correlated with race (“we still live largely segregated lives”), and since white people have better jobs, the end result is that white people can effectively discriminate against black people not by discriminating against black people, but by showing favoritism towards white people.

As an observation about systemic inequality, Ditomaso is right. I think it’s a real problem, and I think it’s one that should be taken seriously. But there is a huge problem with the way that Ditomaso addresses this legitimate concern. That problem is that she sees the problem entirely through partisan political lenses, thus intertwining left and right with black and white. That’s a terrible thing to do.

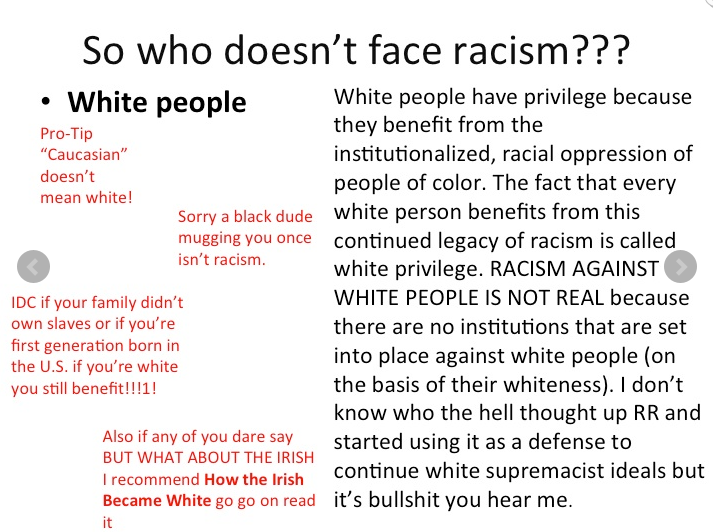

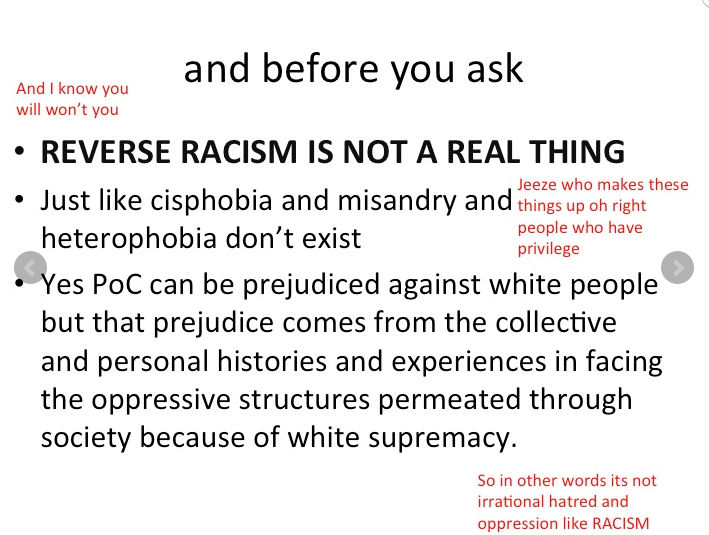

For example, Ditomaso levels the heavy accusation that “despite complaints about “reverse discrimination,” my research demonstrated that the real complaint is that affirmative action undermines long-established patterns of favoritism.” The thing that’s most troubling about her specific reasoning is that she never even considered the possibility that people might oppose affirmative action for the reasons that conservatives actually state as their reasons for opposing affirmative action. For example, many conservatives believe that affirmative action is counter-productive, and they have good empirical reasons for believing that. Ditomaso doesn’t even acknowledge that possibility. More generally, conservatives tend to believe in the ideal of a race-blind society.

This doesn’t actually mean that people would have to abandon their heritage of culture. In past centuries, there was significant discrimination among white people against other white people (such as Irish and Italians), but this kind of discrimination is largely non-existent today. That doesn’t mean that white people of Irish or Italian descent have had to abandon, hide, or deny their heritage. It’s just that the specific categories have been largely subsumed. They are there, and people are aware of the stereotypes (positive and negative), but they don’t seem to really matter.

That is the kind of future that conservatives would like to see: the same process of integration that brought various European ethnic groups into tolerant interdependent existence continuing to grow to incorporate all races into a common humanity. That’s not such a bad vision. It’s definitely not a racist vision. And it’s easy to see why conservatives might feel that affirmative action obstructs this progress, by entrenching racial differences in society and law. Ditomaso doesn’t seem to see any irony at all in lamenting that we’re still segregated, and then calling for race-based differential treatment. Conservatives, on the other hand, would love to live in a world where favoritism still exists (if you think that’s going to be stamped out, you’re insane) but social networks are no longer strongly correlated with race.

But Ditomaso isn’t having any of that. We never get to have that discussion. It is cut off at the knees by her myopic insistence that opposition to affirmative action has to be about one of two things: white people don’t like giving black people jobs (“reverse-discrimination”) or white people just really like giving white people jobs (favoritism). Given this whopper of a false-choice dichotomy, the results of her study are not nearly as powerful as she thinks they are:

The interviewees in my study who were most angry about affirmative action were those who had relatively fewer marketable skills — and were therefore most dependent on getting an inside edge for the best jobs. Whites who felt entitled to these positions believed that affirmative action was unfair because it blocked their own privileged access.

Yes: it must be about entitlement and white privilege. The possibility that the other side of the political aisle actually has sincere desires to improve race relations but simply a different view about how to accomplish that is not even entered for consideration.

Please note, by the way, that I’m not denying the existence of entitlement and white privilege. I think these are concepts that do exist. Of course a part of the desire for conservatives for racial integration is that it by white racial integration: integration into a white culture as opposed to integration into a new, pan-racial culture. Everyone prefers what is familiar. There are no angels on earth, and everyone’s politics are going to be tainted with self-interest or prejudice to some degree. The fact that conservative views on race are not perfect shouldn’t be used as an excuse to pretend they are not good. Nor, by the way, do I think this is such a big deal. A couple of centuries ago we would have been talking about the need to assimilate Irish immigrants into American culture. Now we all celebrate St. Patrick’s Day. Clearly integration is intrinsically a two-way street, so I just don’t think that white or black unease with integration should be a dealbreaker for this plan.

I’m not writing this piece because I think America has no problems with race. That would be laughable. I’m writing this because it seems that the only folks who feel at liberty to discuss race come from a particular political viewpoint. And that hamstrings the discussion and also our progress. If there’s one thing I’d like to see change about America’s race dialogue, it would be to make it a dialogue. To actually have a diversity of opinion. I think affirmative action is a terrible idea in practice, but I don’t question the sincerity of those who advocate for it. It’d be nice if that good faith was a two-way street.

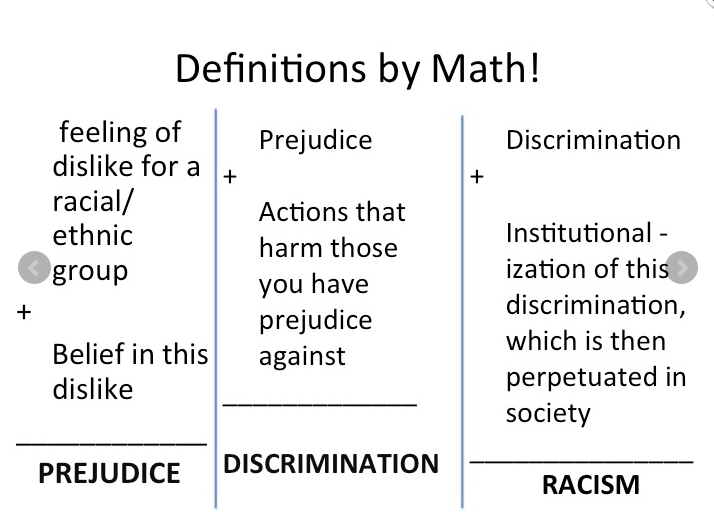

Another way to look at it is Hanlon’s Razor, which states: Never attribute to malice that which is adequately explained by stupidity. The gist of this is that when something bad happens, don’t assume malice. It could be incompetence. It could be stupidity. It could be bad incentives. It could be ignorance. There is no doubt that the combination of social networks and pre-existing racial inequity is self-perpetuating. The outcome is racist. But it’s time we learned to separate between 21st century racism, which is primarily about unintentional perpetuation of pre-existing disparities, and 19th century racism, which was about the belief that some races are intrinsically inferior to others. Using the same terminology to cover innocent (but dangerous and sometimes stupid) behavior and evil behavior is not constructive.

That’s what the title of this article refers to. I’m absolutely not denying the reality of systemic racial injustice in our country. Far from it. I’m saying that the best way forward includes an admission that the battle to be fought in 2013 isn’t the same as the ones that were fought in the 1960s or 1860s. That struggle is not over, but it has changed. Our tactics–and our language–should reflect our past progress if we want to see more progress in the future.

After reading novelist and political commentator Orson Scott Card’s bizarre “thought experiment,”

After reading novelist and political commentator Orson Scott Card’s bizarre “thought experiment,”