A mom’s photo of her post birth body has gone viral thanks to the raw understanding among women that (most[ref]I knew someone who wore skinny jeans without a bump immediately after birth. If you want to run 6 miles a day while pregnant, that may work for you too.[/ref]) women still look pregnant weeks and months after giving birth. It reminds me of Kate Middleton’s post birth photos that showed she, too, had a bump. One week after having my first child, I was at Target, alone (my daughter was still in the hospital) and I got the inevitable “When are you due?” question. I looked the same as I did 6 months pregnant. When I told the lady I was postpartum she looked at me horrified and sprinted away, not allowing me the chance to say “I know I still look pregnant, and it’s OK.” Truth is, most people don’t look like movie stars postpartum, or any other time.

A mom’s photo of her post birth body has gone viral thanks to the raw understanding among women that (most[ref]I knew someone who wore skinny jeans without a bump immediately after birth. If you want to run 6 miles a day while pregnant, that may work for you too.[/ref]) women still look pregnant weeks and months after giving birth. It reminds me of Kate Middleton’s post birth photos that showed she, too, had a bump. One week after having my first child, I was at Target, alone (my daughter was still in the hospital) and I got the inevitable “When are you due?” question. I looked the same as I did 6 months pregnant. When I told the lady I was postpartum she looked at me horrified and sprinted away, not allowing me the chance to say “I know I still look pregnant, and it’s OK.” Truth is, most people don’t look like movie stars postpartum, or any other time.

Month: January 2016

Gun Safety vs. Gun Control

Nicholas Kristof has an excellent piece in The New York Times on what he calls “inconvenient facts” surrounding gun violence and gun laws. These include:

- “The number of guns in America has increased by more than 50 percent since 1993, and in that same period the gun homicide rate in the United States has dropped by half.”

- “A 113-page study found no clear indication that [the assault rifle ban] reduced shooting deaths for the 10 years it was in effect.”

- Overblown fears regarding open-carry and conceal-carry laws.

- “One poll found that 74 percent even of N.R.A. members favor universal background checks to acquire a gun.”

- “New York passed a law three years ago banning gun magazines holding more than seven bullets — without realizing that for most guns there is no such thing as a magazine for seven bullets or less.”

- “Some public health approaches to reducing gun violence have nothing to do with guns. Researchers find that a nonprofit called Cure Violence, which works with gangs, curbs gun deaths. An initiative called Fast Track supports high-risk children and reduces delinquency and adult crime.”[ref]This may be particularly important given that, statistically speaking, gun violence is experienced differently depending on race.[/ref]

Kristof concludes, “In short, let’s get smarter. Let’s make America’s gun battles less ideological and more driven by evidence of what works. If the left can drop the sanctimony, and the right can drop the obstructionism, if instead of wrestling with each other we can grapple with the evidence, we can save thousands of lives a year.”

Give it a read. And then give Nathaniel’s piece on the subject another read.

Atheist + Pro-Life

Kelsey Hazzard, president of Secular Pro-Life, an organization that promotes a pro-life stance based on science, has a excellent piece at Opposing Views about the religious tone of many abortion advocates. Hazzard discusses how this “magical thinking” was the basis of the Roe v. Wade decision and is a current pro-choicers are happy to ride, even if they are stereotypically the kind of people who would promote science first, as long as the result is more pro-choicers and more abortions.

Kelsey Hazzard, president of Secular Pro-Life, an organization that promotes a pro-life stance based on science, has a excellent piece at Opposing Views about the religious tone of many abortion advocates. Hazzard discusses how this “magical thinking” was the basis of the Roe v. Wade decision and is a current pro-choicers are happy to ride, even if they are stereotypically the kind of people who would promote science first, as long as the result is more pro-choicers and more abortions.

Indeed, magical thinking is embedded in Roe v. Wade itself. The majority opinion discusses a variety of views concerning when human life begins… The notion that science is just one possible approach among many is a hallmark of magical thinking. The consensus of modern embryologists, and the beliefs of a civilization that thrived a millennium before the invention of the sonogram, are not equally valid. That the Supreme Court of the United States pretended that they were, and that such a farce remains good law more than forty years later, is an embarrassment to our legal system.

Check out the full piece here.

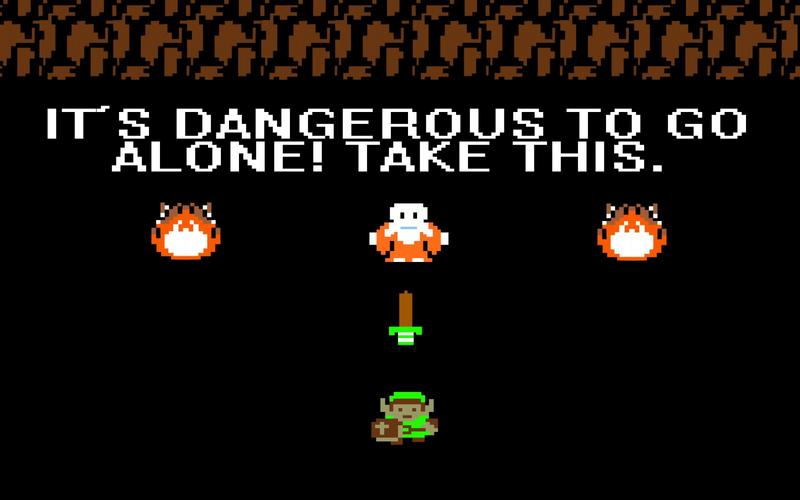

It’s Dangerous to Go Alone

This post is part of the General Conference Odyssey.

This week I’m going to start out with pop culture and Dietrich von Hildebrand before bringing it home to Elder Eldred G. Smith’s talk from the Friday morning session of the October 1971 General Conference: Decisions.

The crux of Dietrich von Hildebrand’s The Heart: An Analysis of Human and Divine Affectivity is that Western philosophy has been wrong to ignore the heart (“the affective sphere” or, in simple terms, our emotional nature) in favor of its obsession with rationality and will. His argument is complex and covers a lot of ground, but here is perhaps the one quote that has stayed with me the most since finishing the book:

If a man were impelled by a Kantian duty ideal to help suffering people by efficient actions of all kinds, but did so with a cool and indifferent heart and without feeling the slightest compassion, he certainly would miss an important moral and human element. It may even be that the gift bestowed on a suffering person by a true and sincere compassion and by the warmth of love cannot be replaced by any benefit we can bestow on him by our actions if these are done without love.

Serving is not enough. Your heart has to be in it.

I believe this is true, but in a way it also confounds our beliefs about obedience. The trick is that we can force our actions to conform to standards, but we cannot directly force our heart to feel a particular way. Anyone can give 10% of their income to tithing, if you just exercise the will power to do it. But how do you make yourself love your neighbor? How do you make yourself love God?

Of course there are good, practical tips for fostering and protecting feelings of love (often discussed in self-help books for marriage or family relationships), but we can’t avoid the fact that our control over our heart is indirect. And, at first, there’s an odd contradiction here between Nephi’s “I will go and do” attitude toward obedience (which is very much centered on action) and the actual greatest commandments: to love God and to love our neighbor involve action, of course, but they are also focused on emotion. So, how do we “go and do” something that relies on our heart feeling a particular way?

We can’t. Not alone, anyway.

This has been a really profound realization for me, and I had it on my mind already as I read Elder Smith’s talk where he said, for example, “the Lord will not permit Satan to try us beyond our ability to resist or withstand his efforts, if we will accept his help.”[ref]Emphasis added.[/ref] That’s a really important qualification, and for me it’s new.

In a sense, of course, the information has always been there. Nephi’s famous “go and do” speech[ref]1 Nephi 3:7[/ref] includes the statement that he knows God will provide a way for us to accomplish the commandments we’re asked to perform, but somehow I’ve always had the idea that this means there is a way—a road or a path—but that we’ve got to walk it on our own. That’s not actually what Nephi said. That’s just how I’ve always heard it.

But going it alone is never a part of the hero’s journey. I’m reminded of the classic 1986 Nintendo game The Legend of Zelda. The hero, Link, gets his first weapon from an elderly man who tells him, “It’s dangerous to go alone! Take this.”

Another example would be Harry Potter’s confrontation with Serpent of Slytherin in the Chamber of Secrets. Prior to the battle, Dumbledore told Harry, “Help will always be given at Hogwarts to those who ask for it.” During the battle, the Sorting Hat appears and gives Harry the Sword of Godric Gryffindor, with which he is able to defeat the basilisk.

You might think it’s a little silly for me to quote children’s books or 1980s video games alongside Catholic theologians all to make a point from a General Conference talk. And I’ll admit, part of it is in fun. But I also strongly believe that there are so many sources of light for us in this world, if we only know where to look for them. In a way, that’s one of the things that reading the General Conference talks helps me to do: calibrate my relation to the Spirit so that I can find sources of inspiration all around me.

And I need that constant reminder. Because, returning to Elder Smith’s talk, “The Lord has made no promise to those who try to go it alone. As soon as you think you can lick the devil alone, on your own, without the Lord’s help, you have lost the battle before you start.”

That exact quote has come back to my mind again and again: “The Lord has made no promise to those who try to go it alone.” I had another chance to feel the bite of that mistake on Sunday. I am a Gospel Doctrine teacher, and I love this calling. There is no calling I would rather have ever, and I try very, very hard to do a good job of bringing the Spirit into my lessons and teach what the Lords would have me teachr.

But I don’t always succeed.

There are basically two variables in how a lesson goes, at least from my perspective. The first is how much I prepare. The second is how I feel as I go into the lesson.

On Saturday, I spent four or five hours working on my lesson, which is longer than the 1-2 hours that I usually spend. I was really pleased with my research and my outline. I felt confident that I had it covered. And when I went in and taught my lesson… it didn’t go very well. Not as well as I’d hoped, anyway. I frequently felt lost as I was teaching, struggling to remember where I’d placed a quote in my notes or unsure about which way to take the lesson when there was not enough time to do everything.

The problem was I thought I could go it alone. I thought I had this one. And so I didn’t rely on the Lord as much as I ought to have.

The sad thing is how many times I’ve had to relearn this lesson. I’ve been teaching for 3-4 years now, and the pattern is always the same. I have to work hard to prepare the lesson and I have to rely on the Lord. In practice, this means I have to be a little bit scared going into it. Hopefully I’ll grow out of that and be able to rely on the Lord with confidence instead of out of nervousness, but the point is: I need to realize that I need help. And then it’s there. As Elder Smith said, “When you desire to do what the Lord wants you to do because he wants you to, then ask him for help; then keeping these laws and commandments becomes easy.”

Here are some quotes from the other talks that I also liked:

The Purpose of Life: To Be Proved by Elder Franklin D. Richards

“Although it is not customary for one to seek out the difficult or unpleasant experiences, it is true that the trials and tribulations of life that stand in the way of man’s growth and development become stepping-stones by which he climbs to greater heights, providing, of course, that he does not permit them to discourage him.”

“A temple, first of all, is a place of prayer; and prayer is communion with God. It is the ‘infinite in man seeking the infinite in God.’ Where they find each other, there is holy sanctuary—a temple.”

“I Know That My Redeemer Liveth” by President John Fielding Smith

“The supreme act of worship is to keep the commandments, to follow in the footsteps of the Son of God, to do ever those things that please him.”

The Only True and Living Church by President Boyd K. Packer

“Some members of the Church who should know better pick out a hobby [piano] key or two and tap them incessantly, to the irritation of those around them. They can dull their own spiritual sensitivities. They lose track that there is a fullness of the gospel and become as individuals, like many churches have become. They may reject the fullness in preference to a favorite note. This becomes exaggerated and distorted, leading them away into apostasy.”

A Time of Testing by Henry D. Taylor

“We will all have our Gethsemane.”

“This Is My Beloved Son” by Loren C. Dunn

“Although the amount of time we spend is important, probably the more important thing is the ability to build our children into our lives.”

Satan’s Thrust—Youth by President Ezra Taft Benon

“The critical and complaining adult will be less effective than the interested and understanding… We must love our young people, whether they are in righteousness or in error.”

—

Here are some of the other talks from this weeks’ iteration of the General Conference Odyssey. Not all the links were ready when this post was finished, however, so check out the constantly updated index for a complete list. You can also follow along by joining the Facebook Group.

- Working Out Our Collective Salvation (G at Junior Ganymede)

- LDS Conference October 1971 – What is Failure? Zion’s Camp and Liberty Jail (J. Max Wilson at Sixteen Small Stones)

- Our Position of Strength (Daniel Ortner at Symphony of Dissent)

- Choose Ye This Day: General Conference or Elvis, the Beatles, and the Rolling Stones (John Hancock at The Good Report)

- I Was So Much Older Then, I’m Younger Than That Now (Ralph Hancock at The Soul and The City)

- Liberty (Michelle Linford at Mormon Woman)

- A Little Bit of Heaven on Earth (Walker Wright at Difficult Run)

- Sustaining Failure (SilverRain at The Rains Came Down)

- Free Agency and God’s Interference (Chastity Wilson at Comfortably Anachronistic)

“A Little Bit of Heaven on Earth”

This post is part of the General Conference Odyssey.

Last year, I made a joke at work about beginning an official book club for the linehaul department at our terminal. About a week later, one of my co-workers was texting all of us a list of books to choose from. We ended up choosing journalist and linguist Christine Kenneally’s The Invisible History of the Human Race, which covered the very Mormon subject of genealogy. The book demonstrates the power of family history–both in regards to genetics and culture–in shaping our personal lives.[ref]There is a good review and summary of the book in The New York Times.[/ref] Research continues to find that the experiences of individuals can be passed along genetically, including major trauma. Findings like this give new meaning to the common LDS/biblical phrase “turn the heart of the fathers to the children, and the heart of the children to their fathers” (Mal. 4:6).[ref] Sam Brown explains, “The priesthood power that Elijah brought to the Latter-day Saints was inextricably linked to covenant theology in several distinctive exegeses of Malachi’s prophecy that the immortal prophet Elijah would “turn the hearts of the children to the fathers and the hearts of the fathers to the children.” In an 1844 sermon, Smith returned to the translation of the book of Malachi–a book he had termed “correct” in the KJV at the conclusion of his New Translation in 1833. “Turn,” he announced, was better rendered “bind or seal,” absorbing the KJV’s rendition of Malachi into Mormon covenant theology. An obscure word in the Authorized Bible found new life in the Mormon temple. In this sealing stood the maturation of the covenants and seals of the first years of the church’s existence. In 1843, Smith taught that Elijah “shall reveal the covenants of the fathers in relation to the children..–and the children and the covenants of the children in relations to the fathers.” Elijah established such covenants that believers “may have the priviledge of entering into the same in order to effect their mutual salvation”” (In Heaven As It Is On Earth: Joseph Smith and the Early Mormon Conquest of Death, 166).[/ref] The idea of creating “a welding link of some kind or other between the fathers and the children” is an at-one-ment of generations. It is intergenerational healing and forgiveness:

Last year, I made a joke at work about beginning an official book club for the linehaul department at our terminal. About a week later, one of my co-workers was texting all of us a list of books to choose from. We ended up choosing journalist and linguist Christine Kenneally’s The Invisible History of the Human Race, which covered the very Mormon subject of genealogy. The book demonstrates the power of family history–both in regards to genetics and culture–in shaping our personal lives.[ref]There is a good review and summary of the book in The New York Times.[/ref] Research continues to find that the experiences of individuals can be passed along genetically, including major trauma. Findings like this give new meaning to the common LDS/biblical phrase “turn the heart of the fathers to the children, and the heart of the children to their fathers” (Mal. 4:6).[ref] Sam Brown explains, “The priesthood power that Elijah brought to the Latter-day Saints was inextricably linked to covenant theology in several distinctive exegeses of Malachi’s prophecy that the immortal prophet Elijah would “turn the hearts of the children to the fathers and the hearts of the fathers to the children.” In an 1844 sermon, Smith returned to the translation of the book of Malachi–a book he had termed “correct” in the KJV at the conclusion of his New Translation in 1833. “Turn,” he announced, was better rendered “bind or seal,” absorbing the KJV’s rendition of Malachi into Mormon covenant theology. An obscure word in the Authorized Bible found new life in the Mormon temple. In this sealing stood the maturation of the covenants and seals of the first years of the church’s existence. In 1843, Smith taught that Elijah “shall reveal the covenants of the fathers in relation to the children..–and the children and the covenants of the children in relations to the fathers.” Elijah established such covenants that believers “may have the priviledge of entering into the same in order to effect their mutual salvation”” (In Heaven As It Is On Earth: Joseph Smith and the Early Mormon Conquest of Death, 166).[/ref] The idea of creating “a welding link of some kind or other between the fathers and the children” is an at-one-ment of generations. It is intergenerational healing and forgiveness:

For we without [our dead] cannot be made perfect; neither can they without us be made perfect. Neither can they nor we be made perfect without those who have died in the gospel also; for it is necessary in the ushering in of the dispensation of the fulness of times, which dispensation is now beginning to usher in, that a whole and complete and perfect union, and welding together of dispensations, and keys, and powers, and glories should take place, and be revealed from the days of Adam even to the present time. And not only this, but those things which never have been revealed from the foundation of the world, but have been kept hid from the wise and prudent, shall be revealed unto babes and sucklings in this, the dispensation of the fulness of times (D&C 128:18).

Through the sealing keys and covenants, we are integrated into a cosmological family, stretching from pre-mortality to the Adamic origins of the human race to worlds without end. Being “made perfect” through this integration is to become whole: to have an eternal sense of belonging and identity.[ref]One study finds that children benefit from knowing more about their ancestors, leading to a greater sense of identity and well-being.[/ref] Salvation and divinity is found in family.

I was reminded of this during Loren C. Dunn’s talk, in which he states that the “special ties between parents and children…tend to make the family organization a little bit of heaven on earth.” He goes on:

I am impressed by the fact that the plan of redemption and salvation for all mankind was worked out between a father and his son, even God the Father and his Son Jesus Christ. I believe that one of the significant parts of the Joseph Smith story was when the angel Moroni told young Joseph to go to his father and relate to him everything that had happened. Even in the restoration of the gospel of Jesus Christ, the Lord was careful to recognize the relationship of this young boy to his father, and he made sure that nothing would damage it. Yes, the association of a father with his children can and should be a very special one.

Author and historian Dan Vogel has used Joseph Smith’s family dynamics as an interpretive lens to Smith’s prophetic career.[ref]See his Joseph Smith: The Making of a Prophet (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 2004). While Vogel is a secular critic of Mormon origins, I think his analysis provides valuable insights for believers as well.[/ref] Whether resolving conflict within his own family or mending the fractured nature of human history,[ref]See Philip L. Barlow, “To Mend a Fractured Reality: Joseph Smith’s Project,” Journal of Mormon History 38:3 (Summer 2012): 28-50.[/ref] Joseph Smith’s project was all about family. Dunn’s reminder that the architects behind the Plan of Salvation were family members is a subtle, but profound insight into what Joseph Smith called “the grand fundamental principle of Mormonism“: friendship. Or, perhaps more appropriate, kinship. “Love,” taught Joseph Smith, “is one of the chief characteristics of Deity, and ought to be manifested by those who aspire to be the sons of God. A man filled with the love of God, is not content with blessing his family alone, but ranges through the whole world, anxious to bless the whole human race.”

If you can’t tell, I wasn’t all that impressed with this session. However, I thought Franklin D. Richards provided some food for thought when he said, “The story of most men and women who attain a degree of greatness and achievement is generally the story of a person overcoming handicaps. It appears that there are lessons that can only be learned through the overcoming of obstacles.” What hit me the hardest, though, was his point about sacred truths that emerge from suffering: “One of the great truths that came from the so-called prison temple, Liberty Jail, had to do with priesthood and Church government.”

I had to really dig for some good stuff this session. I’m hoping the next one is better.[ref]You’ll notice that I didn’t mention most of the talks. A quick rundown as to why: Joseph Fielding Smith’s talk was a nice testimony. Nothing more. I don’t have much to say about it one way or the other. Boyd K. Packer’s was Mormon triumphalism at its finest. Henry D. Taylor’s was a pretty poor handling of the problem of evil. Eldred G. Smith’s wasn’t bad, but wasn’t great. Unmemorable and largely unquotable. Ezra Taft Benson’s reminded me of the parents who think that AC/DC stands for Anti-Christ/Devil Child or KISS stands for Knights in Satan’s Service. It was extreme to the point of parody.[/ref]

—

Here are some of the other talks from this weeks’ iteration of the General Conference Odyssey. Not all the links were ready when this post was finished, however, so check out the constantly updated index for a complete list. You can also follow along by joining the Facebook Group.

- It’s Dangerous to Go Alone (Nathaniel Givens at Difficult Run)

- Working Out Our Collective Salvation (G at Junior Ganymede)

- LDS Conference October 1971 – What is Failure? Zion’s Camp and Liberty Jail (J. Max Wilson at Sixteen Small Stones)

- Our Position of Strength (Daniel Ortner at Symphony of Dissent)

- Choose Ye This Day: General Conference or Elvis, the Beatles, and the Rolling Stones (John Hancock at The Good Report)

- I Was So Much Older Then, I’m Younger Than That Now (Ralph Hancock at The Soul and The City)

- Liberty (Michelle Linford at Mormon Woman)

- Sustaining Failure (SilverRain at The Rains Came Down)

- Free Agency and God’s Interference (Chastity Wilson at Comfortably Anachronistic)

Religion Is Good for Families

Is religion bad for kids and for families? One recent study claims that religious kids are less altruistic than their secular peers. Now, this claim is based on kids in a non-random sample (not) giving stickers to each other. Stickers. But sociologist W. Bradford Wilcox explains why those eager to use studies like this to point out religion’s deficiencies are missing the mark:

On average, religion is a clear force for good when it comes to family unity and the welfare of children — the most important aspects of our day-to-day lives. Research, some of it my own, indicates that on average Americans who regularly attend services at a church, synagogue, temple or mosque are less likely to cheat on their partners; less likely to abuse them; more likely to enjoy happier marriages; and less likely to have been divorced.

He continues by pointing to data from the General Social Survey demonstrating that religious service attendance “seems to be a net positive for marriage in America” (it increases marriage and fertility worldwide as well). Further research “tells us that religious parents spend more time with their children.” Finally, “religious teens are more likely to eschew lying, cheating and stealing and to identify with the Golden Rule. Children from religious families are “rated by both parents and teachers as having better self-control, social skills and approaches to learning than kids with non-religious parents,” according to a nationally representative study of more than 16,000 children across the United States.” Despite its flaws, “religion in America is not the corrosive influence that it’s often made out to be nowadays. On the contrary, for many Americans, it’s a source of inspiration that redounds not only to their benefit, but also to their families and communities.”

Check out the full article for lots on interesting research.

Making Time for Books

Since we posted our annual Best Books of the Year review yesterday morning, I thought this recent post over at Harvard Business Review was appropriate. Literary technologist Hugh McGuire describes the constant barrage of digital information day in and day out:

I was distracted when at work, distracted when with family and friends, constantly tired, irritable, and always swimming against a wash of ambient stress induced by my constant itch for digital information. My stress had an electronic feel to it, as if it was made up of the very bits and bytes on my screens. And I was exhausted.

To his horror, he realized that his constant immersion in this easy, instantaneous web of mental overstimulation caused him to

read just four books in all of 2014. That’s one book a quarter. A third of a book per month. I love reading books. Books are my passion and my livelihood. I work in the world of book publishing. I’m the founder of LibriVox, the largest library of free public domain audiobooks in the world; and I spend most of my time running Pressbooks, an online book production software company. I might have an unpublished novel in a drawer somewhere. I love books. And yet, I wasn’t reading them. In fact, I couldn’t read them. I tried, but every time, by sentence three or four, I was either checking email or asleep.

Drawing on new neuroscience research, McGuire points out that the constant novelty triggers the release of dopamine, conditioning us to continually seek out potential pleasure in new things (e.g. new emails, Facebook updates, etc.). This constant bouncing around between topics also depletes our brain’s energy. McGuire suggests three rules by which we can diminish the stress of information overload and learn to read again:

- When you get home from work, put away the laptop and iPhone.

- After dinner, don’t turn on Netflix, the TV, or the Internet.

- No glowing screens in the bedroom (Kindle is ok).

While I don’t do these exactly, I have made a rule of “no iPhone or Internet one hour before bed.” I finally have a set bedtime every night before work. Granted, I’ve only been doing this for about a week or so, but I can already feel a difference. If you saw anything in our Best Books post that you would like to read, but just can’t seem to find the time, give the rules above a try.

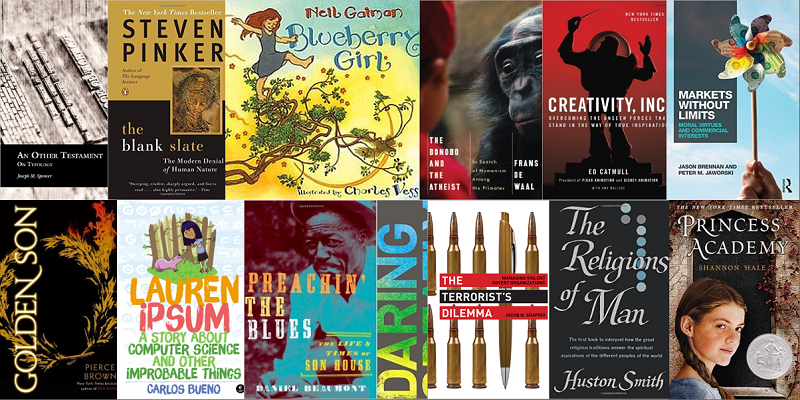

Difficult Run Best Books of 2015

Continuing the tradition that we started last year, I asked the DR Editors to each pick their five favorite books from 2015.[ref]Not everyone followed the rules. That’s how we roll.[/ref] Once again, we’ve got a fantastic, eclectic selection of books. Without further ado, and in no particular order, here are best books that we read last year.[ref]Note: that doesn’t mean they were published last year.[/ref]

Walker Wright

Brown’s approach to shame and vulnerability has had a significant impact on my worldview, including how I interpret my religion. However, my exposure to her work over the last couple years was largely through her TED talks, articles, and professional counseling. I finally read a couple of her books this year, Daring Greatly being my favorite. The book is a fantastic mix of research, anecdotes, and application. The insights within it are themselves therapeutic, providing a language capable of capturing many of the turbulent emotions we experience. The result is better self-understanding and increased self-awareness. A paradigm shifting book.

As a huge Pixar fan, I expected to enjoy the book. I didn’t expect it be one of the most enthralling management books I’ve ever read. Stanford’s Robert Sutton was right when he described it as, “One of the best business/leadership/organization design books ever written.” The narrative acts as both a biography of Pixar and an investigation into its organizational structure and managerial styles. The process of creativity is explored, revealing the importance of autonomy, candid discussion, and the expectation of failure. Perhaps the biggest takeaway, however, is that the collective brain is the creative brain. High-quality innovation spurs from the constant flow of information and ideas through a network of diverse people and backgrounds. Managers should read this, yes, but so should anyone interested in embarking on a creative endeavor.

The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion (Jonathan Haidt)

My experience with Haidt prior to reading his book was similar to that of Brown’s above. I had watched his TED talks and lectures and read a number of his articles. Plus, he started showing up over at the libertarian site/magazine Reason. I was familiar with his Moral Foundations Theory and found his discussion of moral psychology absolutely fascinating. Yet, despite being familiar with his work, his book yielded an enormity of new, illuminating details about human nature. His emphasis on the primacy of emotions (the elephant) over reason (the rider) as well as our evolutionary nature as social creatures paints a vivid picture about what it is to be human. Given the often absurd assumptions about human nature we find in the 21st-century Western world, this is refreshingly rooted in reality. A much-needed book.

Markets without Limits: Moral Virtues and Commercial Interests (Jason Brennan and Peter Jaworski)

“If you may do it for free, you may do it for money.” That is the premise of this meticulously argued book by Georgetown philosophy professors Brennan and Jaworski. Economist Bryan Caplan has identified what he calls the anti-market bias among voters and the authors demonstrate why this bias is unfounded. Most talk about the “moral limits of markets” focus on something other than the actual market. For example, a market in slaves doesn’t prove that markets are problem, but that slavery itself is wrong and would still be wrong if done for free. The authors go through the objections of various commodification critics and convincingly show that their arguments are (1) faulty in their logic and/or (2) not grounded in empirical social science. The arguments are powerful and should fundamentally change the nature of the debate. Should be the starting point for any discussion about markets and morality.

An Other Testament: On Typology (Joseph Spencer)

Philosopher Joseph Spencer is one of the most careful readers of scripture in modern Mormonism and this book puts his skill on full display. A stellar combination of close textual analysis, biblical scholarship, and theology, Spencer explores the tension between two different interpretations of Isaiah within the Book of Mormon: Nephi’s collective, covenantal approach vs. Abinadi’s Christological, individualistic view. Spencer’s book is evidence of the kind of deep, intricate reading that can be accomplished through constant study of the text. What’s even better is that Spencer’s reading can accommodate both sides of the historicity debate (though perhaps leaning more favorably toward those championing historicity). One of the most engaging and enlightening books on the Book of Mormon I have ever read.

Ro Givens

Lean In: Women, Work, and the Will to Lead (Sheryl Sandberg)

I know there were a lot of complaints about this book, but I say, that’s insanity. Even if you’re not in business, even if you didn’t start life in the upper class (and will never approach it), you can get insight from Sheryl’s life. Love her.

This book is adorbs. And hilarious. It was the first chapter book my 6 year old asked me to keep reading, and he then asked me to start it again when we finished.

Princess Academy (Shannon Hale)

Another piece of evidence that middle grade fiction > young adult fiction. The writing is better, the message is better (ie, exists), and I’m not embarrassed to admit that I like it. This book has strong female characters and is about the importance of education, cooperation, community, and friendship. #Mormon #represent

Lauren Ipsum: A Story About Computer Science and Other Improbable Things (Carlos Bueno)

A fairy tale about problem solving. Alice in Wonderland meets Computer Science (theory). Adorable and perfect. Read it myself, and now my kids are laughing along while I read it to them.

(FAQ: Yes, I like children’s lit. I read more on my own than to my kids.)

Allen Hansen

Preachin’ the Blues: The Life and Times of Son House (Daniel Beaumont)

Continuing my reading of blues biographies, I picked up this one about a man whose music electrified me when I first heard it. A feel to it which is completely out of this world. The new crop of blues biography are interested in getting behind the mythology of the blues and into the murky details of the musicians lives. House grew up in a decently educated home with a religious background, found religion, found the blues, travelled around the south quite a bit, experienced racism and oppression, worked all sorts of manual labor only somewhat removed from slavery, went to prison, moved north during the war years and was rediscovered the same year that massive race riots broke out in his city. The bigger picture of black history in 20th century America is covered from House’s perspective, so you get an idea of how an individual experienced religion, navigated racism, and responded to various challenges. Life was no monolith, especially for bluesmen rebelling against the strictures of society. There is also a sense of profound tragedy in Son House’s life, an intelligent man of significant ability who could never conquer his twin demons of alcohol and womanizing.

The Terrorist’s Dilemma: Managing Violent Covert Organizations (Jacob N. Shapiro)

I read quite a few books on terrorism last year, but this one stands out. Shapiro looks at terrorist organizations from a management perspective. Terrorist leaders, it turns out, use Excel spreadsheets, handle time-off requests, and issue write-ups in order to run terrorist activities, but the stakes (naturally) are much higher than they would be in legitimate corporations. The tighter the control, the more the paperwork the greater the risk of being compromised. That Excel spreadsheet can cost your life if discovered, but without it you might not be able to counter waste and theft of resources or prevent operative’s violence from spinning out of control (even for terrorists there is such a thing as too much violence). As Shapiro pointedly observes, terrorists face a major personnel challenge. Someone willing to do horrible things to other human beings is not likely to be an upstanding and conscientious agent or keep violence subordinate and appropriate to achieving political goals. This weakness can be exploited to minimize the ability of terrorists to act. Shapiro analyses multiple terrorist groups from different times and places, showing this common thread, and in the process making them a little less exotic, and more banal.

Strange Fruit: Why Both Sides are Wrong in the Race Debate (Kenan Malik)

You might not expect such a book to be written by someone like Kenan Malik. Malik is a British journalist born in a Muslim family in India, a philosopher of science trained in neurobiology, and a secular humanist on the political left. In the book he traces changing attitudes on race from antiquity to the present where it has become entrenched in the twin forms of scientific race realism and identity politics. He skewers race realists or essentialists, but not as much as he does anti-racists. The former conflate the issue of genetic differences with constructs of race, and the latter transformed cultural and genetic differences into dogmatic philosophy. Both reject enlightenment ideas of universality and scientific rationality. Malik is witty, thought-provoking, and has a great way of getting to core of whatever issue is under discussion.

The War That Ended Peace: The Road to 1914 (Margaret MacMillan)

There is fierce debate over what started the First World War, but this book poses a different question. Why did peace end? Europe was not facing its severest crisis, it actually had a good system in place for preserving peace, but it failed in 1914. There was nothing inevitable about the process, and MacMillan does a great job of unpacking the various social, intellectual and political currents which along with personal factors influenced the small group of decision-makers who ultimately chose war. The writing is very engaging and never dry, painting a remarkable portrait of Europe in the early 20th century. MacMillan knows her stuff, but isn’t afraid to be entertaining, like when she draws (an apt) comparison between Wilhelm of Germany and Toad of Toad Hall.

Yosef Haim Brenner: A Life (Anita Shapira)

Growing up in Israel, Brenner was a legendary figure from our past, a cultural messiah of the founding generation. This is probably the narrowest-interest book of the five, but it is still superb. Brenner was born in a religious Jewish family in 19th century Ukraine, fell in love with secular Hebrew literature, and abandoned his religion. His father retaliated by making him serve in the Russian army so that his religiously-minded brother would be exempt from military service. Unsurprisingly, Brenner suffered from bouts of depression throughout his life. He still had a tremendous attachment to his people and the new Hebrew literature while his unflinching honesty and ascetic lifestyle spun a myth around him even in his lifetime. He moved to Palestine in 1909, and was murdered by an Arab mob in the 1921 riots. Shapira scrupulously avoids the myth, making Brenner’s tortured life all the more compelling.

Monica

Blueberry Girl (Neil Gaiman, Charles Vess – illustrator)

This is a lovely book about all of the gifts a parent wishes for his or her newborn daughter, such as freedom from fear, protection from false friends, and help to help herself. Neil Gaiman wrote the book as a poem, and the rhymes and cadence make it pleasant to read to your own daughter (over and over and over). Charles Vess illustrated the poem with beautiful paintings that show girls exploring the world in a carefree, whimsical way. I was pleased to notice the girls in the paintings are different ages and races with different hairstyles and ways of dressing. I like that variety because I like to think about little girls from many walks of life examining the paintings as their parents read to them and feeling the poem is about them too.

As a Christian deconvert and secular parent, I regret that I miss out on the comfort of praying for my daughter. This book has served as a kind of substitute for me. I’ve read Blueberry Girl to my own girl dozens of times, and it’s been not just pleasant but cathartic to say out loud so many of the hopes I have for her.

Bryan Maack

The Religions of Man (Houston Smith)

One question I think every religious person should ask themselves is “Why I do I believe what I believe?” And part of answering that question is answering why you don’t believe anything else. In order to answer that question, I believe that the very best case must be made for every religion.

Here’s where The Religions of Man by Huston Smith steps in. Smith gives you a sympathetic account of many major world religions–Hinduism, Buddhism, Confucianism, Taoism, Islam, Judaism, and Christianity. The author helps you understand why so many people follow these religions earnestly. If anyone has authority to speak on this topic, Huston Smith does, having practiced Vedanta Hinduism, Zen Buddhism, and Sufi Islam for over a decade each [citation: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ Huston_Smith#Religious_ practice].

I will admit that many of the chapters challenged me to seriously consider why I am a Roman Catholic and nothing else. This experience inculcates a sense of humility and understanding of why people of good will hold to many different religions. But far from descending to syncretism, The Religions of Man illustrates the particular problems that religions are addressing and the diverse solutions that they offer, creating a real chance for the reader to discern among unique options.

The book was originally published in 1958. A new 50th anniversary edition, entitled “The World’s Religions,” was published in 2009 with revisions and an added section on indigenous religions.

Nathaniel Givens

I read over 100 books in 2015, but I’m going to narrow it down to just 5. That’s really hard–in the sense that I don’t like leaving good books out (and I’m leaving a lot of good books out!)–but in actuality it only took me a few minutes of going through my Goodreads reviews from 2015 to pick my top 5. Here they are:

Golden Son: Book II of The Red Rising Trilogy (Pierce Brown)

Golden Son is the second book in the Red Rising trilogy. The first book (Red Rising) was good, but it was a little violent for my tastes and also a little derivative: it was basically Ender’s Game

+ The Hunger Games (Book 1)

. The second book blew me away, however. Pierce Brown took things to a new level in two ways. First: the action was non-stop from start to finish. The phrase “break neck” gets used a lot in describing the pace of a fun adventure book, but it’s never been more true than of this book. There was scene after scene where I thought for sure the characters were dead (or that the resolution would be silly), but again and again Brown pulled it off.Second: the book was much more original thoughtful than the first. This is true in terms of politics and also in terms of characterization. The cast of characters is unusually large but, thanks to the investment you put into Red Rising to get this far, you know who everybody is and how they relate to each other. Like Ender’s Game, we’re dealing with a bunch of geniuses and–like Orson Scott Card–Brown writes intelligently and thoughtfully enough for that to believable. Moreover, the moral/political aspects of the book are deep enough to be truly interesting. They aren’t just an excuse for righteous anger and action, they are really meaningful to the point where it gives you something to think about and (most importantly) really make you identify with the characters. Also: the setting. Started out pretty hackneyed (futuristic sci-fi patterned after ancient Earth mythology), but Brown kept at it so long and so seriously that the result is (1) believable and (2) distinctively his own.

I can’t wait to read Morning Star: Book III of The Red Rising Trilogy when it comes out in February.

The Three-Body Problem (Cixin Liu)

This was the first time that an English-translation of a foreign language (Chinese, in this case) book won the Hugo Award for Best Novel, and boy did he deserve it! There was all kinds of drama in the Hugos in 2015, but the one thing that ended up definitively right was that this book won.

It definitely comes from the “literary sci-fi” end of the genre, which is where you’ll find books like The Handmaid’s Tale, The Road

, or Never Let Me Go

. These are all books by writers who have at least one foot outside of the genre, and they aren’t well received by the folks who grew up on the Holy Trinity of Heinlein, Asimov and Clarke. But me? I love them all. I love the fusion of legit sci-fi (read: “not just time travel”) with literary sensibility, and this is perhaps one of the best examples of that sub-genre. I was hooked from the very first scene, a vivid and beautiful depiction of the chaotic internecine political clashes during the Cultural Revolution and the book never let me go. The sci-fi was serious, in that it was very intense extrapolation of actual cutting-edge theoretical physics. But it never became one of those “look at my engineering prowess!” ego-cruises that bedevil hard sci-fi (looking at you, Ringworld.) That’s because the characters were too sensitively drawn and too human for the science to overshadow them.

What I’m trying to say is that it worked as sci-fi and as literature. And that’s peanut butter and chocolate, right there. It doesn’t get any better.

The Blank Slate: The Modern Denial of Human Nature (Steven Pinker)

Steven Pinker did not pull any punches! In this tour de force he takes on the reigning social science model head-on without apologies and also without taking prisoners. He outlines the social science model as having three essential premises: the Blank Slate (i.e. human nature is socially constructed rather than biologically determined), the Noble Savage (i.e. the trendy obsession with “all natural” foods and opposition to vaccines) and the Ghost in the Machine (there’s more to the mind than the brain and bod). He describes the dogmatic defense of these views in the social sciences this way:

This is the mentality of a cult, in which fantastical beliefs are flaunted as proof of one’s piety. That mentality cannot coexist with an esteem for the truth, and I believe it is responsible for some of the unfortunate trends in recent intellectual life.

The rest of the book is a long, empirically-based attack on all three of these fallacies and, secondarily, an attempt to explain why they are not actually necessary to defend the kind of classical liberal values they are often employed to defend. This is one of Pinker’s most important points: if you defend equality on the basis of the Blank Slate (which is by far the most prevalent philosophical basis for feminism, etc.) then you are actually endangering the value you’re trying to defend. Because the blank slate is false. Gender is not (entirely) a social construction. Men and women are biologically different in meaningful ways that go beyond just anatomy. And if you have erected your theory of equality on that false foundation, then when it gets destroyed–and it will get destroyed eventually–the value you were trying to defend is going to get taken down with it.

Now, it’s worth pointing out that I don’t agree with Pinker all down the line. When he stops talking psychology or neuroscience and starts talking political philosophy he loses me on several occasions. In addition, I find Thomas Nagels repudation of reductionist materialism entirely persuasive, and that means that I find Pinker’s assault on the Ghost in the Machine to be, ultimately, a failure. But that’s his least-important point (there’s a reason the book is named for the Blank Slate and not the Ghost in the Machine) and, in any case, I do think that his critique of the Ghost in the Machine as it relates to the standard model of social science theory has traction. In other words, the kind of dualism he is attacking is unsustainable. I agree him there. But the absolutist physical reductionism he erects in its place is also a failure.

Still, this was great book, strongly argued and full of interesting information that I’m continuing to assimilate into my view of myself and the world.

The Bonobo and the Atheist: In Search of Humanism Among the Primates (Frans de Waal)

This is another brilliant book that I love to both agree and disagree with. Primatologist Frans de Waal has a pretty straightforward objective: demonstrate empirically that the foundations of moral behavior are found in primates (and other mammals). Well, that’s the first half, anyway, and it’s the half that he gets resoundingly right. The experiments and stories–both first-person and collected from others–are fascinating reading and deeply impactful.

I was particularly struck, for example, by his descriptions of how primates care for each other, including the disabled. He described one young rhesus monkey that was born with a condition similar to Down syndrome, and how that monkey was cared for by the rest of the troop and tolerated when she did unusual things (like try to pick a fight with the alpha male) that would have gotten any other monkey a severe beating. He also pointed out fossil evidence that Neanderthals also cared for the disabled who could offer nothing in return.

The book never veered into sentimentality, however. De Waal’s view of primates is clear-eyed, and this led to additional insights into the nature of social order and its relationship to the threat of the violence. He wrote in one passage, however, that after observing a tribe of chimpanzees wait patiently for their turn to use a nut-cracking station to crack nuts that were too tough to crush with their teeth:

I was struck by the scene’s peacefulness, but not fooled by it. When we see a disciplined society, there is often a social hierarchy behind it. This hierarchy, which determines who can eat or mate first, is ultimately rooted in violence… A social hierarchy is a giant system of inhibitions, which is no doubt what paved the way for human morality, which is also such a system.

As with Pinker, however, I disagreed with some of de Waal’s conclusions. In particular, he believed that if you can show the origins of moral behavior then you have found the origins of morality itself. This is a major flaw, and also happens to be another one that is addressed by Thomas Nagel. It’s the basic is/ought fallacy (a topic de Waal addressed explicitly but did not handle satisfactorily) and the rebuttal to it is the same rebuttal to pretty much all forms of relativism: you can’t argue for relativism without enacting objectivism. If you say, “subjectivity holds,” you’ve already made a contradictory, objective statement.

Merely because you can show how a thing arises through evolution doesn’t get you out of this problem. You could explain how humans came to have the ability to reason objectively, but that wouldn’t mean that logic and math were suddenly subjective. It would just prove that somehow evolution managed to get us in touch with non-contingent, objective reason. Same idea here: you can explain how humans came to behave morally or even to understand and think about morality, but it’s a colossal mistake to think that, in so doing, you have proved that morality is “constructed” or in any way subjective any more than reason or logic are. (For fun: let someone try to reason you out of the position that reason is objective. See how that works? It’s a non-starter.)

Surprised by Scripture: Engaging Contemporary Issues (N. T. Wright)

This was one of the first books I read in 2015, and it feels like I read it even longer ago than that, but Goodreads doesn’t lie. I finished it on Jan 9, 2015. This one was a huge eye-opener for me. I am very religious, but I come from a Mormon background, and we don’t always have the most sophisticated grasp on the Bible (relative to other Christians) because we split our attention between the Bible and our unique books of scripture: the Book of Mormon in particular.

So for me to see how N. T. Wright connected all kinds of contemporary political debates to the text of the Bible was incredibly mind-expanding. It really deepened by respect for the Bible and also for the traditions of Protestant and Catholic Christianity. It was not really a surprising experience–I read the book precisely because I already knew I was weak on Biblical understanding–but it was still a humbling one in the best way possible. Humbling because when you see a real expert at work you are too distracted by the beauty and skill of their craft and knowledge to feel bad about your shortcomings.

N. T. Wright’s writing style is engaging and this remains an incredibly important book for me, with a serious and ongoing impact on how I view my own faith.

And now, because I can’t resist, honorable mention. Some additional great fiction I read this year includes:

Cibola Burn (The Expanse) – The fourth book in The Expanse is definitely the best, and is significantly better than the first three. Five was also quite good, and I can’t wait for six.

Half-Resurrection Blues: A Bone Street Rumba Novel – This book blew me away. The prose was my favorite part. In fair warning, there is a lot of vulgarity, but for some reason it didn’t phase me as it usually did. I had to stop the audiobook (which is narrated by the author, fantastically) on more than one occasion just to save what I’d read. (Also: just noticed that the sequel Midnight Taxi Tango

is out!)

Son of the Black Sword (Saga of the Forgotten Warrior) – Larry Correia started as one of those self-publishing sensations who finds a diehard audience (in this case, gun nuts who want to read a mashup of a gun catalog and a zombie-slaying video game) and makes it big. The big question for me is often: what happens next. As you can tell, I wasn’t ever the biggest fan of Monster Hunter International

, but I thought his other series (starting with Hard Magic (The Grimnoir Chronicles)

) was really great. Well, this is his third new series and it is–without any doubt–the best. His writing, plotting, characterization: everything has progressed. This is a guy who, in some ways, got lucky, but then he made it count.

The Cinder Spires: the Aeronaut’s Windlass – Jim Butcher is still my favorite living author, but if The Dresden Files

are not your cup of tea: you should still try this one. The style is totally different, so is the setting, so is the plot, so are the characters. It’s an amazing post-apocalyptic forgotten-technology-as-magic with a crew of unforgettable and awesome characters.

The Path Out of Shadows

We’ve reached our first major milestone in the General Conference Odyssey: we’re wrapping up our first conference. Today we’re covering the Tuesday afternoon session of the April 1971 General Conference. Next week, we’ll be covering the Friday morning session of the October 1971 General Conference. One down, a whole bunch more to go!

The talk that struck me the most from this session was Elder William H. Bennett’s Help Needed in the Shaded Areas, which echoed one of my favorite themes: intellectual humility:

As individuals, we have some limitations when it comes to our understanding of things as they really are. We can see so far, and then the earth and the sky come together, so to speak, and we cannot see beyond.

And then again later:

It is important that we remember also that no matter how intelligent we may be, no matter how hard we work, no matter how good our teachers are or how favorable the other conditions for learning, in our allotted span of years on earth we can master only a very small fraction of the total field of knowledge; and what we do master usually is in a narrowed-down, specialized area. Consequently, we, in and of ourselves, have limitations.

This reminds me a lot of some of the things that Marcelo Gleiser had to say in his recent book The Island of Knowledge: The Limits of Science and the Search for Meaning

. For example: “Because of the very nature of human inquiry every age has its unknowables.”

Now, don’t get me wrong, as an atheist I’m sure Gleiser would not agree to the principles that Bennett is teaching. But that doesn’t mean that the connections are purely spurious, either. Consider another quote from Gleiser:

Both the scientist and the faithful believe in unexplained causation, that is, in things happening for unknown reasons, even if the nature of the cause is completely different for each. In the sciences, this belief is most obvious when there is an attempt to extrapolate a theory or model beyond its tested limits, as in “gravity works the same way across the entire Universe,” or “the theory of evolution by natural selection applies to all forms of life, including extraterrestrial ones.” These extrapolations are crucial to advance knowledge into unexplored territory. The scientist feels justified in doing so, given the accumulated power of her theories to explain so much of the world. We can even say, with slight impropriety, that her faith is empirically validated.

The separation between religion and science is not as stark as many would like us to believe in these days when (again, citing Marcelo), “scientific speculation and arrogance are rampant.” Religion and science are not enemies. They are, fundamentally, siblings. They are two branches of mankind’s pursuit of knowledge that branched off when new tools—from mathematics to telescopes—allowed the study of quantifiable, physical phenomena to become a community project in a way that religion, because of it’s internal, personal nature, can never be.

So there are definitely differences, but there are also commonalities, and it makes sense to talk about “faith” in both religious and scientific contexts. The scientific “faith” that Marcelo talks about is the willingness to extrapolate beyond empirical evidence in the pursuit of intuition. Two of Marcelo’s biggest examples are Newton and Einstein who followed their instincts beyond empirical boundaries:

As Newton had done with his universal theory of gravitation, Einstein extrapolated his new theory of gravity from the solar system—where it was tested—to the Universe, confident that the same physical principles applied everywhere.

As Marcelo pointed out in the previous quote, however, the scientist must then validate her intuitions. Which is essentially the same model that Alma famously presented: even if you can’t muster anything more than a desire to believe: start there. Then experiment. See what happens.

Intellectual humility, the understanding that our knowledge is limited, is the first step to the path towards greater knowledge. Marcelo wrote, “We strive toward knowledge, always more knowledge, but must understand that we are, and will remain, surrounded by mystery.” But, as Elder Bennett said, “we need not walk alone.”

There was one other comment that I wanted to share as well. It came from the session’s closing remarks by President Joseph Fielding Smith: A Witness and a Blessing.

There are good and devout people among all sects, parties, and denominations, and they will be blessed and rewarded for all the good they do. But the fact remains that we alone have the fullness of those laws and ordinances which prepare men for the fullness of reward in the mansions above. And so we say to the good and noble, the upright and devout people everywhere: Keep all the good you have; cleave unto every true principle which is now yours; but come and partake of the further light and knowledge which that God who is the same yesterday, today, and forever is again pouring out upon his people.

The idea that being a Mormon consists in finding truth wherever it may be is famously associated with Joseph Smith and Brigham Young, who often spoke about truth in expansive and inclusive ways. But clearly this vein of our faith didn’t end there. It was still alive and well in the 1970s just as it is today. As members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, we have something unique and precious to offer the world, and it’s our duty to share it. But we do not have a monopoly on truth.

Here are the other posts in this week’s installment of the General Conference Odyssey:

- The Path Out of Shadows (Nathaniel Givens at Difficult Run)

- A Pattern to Live (G at Junior Ganymede)

- LDS Conference April 1971 – A Really Round and Hairy Look at Honesty (J. Max Wilson at Sixteen Small Stones)

- The Shaded Areas of Our Testimony (Daniel Ortner at Symphony of Dissent)

- A People Blessed by Revelation (Ralph Hancock at The Soul and The City)

- Eyes to See (Michelle Linford at Mormon Women)

- You Have Entered the Twilight Zone (Walker Wright at Difficult Run)

- Liminality and Shaded Areas (SilverRain at The Rains Came Down)

- Unborrowed Light (SilverRain at The Rains Came Down)

- He Lives, And There Were Gold Plates!! (Michael Worley at Michael’s Thoughts and Ideas)

- Eyes to See and Ears to Hear (Chastity Wilson at Comfortably Anachronistic)

You Have Entered the Twilight Zone

This post is part of the General Conference Odyssey.

In his book Humilitas: A Lost Key to Life, Love, and Leadership, author and historian John Dickson argues that humility (Greek tapeinos; Latin humilitas) was not a virtue in the Greco-Roman world. In this ancient honor/shame society, humility was most certainly associated with the latter. Humility before the gods or emperors was appropriate, largely because they held the power to end your life. Humility before an equal or a lesser, however, was seen as immoral or unjust. The world order was understood to be rational, with people in their present statuses because they (for lack of a better phrase) deserved it. Yet, Jewish tradition focused on the downtrodden and the humiliated; a tradition borne out of exile and defeat. In the case of Jesus, God Incarnate was placed at the lowest, most shameful place in the ancient world. And from that low point, he revolutionized the moral fabric of Western civilization.

BYU professor Bradley P. Owens has conducted some of the most in-depth studies on humility and its impact on organizational outcomes.[ref]I’ve written on this in more detail at Worlds Without End.[/ref] Owens and colleagues developed a model they call “expressed humility” by focusing their attention “on the expressed behaviors that demonstrate humility and how the behaviors are perceived by others.”[ref]Owens, Michael D. Johnson, Terence R. Mitchell, “Expressed Humility in Organizations: Implications for Performance, Teams, and Leadership,” Organization Science 24:5 (2013): 1517.[/ref] They define “expressed humility” as “an interpersonal characteristic that emerges in social contexts that connotes (a) a manifested willingness to view oneself accurately, (b) a displayed appreciation of others’ strengths and contributions, and (c) teachability.”[ref]Ibid.: 1518.[/ref] A significant finding in Owens’ study was that “expressed humility has a compensatory effect on performance for those with lower general mental ability. In other words, though expressed humility had a relatively small positive impact on performance for those with high general mental ability, expressed humility made a considerable difference in performance for those with low general mental ability.” In fact, “[c]ompared with self-efficacy, conscientiousness, and general mental ability, expressed humility was the strongest predictor of individual performance improvement…”[ref]Ibid.: 1527.[/ref] Humility is the key to growth and development.

I was reminded of all this when William H. Bennett declared in the Tuesday afternoon session,

It is important that we remember also that no matter how intelligent we may be, no matter how hard we work, no matter how good our teachers are or how favorable the other conditions for learning, in our allotted span of years on earth we can master only a very small fraction of the total field of knowledge; and what we do master usually is in a narrowed-down, specialized area. Consequently, we, in and of ourselves, have limitations. Our thinking is often highly selective and segmented and our judgment is often faulty.

Economist Thomas Sowell has argued that “it is doubtful whether the most knowledgeable person on earth has even one percent of the total knowledge on earth, or even one percent of the consequential knowledge in a given society.”[ref]Intellectuals and Society (New York: Basic Books, 2009), Kindle edition, 14-15.[/ref] This realization is likely one of many reasons Nathaniel has written extensively on epistemic humility and its relationship to faith. And it seems that Bennett is addressing this very same concept. He stresses the need “to get at the facts and at the causes and to see relationships among them clearly,” so that “we are in a good position to interpret correctly and to arrive at sound conclusions.” The more “we just fool around with opinions and symptoms, we may prolong our difficulties and postpone the time for arriving at lasting, satisfying solutions.” But given our inability to gather and analyze all the “facts” and “causes,” what are we to do?:

As we journey along through life we, as individuals, come in contact with many shaded areas, twilight zones, and even dark alleys, where we, unless aided by a higher power, are not able to see clearly, to interpret correctly, and to come to sound conclusions. Some of these shaded areas are found in the physical world, some in the intellectual world, and some in the realm of the spiritual. Let us remember, however, that the Lord has said that all things unto him are spiritual (bold mine).

For Bennett, there is a way out of these twilight zones:

If we will just live the way we should and do our part, we can experience what a great strength and blessing the Holy Ghost can be in our lives. It can broaden and extend our horizons and can turn the lights on for us so that we can see more clearly in the shaded areas of life and, in fact, in all areas of our living. Some people seem to be more inclined to disbelieve the scriptures and the teachings of our present-day prophets than they are to believe them. I have said in my heart that if they would put forth the same effort to believe that they do to disbelieve, and would humble themselves, exercise faith, and study diligently, the Holy Ghost would help them, and they would find that they believe many of the things they now think they disbelieve.

Parley Pratt’s description of the Holy Ghost’s power seems apt:

The gift of the Holy Ghost adapts itself to all these organs or attributes. It quickens all the intellectual faculties, increases, enlarges, expands and purifies all the natural passions and affections; and adapts them, by the gift of wisdom, to their lawful use. It inspires, develops, cultivates and matures all the fine-toned sympathies, joys, tastes, kindred feelings and affections of our nature. It inspires virtue, kindness, goodness, tenderness, gentleness and charity. It develops beauty of person, form and features. It tends to health, vigor, animation and social feeling. It invigorates all the faculties of the physical and intellectual man. It strengthens, and gives tone to the nerves. In short, it is, as it were, marrow to the bone, joy to the heart, light to the eyes, music to the ears, and life to the whole being.[ref]Key to the Science of Theology, pgs. 98-99. However, it should be noted that Pratt’s understanding of the Holy Ghost was different from that of modern Mormons. The Pratt brothers “defined the Holy Ghost, or Holy Spirit, as an intelligent, cosmic ether, virtually limitless in extension.” Orson Pratt argued that the Holy Spirit was “the Great First Cause itself” (Terryl Givens, Wrestling the Angel: The Foundations of Mormon Thought: Cosmos, God, Humanity. New York: Oxford University Press, 2014, 125-126).[/ref]

In Bennett’s mind, the Holy Ghost can help us see “things as they really are, and…as they really will be” (Jacob 4:13). The Holy Ghost can help us exit the twilight zones of life and step back into the light. The Holy Ghost can, in the words of Neal A. Maxwell, “lift ourselves above the secular smog.”

While the above talk caught my attention, there were others with some excellent counsel and/or worthwhile quotes. Delbert Stapley reminds the saints that honesty is a major part of the 13th Article of Faith: “Honesty embraces many meanings, such as integrity, sincerity, according to the truth, just, honorable, virtuous, purity of life, moral character, and uprightness in mutual dealings. These principles are required virtues of true Latter-day Saints. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints stands for the highest ideals, principles, and standards known to man.” The talk focused on “the building of character,” explaining that “little omissions lead to more serious errors and subtle practices.” These small omissions range from returning surplus change to the cashier to employees actually giving an honest day’s work. “One can overlook many sins,” he says, “but the sin of dishonesty is most difficult to forgive. We are sympathetic to the weaknesses of men and tolerant in our relations with them, but there is nothing that upsets or disturbs confidence more than dealing with a dishonest individual.”

Paul H. Dunn[ref]Yes, that Paul H. Dunn.[/ref] makes an excellent point about the importance of parent/child relationships and their shaping of individuals:

In today’s fast-moving, materialistic world, unfortunately many fathers place their business affairs ahead of their children. I am appalled as I look around me, as was Eddie Cantor some years ago, when he said that a man will spend a whole week figuring out what stocks to buy with $1,000—but he won’t spend an hour with his child, in whom he has a greater investment. Is it any wonder that many of our young people are troubled with identity problems? We who are older speak of building a better world, but our progress is slow. Real generosity to the future lies, then, in giving all that we have to the present. Now, you young people, listen to the counsel of your parents. They love you. We are not perfect. One day you will stand where we stand, and you will have a similar challenge of rearing your young. Will you go with us the extra mile in trying to understand our true nature and purpose?

While I wasn’t overly impressed with Henry D. Taylor’s talk, I did love this quote from Lorenzo Snow on the testimony he received from the Holy Ghost:

I had no sooner opened my lips in an effort to pray…than I heard a sound, just above my head, like the rustling of silken robes, and immediately the Spirit of God descended upon me, completely enveloping my whole person, filling me, from the crown of my head to the soles of my feet, and O, the joy and happiness I felt! No language can describe the almost instantaneous transition from a dense cloud of mental and spiritual darkness into a refulgence of light and knowledge. … I then received a perfect knowledge that God lives, that Jesus Christ is the Son of God, and of the restoration of the holy Priesthood, and the fulness of the Gospel. It was a complete baptism—a tangible immersion in the heavenly principle or element, the Holy Ghost; and even more real and physical in its effects upon every part of my system than the immersion by water.[ref]He cites Eliza R. Snow, Biography and Family Record of Lorenzo Snow, pg. 8.[/ref]

Finally, Joseph Fielding Smith invites those not of our faith, “Keep all the good you have; cleave unto every true principle which is now yours; but come and partake of the further light and knowledge which that God who is the same yesterday, today, and forever is again pouring out upon his people.”

A satisfying conclusion to the first conference in the General Conference Odyssey.[ref]I didn’t say anything about the talks by LeGrand Richards or Eldred G. Smith. The former was a long, rambling, disjointed hodgepodge of scriptures bolstering Mormon triumphalism and its literal fulfillment of random prophecies (or something). Smith’s talk was a weak sauce attempt to lay out the doctrine of genealogy, priesthood, sealing, and adoption.[/ref]

Here are the other posts in this week’s installment of the General Conference Odyssey:

- The Path Out of Shadows (Nathaniel Givens at Difficult Run)

- A Pattern to Live (G at Junior Ganymede)

- LDS Conference April 1971 – A Really Round and Hairy Look at Honesty (J. Max Wilson at Sixteen Small Stones)

- The Shaded Areas of Our Testimony (Daniel Ortner at Symphony of Dissent)

- A People Blessed by Revelation (Ralph Hancock at The Soul and The City)

- Eyes to See (Michelle Linford at Mormon Women)

- Liminality and Shaded Areas (SilverRain at The Rains Came Down)

- Unborrowed Light (SilverRain at The Rains Came Down)

- He Lives, And There Were Gold Plates!! (Michael Worley at Michael’s Thoughts and Ideas)

- Eyes to See and Ears to Hear (Chastity Wilson at Comfortably Anachronistic)