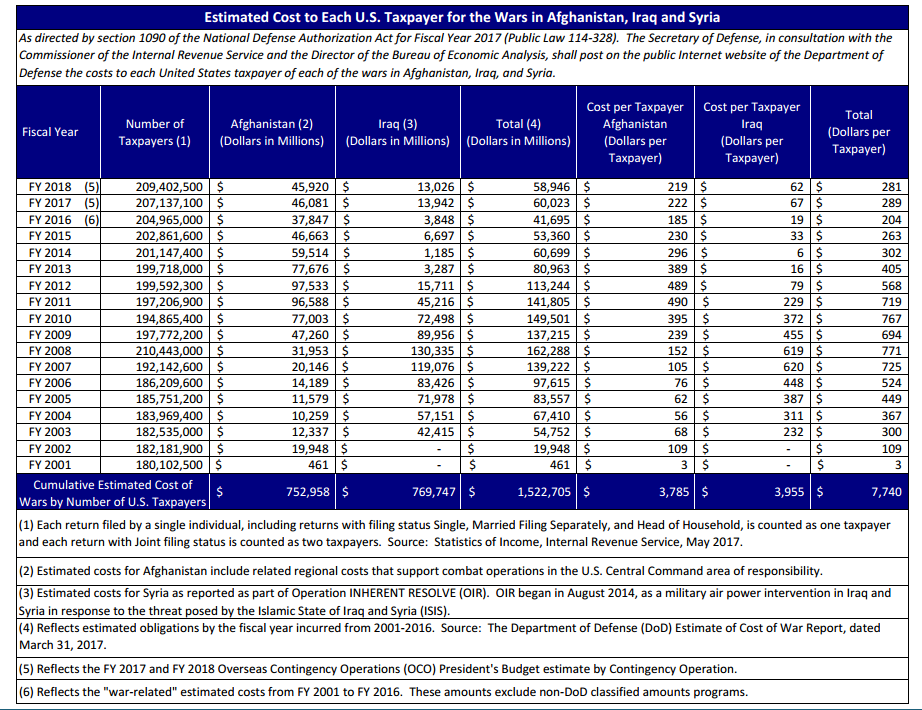

Aside from the human cost, what have wars in Afghanistan, Iraq and Syria cost the American taxpayer? The following comes from the Department of Defense:

Politics

Just Don’t: On Political Passivity

I recently came across a 2012 paper by philosopher Michael Huemer titled “In Praise of Passivity.” Given our current political climate, I found the paper to be rather wise:

When it comes to political issues, we usually should not fight for what we believe in. Fighting for something, as I understand the term, involves fighting against someone. If one’s goal faces no (human) opposition, then one might be described as working for a cause (for instance, working to reduce tuberculosis, working to feed the poor) but not fighting for it. Thus, one normally fights for a cause only when what one is promoting is controversial. And most of the time, those who promote controversial causes do not actually know whether what they are promoting is correct, however much they may think they know…[T]hey are fighting in order to have the experience of fighting for a noble cause, rather than truly seeking the ideals they believe themselves to be seeking.

Fighting for a cause has significant costs. Typically, one expends a great deal of time and energy, while simultaneously imposing costs on others, particularly those who oppose one’s own political position. This time and energy is very likely to be wasted, since neither side knows the answer to the issue over which they contend. In many cases, the effort is expended in bringing about a policy that turns out to be harmful or unjust. It would be better to spend one’s time and energy on aims that one knows to be good.

Thus, suppose you are deciding between donating time or money to Moveon.org (a left-wing political advocacy group) and donating time or money to the Against Malaria Foundation (a charity that fights malaria in the developing world). For those concerned about human welfare, the choice should be clear. Donations to Moveon.org may or may not affect public policy, and if they do, the effect may be either good or bad–that is a matter for debate. But donations to Against Malaria definitely save lives. No one disputes that.

There are exceptions to the rule that one should not fight for causes. Sometimes, people find it necessary to fight for a cause, despite that the cause is obviously and uncontroversially good–as in the case of fighting to end human rights violations in a dictatorial regime. In this case, one’s opponents are simply corrupt or evil. Occasionally, a person knows some cause to be correct, even though it is controversial among the general public. This may occur because the individual possesses expertise that the public lacks, and the public has chosen to ignore the expert consensus. But these are a minority of the cases. Most individuals fighting for causes do not in fact know what they are doing.

He concludes,

Popular wisdom often praises those who get involved in politics, who vote in democratic elections, fight for a cause they believe in, and try to make the world a better place. We tend to assume that such individuals are moved by high ideals and that, when they change the world, it is usually for the better.

The clear evidence of human ignorance and irrationality in the political arena poses a serious challenge to the popular wisdom. Lacking awareness of basic facts of their political systems, to say nothing of the more sophisticated knowledge that would be needed to reliably resolve controversial political issues, most citizens can do no more than guess when they enter the voting booth. Far from being a civic duty, the attempt to influence public policy through such arbitrary guesses is unjust and socially irresponsible. Nor have we any good reason to think political activists or political leaders to be any more reliable in arriving at correct positions on controversial issues; those who are most politically active are often the most ideologically biased, and may therefore be even less reliable than the average person at identifying political truths. In most cases, therefore, political activists and leaders act irresponsibly and unjustly when they attempt to impose their solutions to social problems on the rest of society.

…Political leaders, voters, and activists are well-advised to follow the dictum, often applied to medicine, to “first, do no harm.” A plausible rule of thumb, to guard us against doing harm as a result of overconfident ideological beliefs, is that one should not forcibly impose requirements or restrictions on others unless the value of those requirements or restrictions is essentially uncontroversial among the community of experts in conditions of free and open debate. Of course, even an expert consensus may be wrong, but this rule of thumb may be the best that such fallible beings as ourselves can devise.

So, the next time you get the itch to raise awareness about some controversial political issue, Huemer suggests…

The Effects of Indian Child Labor Laws

A recent working paper looks at the effects of India’s 1986 anti-child labor law. Once again, good intentions and actual outcomes are at odds with one another:

The estimated effect of the ban is to increase relative employment among children under the age of 14. Having an underage sibling leads to a 0.3 percentage point increase in the likelihood of engaging in work after the ban for the very young. While this point estimate is small, it is both statistically and economically significant; the pre-ban proportion of children employed in that age range is only 2 percent so the effect of the ban is to increase employment by 15% over the mean for this group. The ban increases the probability of employment by 0.8 percentage points (5.6% over the mean) for young children ages 10-13. However, older children ages 14-17 overall are unaffected by the ban. The effect for this group is both small relative to the mean and statistically insignificant. Again, the largest increase in child labor is in agriculture…which is consistent with the partial mobility case of the two-sector model where there is restricted entry into manufacturing (pg. 22).

The authors then look at five measures of household welfare:

- Per capita expenditure.

- Per capita food expenditure.

- Caloric intake per capita.

- Staple share of calories; i.e., “a measure of household nutritional adequacy in the presence of caloric needs that are unknown or variable across households. [The] logic is that if households attach a high disutility to having caloric intake below caloric needs, they will substitute towards the cheapest sources of calories (staples)” (pg. 25).

- Household index asset; i.e., “a set of variables that capture the quality and quantity of housing, the type of energy used for cooking and lighting, and the quantity of electricity used (which is likely to be correlated with the number of appliances and durables used by the household” (pg. 25).

Their findings?

We find a negative and statistically significant point estimate of the ban’s effect on four out of five welfare measures. The one exception is caloric intake per capita which has a positive but not statistically significant coefficient. This is consistent with households near-subsistence – the ones likely to be most affected by the ban – being unable to cut back on calories and instead reducing other aspects of household welfare (consuming more less tasty staples or selling assets) as well as the idea that increased child labor for these households may increase household caloric requirements and thereby constrain households from adjustment on this margin. However the changes for all of the welfare measures are quantitatively small – about 0.01 standard deviations of the pre-ban cross-section – and the standard errors are small enough to rule out large positive or negative effects of the ban (pg. 26).

Nonetheless, “we take this as evidence that the ban makes these households unambiguously worse off” (pg. 5). They conclude,

This paper is the first empirical investigation of the impact of India’s most important legal action against child labor. While the Child Labor (Prohibition and Regulation) Act of 1986 prevented employers from employing children in certain sectors and increased regulation of child labor in non-family run businesses, the net result of this ban appears to be an increase in child labor in some families. We find that child wages decrease in response to such laws and poor families send out more children into the workforce. Due to increased employment, affected children are less likely to be in school. These results are consistent with a two sector model with some frictions on mobility across sectors where the ban is more stringently enforced in one sector than the other. Importantly, we also examine the overall welfare effects of the ban on households. Along various measures of household consumption and expenditure, we find that the ban leads to small decreases in household welfare.

This paper does not intend to suggest that all child labor bans are useless. In fact, well formulated and implemented bans could absolutely help in eliminating child labor; but as we do in this case, research would have to examine how a decrease in child labor affects child and household welfare (Baland and Robinson (2000); Beegle, Dehejia and Gatti (2009)). To echo the reasoning in Basu (2004): “Legal interventions, on the other hand, even when they are properly enforced so that they do diminish child labor, may or may not increase child welfare. This is one of the most important lessons that modern economics has taught us and is something that often eludes the policy maker” (pg. 30).

This isn’t all that surprising. Consider Paul Krugman:

In 1993, child workers in Bangladesh were found to be producing clothing for Wal-Mart, and Senator Tom Harkin proposed legislation banning imports from countries employing underage workers. The direct result was that Bangladeshi textile factories stopped employing children. But did the children go back to school? Did they return to happy homes? Not according to Oxfam, which found that the displaced child workers ended up in even worse jobs, or on the streets–and that a significant number were forced into prostitution.

The 1997 UNICEF State of the World’s Children report had similar findings:

The consequences for the dismissed children and their parents were not anticipated. The children may have been freed, but at the same time they were trapped in a harsh environment with no skills, little or no education, and precious few alternatives. Schools were either inaccessible, useless or costly. A series of follow-up visits by UNICEF, local non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and the International Labour Organization (ILO) discovered that children went looking for new sources of income, and found them in work such as stone-crushing, street hustling and prostitution — all of them more hazardous and exploitative than garment production. In several cases, the mothers of dismissed children had to leave their jobs in order to look after their children.

In cases like this, legislation is rarely the answer. In fact, according to economist Robert Whaples,

Most economic historians conclude that…legislation was not the primary reason for the reduction and virtual elimination of child labor between 1880 and 1940 [in the United States]. Instead they point out that industrialization and economic growth brought rising incomes, which allowed parents the luxury of keeping their children out of the work force. In addition, child labor rates have been linked to the expansion of schooling, high rates of return from education, and a decrease in the demand for child labor due to technological changes which increased the skills required in some jobs and allowed machines to take jobs previously filled by children. Moehling (1999) finds that the employment rate of 13-year olds around the beginning of the twentieth century did decline in states that enacted age minimums of 14, but so did the rates for 13-year olds not covered by the restrictions. Overall she finds that state laws are linked to only a small fraction – if any – of the decline in child labor. It may be that states experiencing declines were therefore more likely to pass legislation, which was largely symbolic.[ref]This is true of most sweatshop conditions.[/ref]

The road to hell and all that.

How Do Professors Vote?: 2017 Update

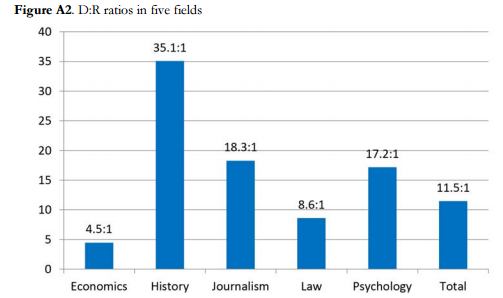

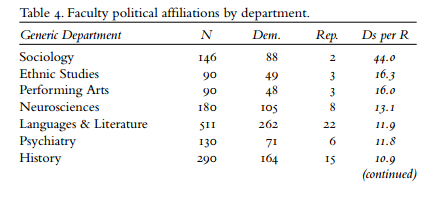

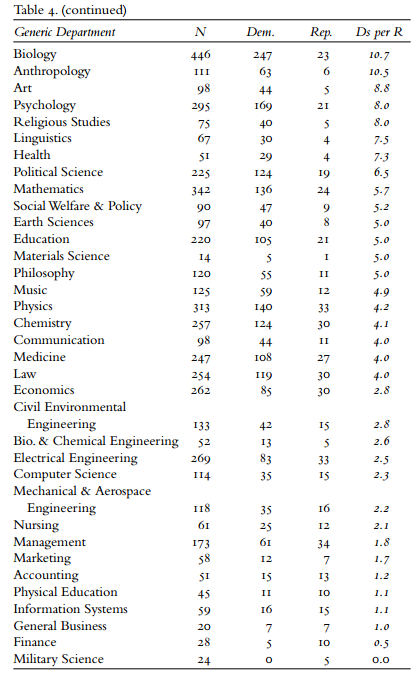

Earlier this year, I highlighted a 2016 study that unsurprisingly found that professors vote Democrat. The same researchers released an updated version of the study, having accidentally omitted two Florida universities. Of course, this didn’t change the outcome much:

The findings for the two omitted Florida universities, the University of Miami and the University of Florida, are consistent with the findings in our initial sample of 40 institutions. With the present addendum, our revised investigation now covers 42 top universities. In the new grand set, the either registered-Democrat-or-registered-Republican faculty from the newly added universities constitutes 6.1 percent of that of faculty of all 42 schools. As it turns out, the overall Democrat to Republican ratio (or, D:R ratio) changes so little that it is the same to the first decimal point, 11.5:1. Three of the five disciplinary ratios change slightly (pg. 56).

These findings are consistent with previous research. As I pointed out in my last post, economics departments tend to be more politically diverse than other social sciences. You can see the political diversity of various departments below, with the most diverse toward the bottom.

New Draft Report Covering a Decade of Refugees

A draft report by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services found that between 2005 and 2014, refugees brought in $63 billion more in government revenue than they cost. As reported by The New York Times,

The draft report…contradicts a central argument made by advocates of deep cuts in refugee totals as President Trump faces an Oct. 1 deadline to decide on an allowable number. The issue has sparked intense debate within his administration as opponents of the program, led by Mr. Trump’s chief policy adviser, Stephen Miller, assert that continuing to welcome refugees is too costly and raises concerns about terrorism.

Advocates of the program inside and outside the administration say refugees are a major benefit to the United States, paying more in taxes than they consume in public benefits, and filling jobs in service industries that others will not. But research documenting their fiscal upside — prepared for a report mandated by Mr. Trump in a March presidential memorandum implementing his travel ban — never made its way to the White House. Some of those proponents believe the report was suppressed.

Well, when you build an entire campaign on anti-immigration/refugee rhetoric, what else can you do?

Why Trump Won, A Reminder

So we’ve got a lot of people acting as though the election of Donald J. Trump represents a seismic shift in the American electorate and–just maybe!–a prelude to the Fourth Reich. This is just a reminder that the data don’t bear that out.

It’s not exactly news–Slate Star Codex carried it right after the election–but it bears repeating. So here’s the update from Matt Bruenig: The Boring Story of the 2016 Election.

Donald Trump did not win because of a surge of white support. Indeed he got less white support than Romney got in 2012. Nor did Trump win because he got a surge from other race+gender groups. The exit polls show him doing slightly better with black men, black women, and latino women than Romney did, but basically he just hovered around Romney’s numbers with every race+gender group, doing slightly worse than Romney overall.

However, support for Hillary was way below Obama’s 2012 levels, with defectors turning to a third party. Clinton did worse with every single race+gender combo except white women, where she improved Obama’s outcome by a single point. Clinton did not lose all this support to Donald. She lost it into the abyss. Voters didn’t like her but they weren’t wooed by Trump.

Bruenig goes on to explain why this narrative is so underplayed. Which is: nobody likes it. I’ll let you read Bruenig’s analysis on this point (I basically agree with it), but here’s the point: any discussion of what’s happening in American politics should adhere to the basic facts. Trump did a little worse than Romney. Clinton did a lot worse than Obama. Ergo the defining factor was Clinton’s deep unpopularity.

Last thought: she’s been in the press a lot since the end of the election. It even sounds like she wants to try again. Will she try? Will she succeed (in getting on the ballot)? What will that look like?

Immigrant Integration: European Edition

I’ve written before about how strict labor laws in Europe may be hindering immigrant integration. While I still think these may be barriers to integration, Europe is doing better than is often reported. As Tyler Cowen explains in Bloomberg,

Debates over immigration are fraught with misconceptions. One of the most common is that the integration of Muslims into societies in Western Europe has gone very badly, in large part because terror attacks loom so large in the news. Those attacks are a very real problem, yet they do not reflect the typical reality. A new study from the Bertelsmann Stiftung in Germany shows that Muslim integration in Europe is in fact proceeding at a reasonable pace.

The survey included more than 1,000 Muslims in Germany and about 500 in Austria, France, Switzerland and the U.K. (both immigrants and children of immigrants were included, though not recent refugees). Although this is hardly the first study of its kind, the results offer considerable hope for societies facing integration challenges: The stereotype of an uneducated, unemployed, easily radicalized Muslim migrant does not fit the facts.

The first sign of integration is language skill. About three-quarters of the Muslims born in Germany report German as their first language; 46 percent of foreign-born Muslims do. Overall, language skills improve with each generation, and migrants seem to be resourceful in finding ways to learn an adopted country’s tongue. Muslims immigrants to France and the U.K. often arrive knowing the languages of their new countries.

Only about one in 10 French Muslims report leaving school before age 17; the American high school graduation rate for all attendees is lower, at 83 percent. In Germany, employment for Muslim immigrants is on a par with employment for non-Muslims, though Muslim wages are lower. The rate of unemployment for French Muslims is a disappointing 14 percent, but that looks less troubling when you consider that migrants are relatively young and French youth unemployment as a whole is about 25 percent. Labor market reforms and better economies can help integrate foreign migrants, and Europe is currently showing decent economic growth, again reasons for hope.

Nor do Muslims huddle in Muslim-only communities, apart from the broader population. Some 87 percent of Swiss Muslims report having frequent or very frequent social contact with non-Muslims. In both Germany and France that number is 78 percent, again a sign of assimilation. It is lower in the U.K. (68 percent) and Austria (62 percent), but even those figures show plenty of social intermingling. And migrants across countries report feeling a close connection to the countries they live in, from a high of 98 percent (Switzerland) to a low of 88 percent (Austria).

Cowen continues,

The study also suggests that integration works better when the migrants are relatively numerous, perhaps because they can create mutual support services. But making that point is unlikely to win many European elections…The good news is that Western European integration of Muslims is further along than many people believe. The bad news is that the process of integration entails significant social change and change sometimes brings turmoil. The human race is improving at this broader challenge only slowly.

Houston, Hurricanes, and History

Economic and policy historian Phillip Magness has an enlightening post on Houston’s Harvey situation:

Older generations remember earlier storms and hurricanes that produced similar effects going back decades, although you have to return to December 6-9, 1935 to find an example that compares to Harvey’s stats.

Houston was a much smaller city in 1935, both in population and in geographical spread. But by some metrics the 1935 flood was even more severe. Buffalo Bayou – the main waterway through downtown – peaked at over 54 feet. Harvey, in all its devastation, hit “only” 40 feet by comparison. The 1935 storm dropped less rain, the maximum recorded being about 20 inches to the north of town where Houston’s main airport now sits. But it was also complicated by the problem of severe storms upstream that flowed into town and caused almost all of the other creeks and bayous that flooded last weekend to exceed their banks. Reports at the time noted that as much as 2/3rds of what was then rural and unpopulated farmland in surrounding Harris County saw flooding. Those areas are now suburbs today.

The effects of the 1935 flood on populated areas are also eerily similar to what we saw on television over the weekend. I recommend watching this film of the aftermath for comparison. All of downtown was underwater, as the film shows. People were stranded on rooftops as rivers of water emerged around them. There are even clips of rescuers navigating the streets of neighborhoods in small boats and canoes as water reached second and third stories on nearby buildings.

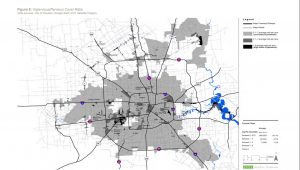

In the aftermath of the 1935 flood, the federal government commissioned an extensive study of Houston’s rainfall patterns. They produced

the following map of the Houston storm’s effects, showing unsettling similarities to what we just witnessed (note that this map does not include the areas to the north of town, where rainfall in 1935 was significantly higher. These are the suburbs that flooded along Cypress and Spring Creeks last weekend and the farmland that similarly flooded in 1935)

And therein lies the importance of history to understanding what we just witnessed in catastrophic form this weekend. Houston floods fairly regularly. In fact, downtown Houston has suffered a major flood on average about once a decade as far back as records extend in the 1830s.

He continues:

…tropical storms and hurricanes throughout the 20th century revealed Houston’s continued vulnerability to storms.

The reasons have to do almost entirely with topography and geography. Houston sits on the gulf of Mexico in an active hurricane zone that attracts large storms. But more significantly, Houston’s topography is extraordinarily flat. The elevation drop across the entire city and region is extremely modest. Most local waterways are slow-moving creeks and bayous that wind their way through town and eventually trickle into the shallow, marshy Trinity bay. Drainage is slow on a normal day. During a deluge, these systems fill rapidly with water that effectively has nowhere to go.

We’ve seen a flurry of commentators in the past few days attributing Houston’s flooding to a litany of pet political causes. Aside from the normal carping about “climate change” (which always makes for a convenient point of blame for bad warm weather events, even as environmentalists simultaneously decry the old conservative canard about blizzards contradicting Al Gore), several pundits and journalists have opportunistically seized upon Houston’s famously lax zoning and land use regulations to blame Harvey’s destruction on “sprawl” and call for “SmartGrowth” policies that restrict and heavily regulate future construction in the city.

According to this argument, Harvey’s floods are a byproduct of unrestricted suburban development in the north and west of the city at the expense of prairies that would supposedly absorb rainwater at sufficient rates to prevent natural disasters and that supposedly served this purpose “naturally” in the past.

There are multiple problems with this line of argument that suggest it is rooted in naked political opportunism rather than actual concern for Houston’s flooding problems.

And here they are:

- “flooding has been a regular feature of Houston’s landscape since the beginning of recorded history in the region. And catastrophic flooding – including multiple storms in the 19th century and the well-documented flood of December 1935 – predates any of the “sprawl” that has provoked these armchair urban designers’ ire.”

- “the flooding we saw in Harvey is largely a result of creeks and bayous backlogging and spilling over their banks as more water rushes in from upstream. While parking lot and roadway runoff from “sprawl” certainly makes its way into these streams, it is hardly the source of the problem. The slow-moving and windy Brazos river reached record levels as a result of Harvey and spilled over its banks, despite being nowhere near the city’s “sprawl.” The mostly-rural prairie along Interstate 10 to the extreme west of the city recorded some of the worst flooding in terms of water volume due to the Brazos overflow, although fortunately property damage here will be much lower due to being rural.”

- “the very notion that Houston is a giant concrete-laden water retention pond is itself a pernicious myth peddled by unscrupulous urban planning activists and media outlets. In total acres, Houston has more parkland and green space than any other large city in America and ranks third overall to San Diego and Dallas in park acreage per capita.”

- “a 2011 study by the Houston-Galveston Area Council…actually measured the ratio of impervious-to-pervious land cover within the city limits (basically the amount of water-blocking concrete vs. water-absorbing green land). The study used an index scale to measure water-absorption land uses. A low score (defined as less than 2.0 on the scale) indicates a high presence of green relative to concrete. A high score (defined as greater than 5.0) indicates high concrete and low levels of greenery and other water-absorbing cover. The result are in the map below, showing the city limits. Gray corresponds to high levels of pervious surfaces (or greenery). Black corresponds to high impervious surface use (basically either concrete or lakes that collect runoff). As the map shows, over 90% of the land in the city limits is gray, indicating more greenery and higher water absorption. Although they did not measure unincorporated Harris County, it also tends to be substantially less dense than the city itself.”

In short,

Houston’s flood problems are a distinctive feature of its topography and geography, and they long predate any “sprawl.” While steps have been taken over the years to mitigate them and reduce the severity of flooding, a rare but catastrophic event will unavoidably overwhelm even the most sophisticated flood control systems. Harvey was one such event – certainly the highest floodwater event to hit Houston in over 80 years, and possibly the worst deluge in its recorded history. But it is entirely consistent with almost 2 centuries of recorded historical patterns. In the grander scheme of causes for Harvey’s flooding, “sprawl” does not even meaningfully register.

The “Everyone is Racist” Quagmire

UPDATE: Although this post was published on August 24, 2017, it was written weeks ago. Notably, before Charlottesville. I’ll be writing a followup in light of recent events for the near future.

Despite the fact that overt, explicit racism is widely rejected and condemned within the United States, racially disparate outcomes remain endemic. One particular blatant example of this is the racially unequal justice system we have in this country. In super-short terms, blacks and whites use illegal drugs at about the same rates, but black people are more likely to be arrested, charged with more serious crimes, and serve longer sentences than whites.[ref]For the longer version, you can read my entire review of The New Jim Crow.[/ref]

Contemporary definitions of racism–of which there are basically two–attempt to explain why America continues to be a place with racially unfair outcomes even though overt racism has long since been marginalized. The first contemporary definition of racism is about systematic racism. According to this definition, prejudice is a feeling of animus against a person/people based on their race, discrimination is unequal treatment stemming from prejudice, and racism is an attribute of social systems and institutions where prejudice and discrimination have become ingrained. Accordingly, America can be a white supremacy without any white supremacists, because the overt prejudices of the past have been absorbed into our institutions (like the criminal justice system) and have taken on a life of their own. If the system is racially biased, then even racially unbiased people are not enough to get racial justice. It would be like playing a game with loaded dice. Even if the other players are 100% honest, their dice are still loaded, and so the outcome is still not fair. If you accuse them of cheating, they will be defensive because–in a sense–they are playing the game honestly. But as long as their dice are loaded (and yours are not), the game is still rigged.

Second, we have the idea of implicit racism. This is the idea that even people who really and sincerely believe that they are not racist may harbor unconscious racial prejudice. This is based on implicit-association tests and the theory that tribalism is basically hard-coded in human beings. These two findings–the empirical results of implicit-association tests and theories about the innateness of human tribalism–are not necessarily connected, but they come together in a phrase you’ve almost certainly heard by now: “everyone is racist.”

Thus, racial injustice can remain without overt racism because (in the case of systemic racism) racism is now located inside of institutions instead of inside of people and/or because (in the case of implicit racism) racism is now located inside people’s unconscious minds instead of their conscious minds.

So far, so good. Both of the new definitions (which are not mutually exclusive) provide promising avenues to understand ongoing racial disparity in the United States and seek to redress it. But this is where we run into a serious problem. As promising as these avenues might be, they certainly take us onto more ambiguous and complex territory than civil rights struggles of the past. The more overt racial injustice is, the simpler it is. Slavery and Jim Crow are not nuanced issues. But now we’re talking about how to fight racism in a world where nobody is racist anymore (at least not consciously). And just when things start to get tricky, the problem of perverse incentives rears its ugly head.

Perverse incentives are “incentives that [have] an unintended and undesirable result which is contrary to the interests of the incentive makers.”[ref]Wikipedia[/ref] In the fight against racial injustice there are basically two kinds of perverse incentive: institution and personal.

Institutional perverse incentives arise whenever you have an institution with a mission statement to eliminate something. The problem is that if the institution ever truly succeeds then it is essentially committing suicide and everyone who works for that institution has to go find not only a new job, but a new calling and sense of identity.

If conspiracy theories are your thing, then it’s not hard to spin lots of them based on this insight. Instead of fighting poverty, maybe government agencies perpetuate poverty in order to enlarge their budgets, expand their workforces, and enhance their prestige. But you don’t have to go that far. In practice, it’s far more likely that an institution dedicated to ending something will have two simple characteristics. First, it will exaggerate the threat. Second, it will be studiously uninterested in finding truly effective policies to combat the threat.

An agency that does this will successfully satisfy the economic and psychological self-interest of the people who who work for it. Economically, the bigger the threat the bigger the institution to oppose it. This is true regardless of whether we’re talking about a government agency arguing for a bigger slide of taxpayer revenue or a non-profit appealing for donations. Psychologically, the bigger the threat the easier it is for the people who work in the institution to feel good about themselves and not think too hard about whether or not they are really picking the most effective tools to eliminate whatever they’re supposed to be eliminating. In short: institutions that oppose a thing will gradually come to be hysterical and ineffectual because that’s in the best interest of the people who run those institutions.

This may sound all very hypothetical, so let me give you a specific example: the Southern Poverty Law Center. Politico Magazine recently came out with a very long article titled Has a Civil Rights Stalwart Lost Its Way? which makes a lot of sense when you keep the perils of perverse institutional incentives in mind as you’re reading it. The article points out that the SPLC has “built itself into a civil rights behemoth with a glossy headquarters and a nine-figure endowment, inviting charges that it oversells the threats posed by Klansmen and neo-Nazis to keep donations flowing in from wealthy liberals.”[ref]9-figure means hundreds of millions, by the way, so we’re not talking chump-change here.[/ref] It also notes that the election of Trump–while ostensibly bad for anti-racism efforts in the US–is unquestionably great for the SPLC, “giving the group the kind of potent foil it hasn’t had since the Klan.” So no, this isn’t just hypothetical theorizing. It’s what is happening already, to one of America’s most legendary anti-racism institutions.

The second set of perverse incentives are personal and basically class-based. Both the systematic and implicit definitions of racism evolved on elite college campuses, and the anti-racist theories that are based on these definitions are correspondingly unlikely to successfully reflect the interests and concerns of the genuinely underprivileged. They may be about the underprivileged, but they are adapted to–and serve the interests of–elites.

Consider first the case of a hypothetical young black man with a solidly middle- or upper-class background. Henry Louis Gates, Jr. observed that “the most ironic outcome of the Civil Rights movement has been the creation of a new black middle class which is increasingly separate from the black underclass,” and a 2007 PEW found that nearly 40 percent of blacks felt that “a widening gulf between the values of middle class and poor blacks” which meant that “blacks can no longer be thought of as a single race.” Thus, this young man faces a sense of double alienation: alienation from lower-class blacks and alienation from upper-class whites. Placing emphasis exclusively on the racial component of social analysis obscures the gulf between lower- and upper-class blacks and offers a sense of racial solidarity and wholeness. At the same time, it denies the actual privilege enjoyed by this person (after all, his neighborhood is not crime ridden and his schools are high-functioning) and therefore eases any sense of conflict or guilt at his comparative fortune.

The case is simpler for a hypothetical young white man with a privileged background, but (since this person enjoys even more advantages) the need for some kind of absolution is even more acute. Propounding the new definitions of racism allows low-cost access to that absolution. For an example of how this works, consider how the hilarious blog-turned-book Stuff White People Like discussed white people’s love of “Awareness.”[ref]Note that Stuff White People Like is, according to Wikipedia, “not about the interests of all white people, but rather a stereotype of affluent, environmentally and socially conscious, anti-corporate white North Americans, who typically hold a degree in the liberal arts.”[/ref] Stuff White People Like notes that “an interesting fact about white people is that they firmly believe that all of the world’s problems can be solved through “awareness.” Meaning the process of making other people aware of problems, and then magically someone else like the government will fix it.” The entry goes on: “This belief allows them to feel that sweet self-satisfaction without actually having to solve anything or face any difficult challenges.” Finally:

What makes this even more appealing for white people is that you can raise “awareness” through expensive dinners, parties, marathons, selling t-shirts, fashion shows, concerts, eating at restaurants and bracelets. In other words, white people just have to keep doing stuff they like, EXCEPT now they can feel better about making a difference.

The apotheosis of this awareness-raising fad is the ritual of “privilege-checking” in which whites, men, heterosexuals, and the cisgendered publicly acknowledge their privilege for the sake of feeling good about publicly acknowledging their privilege. In biting commentary for the Daily Beast, John McWhorter noted that:

The White Privilege 101 course seems almost designed to turn black people’s minds from what political activism actually entails. For example, it’s a safe bet that most black people are more interested in there being adequate public transportation from their neighborhood to where they need to work than that white people attend encounter group sessions where they learn how lucky they are to have cars. It’s a safe bet that most black people are more interested in whether their kids learn anything at their school than whether white people are reminded that their kids probably go to a better school.

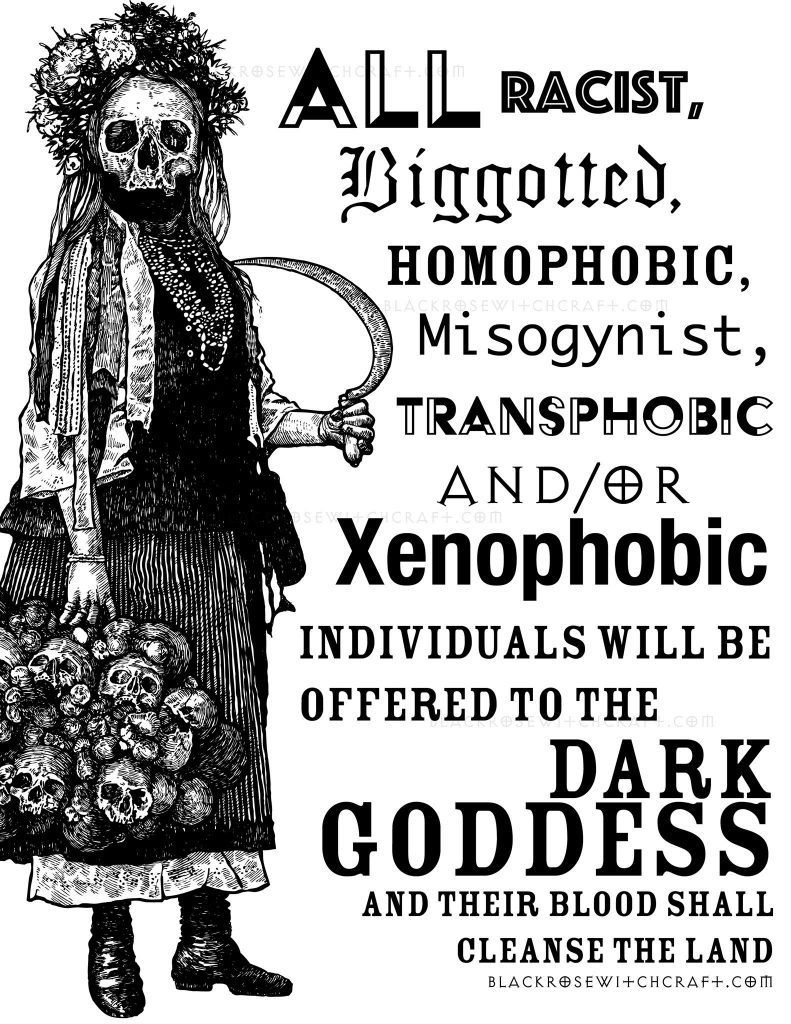

So we’re at a time when the complexity of racial injustice in the United States calls for new and nuanced definitions and theories of racism at precisely the time when–due to the past successes–the temptation to exaggerate racism and ignore effective anti-racism policies is also rising. The result? You might have a Facebook friend who will pontificate about how “everyone is racist” one day, and then post an image like this one the next:

So, you know, “we’re all racist” and also “if you’re racist, you deserve to die.” No mixed messages there, or anything.

Speaking of implicit bias, by the way, the actual results of Project Implicit’s testing are that nearly a third of white people have no racial preference or even a bias in favor of blacks. Once again, this doesn’t prove that racial justice has arrived and we can all go home. That’s absolutely not my point. It’s just another illustration that simplistic narratives about white supremacy don’t work as well in a post-slavery, post-Jim Crow world. The serious problems that remain are not as brutally self-evident as white people explicitly stating that the white race is superior.

Just to toss another complicating factor out there, researchers compared implicit bias to actual outcomes in undergraduate college admissions and found that despite the presence of anti-black implicit bias, the actual results of the admission process were skewed in favor of blacks rather than against them:

When making multiple admissions decisions for an academic honor society, participants from undergraduate and online samples had a more relaxed acceptance criterion for Black than White candidates, even though participants possessed implicit and explicit preferences for Whites over Blacks. This pro-Black criterion bias persisted among subsamples that wanted to be unbiased and believed they were unbiased. It also persisted even when participants were given warning of the bias or incentives to perform accurately.

If implicit bias can coexist with outcomes that are biased in the opposite direction, then what exactly are we measuring when we measure implicit bias, anyway?

I believe that both of the new definitions of racism have merit. The idea that institutional inertia can perpetuate racist outcomes long after the original racial animus has disappeared is reasonable theoretically and certainly seems to explain (in part, at least) the racially unequal outcomes in our criminal justice system. The idea that people divide into tribes and treat the outgroup more poorly–and that racial categories make for particularly potent tribal groups–is equally compelling. But the temptation to over-simplify, exagerate, and then coopt racial analysis for institutional and personal benefit is a genuine threat. As long as it’s possible to cash-in on anti-racism–financially and politically–then our progress towards racial justice will be impeded.

I am, generally speaking, a conservative. I don’t, by and large, share the worldview or policy proscriptions of those on the American left. But I do care about racial justice in the United States. I believe that the current discussion–or lack therefore–is significantly hampered by the temptation to profit from it. And I figure hey: maybe by speaking up I can contribute in a small way to shifting the conversation on race away from the left-right political axis and all the toxicity and perverse incentives that come with it.

More Economic Illiteracy from Journalists

I’ve lamented about this before. Funny enough, it was largely about the same source: The Guardian. A recent piece suggests that “neoliberalism” is responsible for, in the words of Forbes‘ Tim Worstall, the destruction of “everything that is good and holy about society.” This is based on a new IMF study that reviews the following:

Our assessment of the agenda is confined to the effects of two policies: removing restrictions on the movement of capital across a country’s borders (so-called capital account liberalization); and fiscal consolidation, sometimes called “austerity,” which is shorthand for policies to reduce fiscal deficits and debt levels. An assessment of these specific policies (rather than the broad neoliberal agenda) reaches three disquieting conclusions:

•The benefits in terms of increased growth seem fairly difficult to establish when looking at a broad group of countries.

•The costs in terms of increased inequality are prominent. Such costs epitomize the trade-off between the growth and equity effects of some aspects of the neoliberal agenda.

•Increased inequality in turn hurts the level and sustainability of growth. Even if growth is the sole or main purpose of the neoliberal agenda, advocates of that agenda still need to pay attention to the distributional effects.

In other words, it worries about financial openness and austerity. However, The Guardian describes it as such:

Three senior economists at the IMF, an organisation not known for its incaution, published a paper questioning the benefits of neoliberalism. In so doing, they helped put to rest the idea that the word is nothing more than a political slur, or a term without any analytic power. The paper gently called out a “neoliberal agenda” for pushing deregulation on economies around the world, for forcing open national markets to trade and capital, and for demanding that governments shrink themselves via austerity or privatisation. The authors cited statistical evidence for the spread of neoliberal policies since 1980, and their correlation with anaemic growth, boom-and-bust cycles and inequality.

Unfortunately for the author, that’s not quite accurate. The IMF researchers actually say,

There is much to cheer in the neoliberal agenda. The expansion of global trade has rescued millions from abject poverty. Foreign direct investment has often been a way to transfer technology and know-how to developing economies. Privatization of state-owned enterprises has in many instances led to more efficient provision of services and lowered the fiscal burden on governments.

Perhaps The Guardian author needs to be reminded that the IMF came out against protectionism last year in the midst of anti-trade rhetoric from politicians. Similarly, it released a report around the same time extolling the benefits of trade. Furthermore, the new IMF study qualifies its concerns:

The link between financial openness and economic growth is complex. Some capital inflows, such as foreign direct investment—which may include a transfer of technology or human capital—do seem to boost long-term growth. But the impact of other flows—such as portfolio investment and banking and especially hot, or speculative, debt inflows—seem neither to boost growth nor allow the country to better share risks with its trading partners (Dell’Ariccia and others, 2008; Ostry, Prati, and Spilimbergo, 2009). This suggests that the growth and risk-sharing benefits of capital flows depend on which type of flow is being considered; it may also depend on the nature of supporting institutions and policies.

…In sum, the benefits of some policies that are an important part of the neoliberal agenda appear to have been somewhat overplayed. In the case of financial openness, some capital flows, such as foreign direct investment, do appear to confer the benefits claimed for them. But for others, particularly short-term capital flows, the benefits to growth are difficult to reap, whereas the risks, in terms of greater volatility and increased risk of crisis, loom large.

This doesn’t strike me as a denunciation of “neoliberalism.” I’m going to follow Worstall’s lead on this one and refer to Max Roser’s work.

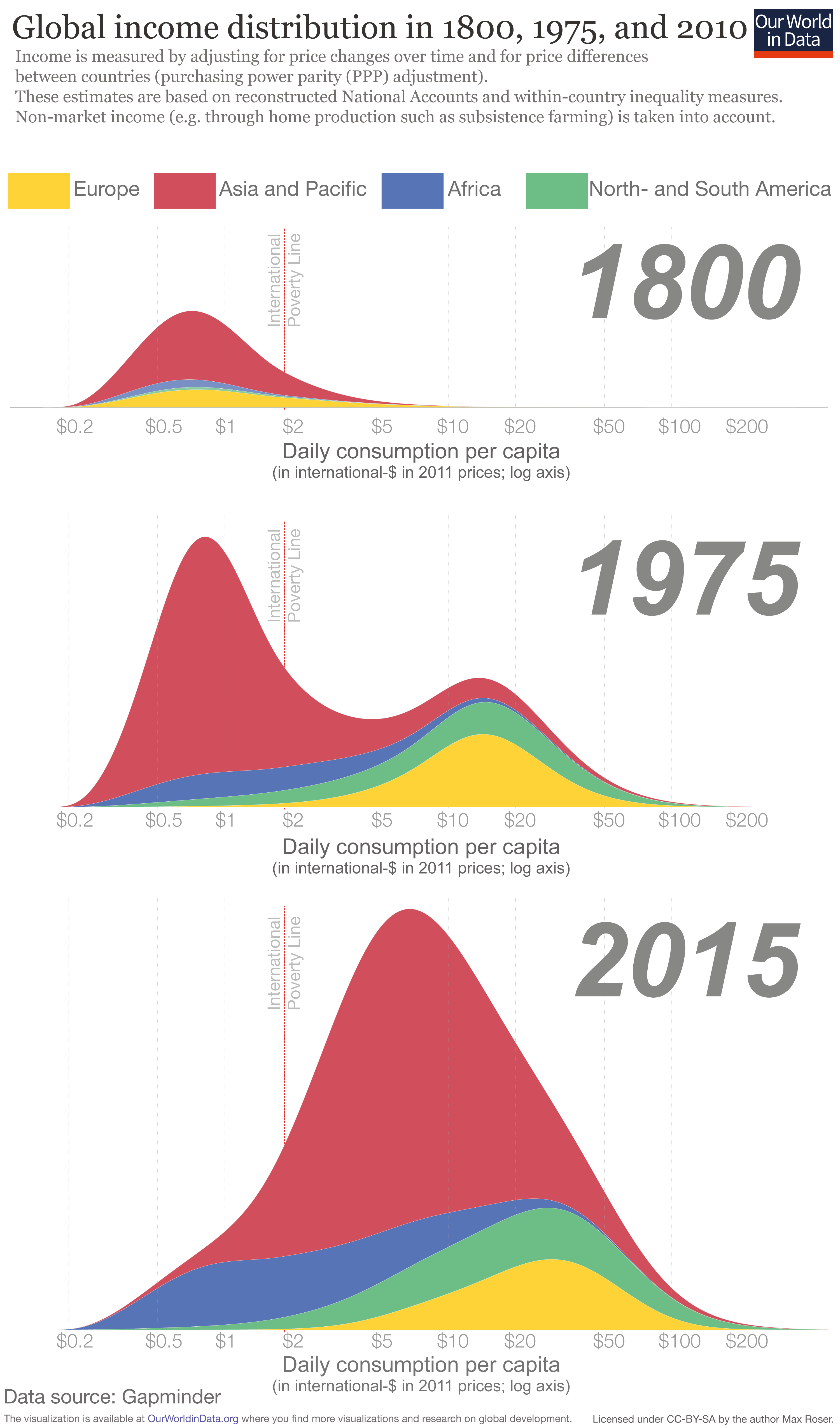

The distribution of incomes is shown at 3 points in time:

-

In 1800 only few countries achieved economic growth. The chart shows that the majority of the world lived in poverty with an income similar to the poorest countries in today. Our entry on global extreme poverty shows that at the beginning of the 19th century the huge majority – more than 80% – of the world lived in material conditions that we would refer to as extreme poverty today.

-

In the year 1975, 175 years later, the world has changed – it became very unequal. The world income distribution has become bimodal. It has the two-humped shape of a camel. One hump below the international poverty line and a second hump at considerably higher incomes – the world was divided into a poor developing world and a more than 10-times richer developed world.

-

Over the following 4 decades the world income distribution has again changed dramatically. The poorer countries, especially in South-East Asia, have caught up. The two-humped “camel shape” has changed into a one-humped “dromedar shape”. World income inequality has declined. And not only is the world more equal again, the distribution has also shifted to the right – the incomes of the world’s poorest citizens have increased and poverty has fallen faster than ever before in human history.

That’s right: global inequality is decreasing. The World Bank reports,

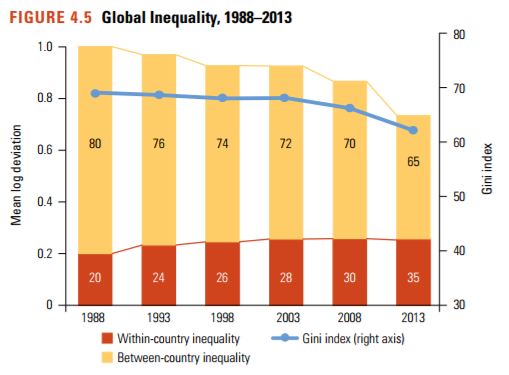

Globally, there has been a long-term secular rise in interpersonal inequality. Figure 4.3 shows the global Gini index since 1820, when relevant data first became available. The industrial revolution led to a worldwide divergence in incomes across countries, as today’s advanced economies began pulling away from others. However, the figure also shows that, in the late 1980s and early 1990s, the global Gini index began to fall. This coincided with a period of rapid globalization and substantial growth in populous poor countries, such as China and India.

…Global inequality has diminished for the first time since the industrial revolution. The global Gini index rose steadily by around 15 Gini points between the 1820s and the early 1990s, but has declined since then (see figure 4.3). While the various methodologies and inequality measures show disagreement over the precise timing and magnitude of the decline, the decline since the middle of the last decade is confirmed across multiple sources and appears robust. The estimates

presented in figure 4.5 show a narrowing in global inequality between 1988 and 2013. The Gini index of the global distribution (represented by the blue line) fell from 69.7 in 1988 to 62.5 in 2013, most markedly since 2008 (when the global Gini index was 66.8). Additional exercises confirm that these results are reasonably robust, despite the errors to which the data are typically subject (pg. 76, 81).

Harvard’s Andrei Shleifer has shown that between 1980 and 2005, world per capita income grew about 2% per year. During these 2.5 decades, serious hindrances on economic freedom declined, including the world median inflation rate, the population-weighted world average of top marginal income tax rates, and the world average tariff rates. “In the Age of Milton Friedman,” summarizes Shleifer, “the world economy expanded greatly, the quality of life improved sharply for billions of people, and dire poverty was substantially scaled back. All this while the world embraced free market reforms” (pg. 126).

Go away Guardian.