The New York Times has a recent article discussing new research on the minimum wage presented at the annual meeting of the American Economic Association:

John Horton of New York University conducted an experiment on an online platform where employers post discrete jobs — including customer service support, data entry, and graphic design — and workers submit a proposed hourly wage for completing them.

…At first glance, the findings were consistent with the growing body of work on the minimum wage: While the workers saw their wages rise, there was little decline in hiring. But other results suggested that the minimum wage was having large effects. Most important, the hours a given worker spent on a given job fell substantially for jobs that typically pay a low wage — say, answering customer emails.

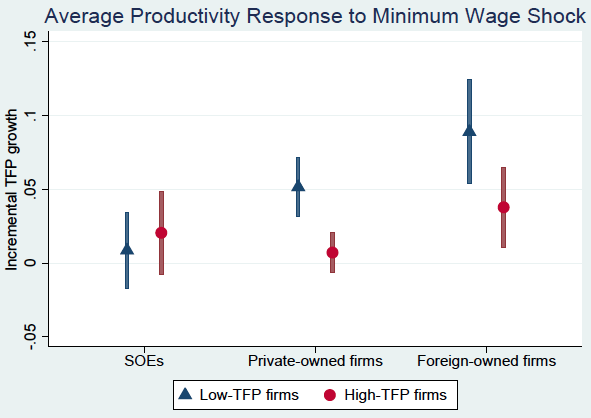

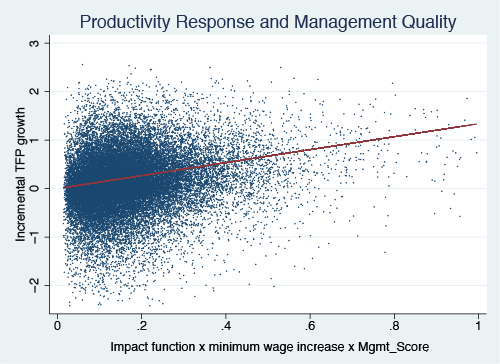

Mr. Horton concluded that when forced to pay more in wages, many employers were hiring more productive workers, so that the overall amount they spent on each job changed far less than the minimum-wage increase would have suggested…When the minimum wage increased, employers tended to hire workers who had earned higher wages in the past, suggesting that they were looking for a more productive work force.

If the pattern Mr. Horton identified were to apply across the economy, it would raise questions about whether increasing the minimum wage is as helpful to those near the bottom of the income spectrum as some proponents assume. The higher minimum wage could cost low-skilled workers their jobs, as employers rush to replace them with somewhat more skilled workers.

Another study found that when the minimum wage increases, employers may be put out of business. After identifying the ratings of thousands of restaurants in the San Francisco area, the researchers

found that many poorly rated restaurants tend to go out of business after a minimum-wage increase takes effect. By contrast, highly rated restaurants appear to be largely unaffected by minimum-wage increases, and over all, there is no substantial rise in restaurant closings after a minimum-wage increase.

The results are broadly consistent with a 2013 study…showing that a sizable minimum-wage increase in New Jersey resulted in many lost jobs as numerous businesses closed, but an almost offsetting number of new jobs as other businesses opened, which the authors argue were more productive.

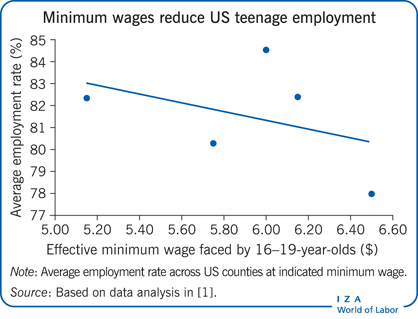

Just add this to the growing evidence of adverse effects of the minimum wage.