This post is part of the General Conference Odyssey.

Two thoughts from two different talks.

In “Blessed Are the Peacemakers”, Elder Burton said that:

We forget that we are not, and cannot be, totally independent of one another either in thought or action. We are part of a total community. We are all members of one family, as Paul reminded the Greeks at Athens when he explained that God “hath made of one blood all nations of men to dwell on all the face of the earth.” (Acts 17:26)

Although Elder Burton went in a different direction, that thought made me think about the talk before his, Elder LeGrand Richards’ What After Death?

I thought today that I would like to direct what I have to say to those parents who have lost children in death before they reached maturity and could enter into the covenant of marriage and have their own children here upon this earth. I reckon that there aren’t many families who haven’t had that experience.

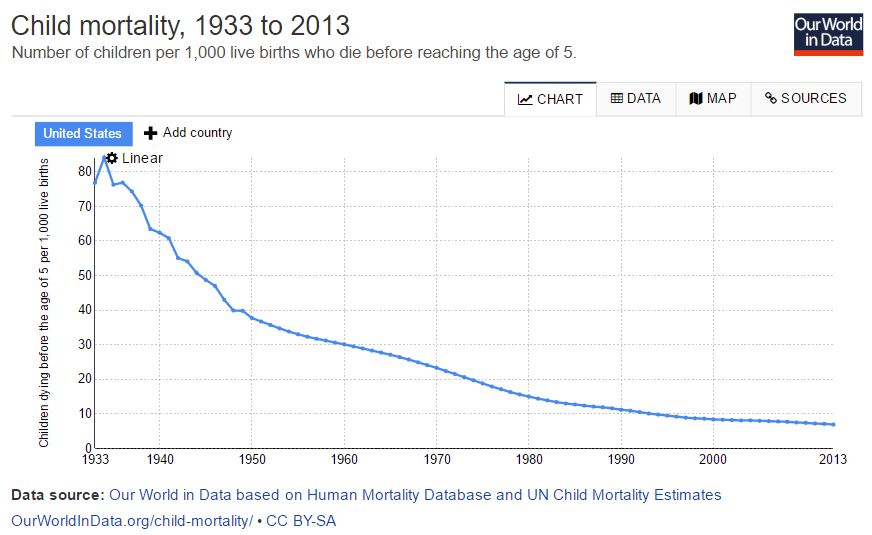

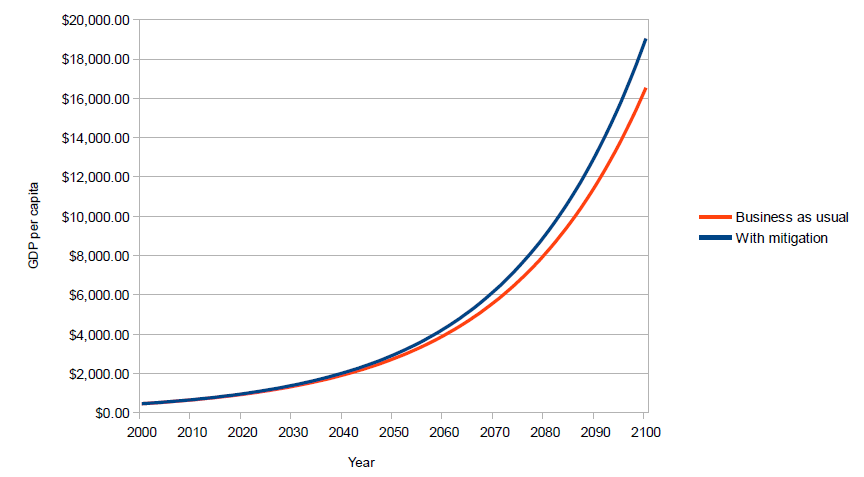

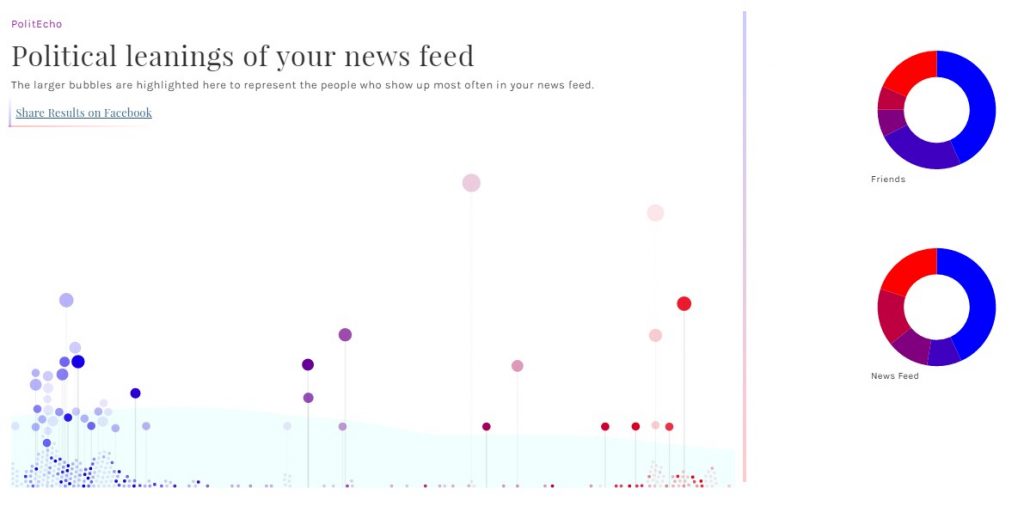

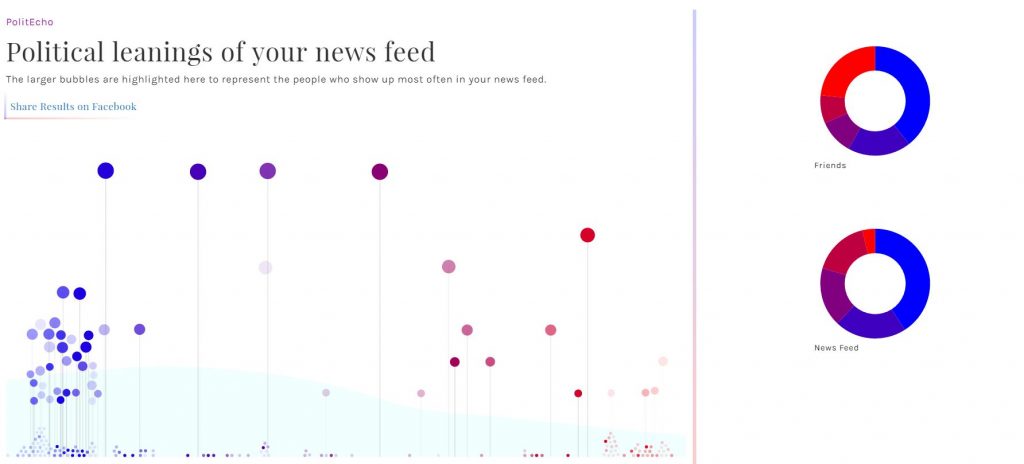

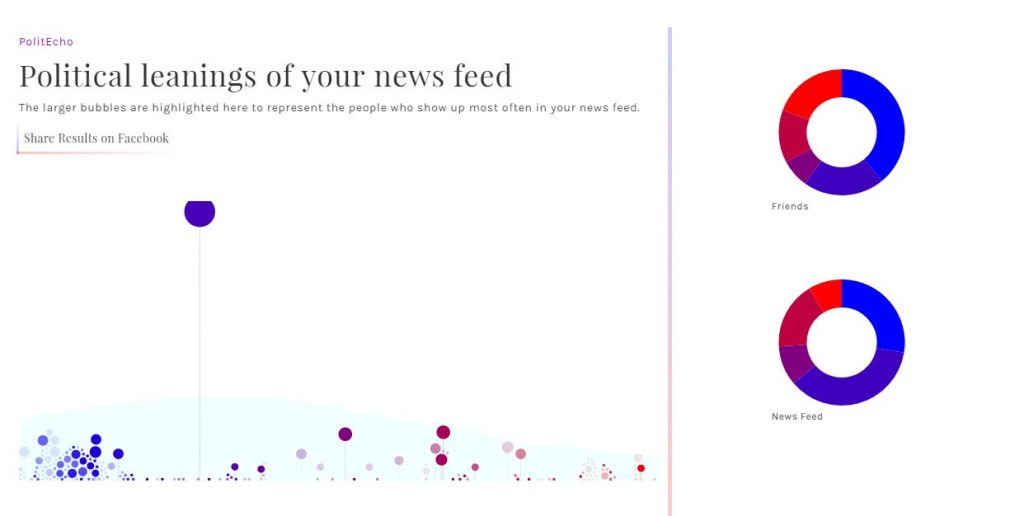

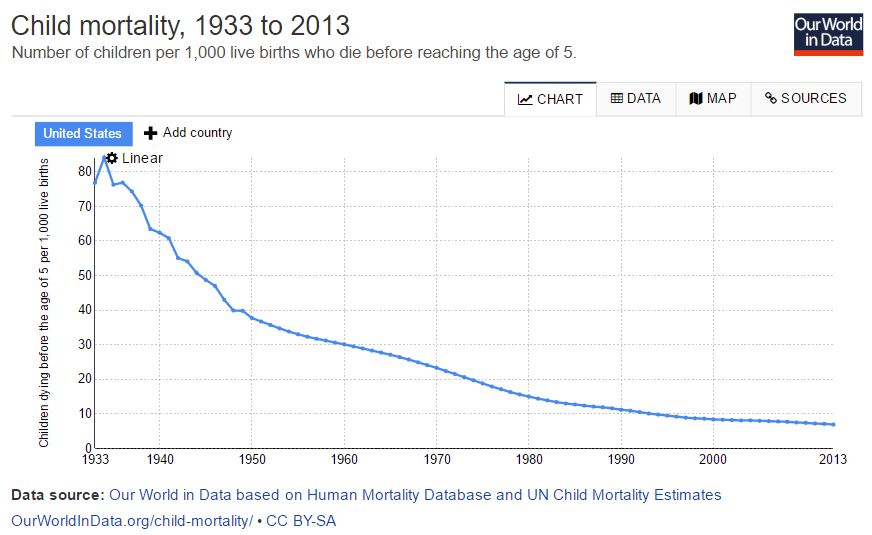

Elder Richards was born in 1886. I wondered what childhood mortality rates looked like for him, so I checked a great site (Our World in Data), but data for the United States only goes back to 1933.

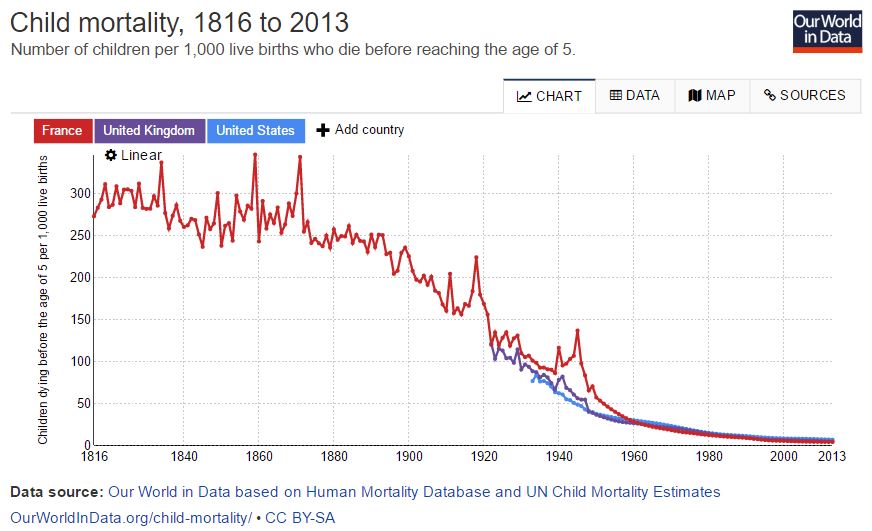

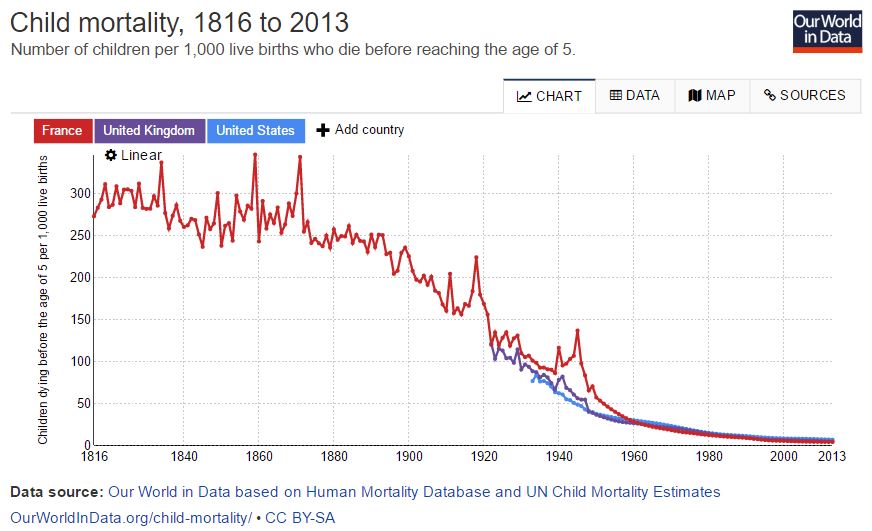

I added in the United Kingdom and then France to get an older data set.[ref]You can see from the graph that, while the lines are not identical, they follow a similar trend.[/ref] So, using France as a proxy, the kind of child mortality that Elder Richards would have been familiar was between 250 and 225 children per 1,000 dying before the age of 5.

By the time of this conference in 1974, the rate was down to about 20. For the most recent data (2013) the rate is about 4. In other words, the chances that a given newborn would die before age 5 have falledn from 25% to 2% to 0.4% from the time that Elder Richards was born to the time when he gave his talk to the time we are alive today. For a family with small children, the chance that none would die before the age of 5 was only 32% when Elder Richards was born. It was 92% in 1974. It is 98% today.

When he said, “I reckon that there aren’t many families who haven’t had that experience,” he was absolutely correct for his time, but the world has changed substantially since then.

The reason that I connect the two talks is that Elder Burton reminds us of how integral family is to our identity. As the saying goes: we’re social animals. And the first society is the family. This is a vital truth to who we are as human beings. I don’t think anything could possibly drive that lesson home than the unimaginable tragedy of losing a young child and having that family circle broken, at least temporarily.

I say “unimaginable” because to me it is. In my lifetime, having all your children survive to adulthood isn’t the exception; it’s the rule. But Elder Richards didn’t have to imagine it. As he discussed in his talk, two of his children died before they were old enough to be married.[ref]I realize my definition—dying before age 5—and Elder Richards’ definition—dying before being old enough to have married and have children—are not the same. I hope you can forgive the inaccuracy; I just went with the data I could quickly find.[/ref]

Right now I am reading The Clockwork Universe: Isaac Newton, the Royal Society, and the Birth of the Modern World. The author—Edward Dolnick—is at great pains to show how different the world of the 17th century was from the world of today. Back then, for example, no one knew what caused disease and nobody could do anything about it. From the Great Fire of London (1666) to a resurgence of Black Death (1665), the men and women who lived at that time lived their entire lives under the shadow of inexplicable, uncontrollable death.

Right now I am reading The Clockwork Universe: Isaac Newton, the Royal Society, and the Birth of the Modern World. The author—Edward Dolnick—is at great pains to show how different the world of the 17th century was from the world of today. Back then, for example, no one knew what caused disease and nobody could do anything about it. From the Great Fire of London (1666) to a resurgence of Black Death (1665), the men and women who lived at that time lived their entire lives under the shadow of inexplicable, uncontrollable death.

One thing Dolnick doesn’t understand, however, is how recently that has changed. Modernity may have dawned in the 17th and 18th centuries but—as the childhoold mortality figures show—disease and accident continued to make death a common, everyday experience well into the 20th century. Not long ago I read Samuel Brown’s incredible book, Through the Valley of Shadows. Althogh it’s a technical book in many ways, Brown sets up his main discussion (of living wills, advance directives, and intensive care units) with a discussion of “the dying of death.”

Before the Dying of Death, death was part of everyday experience. Death was recognized as horrifying, but people were able to understand it as part of the overall meaning of life and knew how to prepare for it when the time came. The understanding of death was broad enough to cross religious boundaries… By the end of the Dying of Death, Americans had contained the terror of death by simply ignoring it until the moment of crisis, but the sanctity of death had disappeared along with menacing presence. People found themselves newly unprepared when they came to die. Where many generations of humans had spent most of their lives preparing for their deathbed, modern Americans spent only hours to at most days, right in the their death agony, trying to come to terms with what was once called the King of Terrors… Since twentieth-century Americans had not generally spent their lives in the shadow of death, when they came to approach Death, as every human being inevitably does, they discovered just how culturally defenseless they were before it’s terrible power.[ref]Through the Valley of Shadows, page 27[/ref]

These changes occurred during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when basic understanding of the germ theory of disease led to incredibly advances in public health, but at that time there was still effectively nothing doctors could do to combat most diseases once they took hold. I was surprised at how recent this transition had occurred, but according to Brown, “physicians were mostly bad for your health until the recent past. The Baby Boomers are really the first generation born under the aegis of modern medicine.”[ref]Through the Valley of Shadows, page 32[/ref]

These changes occurred during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when basic understanding of the germ theory of disease led to incredibly advances in public health, but at that time there was still effectively nothing doctors could do to combat most diseases once they took hold. I was surprised at how recent this transition had occurred, but according to Brown, “physicians were mostly bad for your health until the recent past. The Baby Boomers are really the first generation born under the aegis of modern medicine.”[ref]Through the Valley of Shadows, page 32[/ref]

So, prior to the 1960s, doctors really couldn’t do anything at all to actively intervene in a wide variety of life-threatening medical emergencies. Since that time, however, our ability to postpone death has grown tremendously, to the point where ICUs frequently perform medical miracles. So, what has this newfound power achieved for us?

Well, it hasn’t all been good. Brown observes that “A major problem in contemporary society is that we combine our distaste for struggle or pain or disability with an unspeakable fear of death.”[ref]Through the Valley of Shadows, page 29[/ref] We have, in effect, stigmatized dying. As a result, “The dying–once celebrated as people with special wisdom who deserved the rapt attention of family and even strangers—[have] become America’s dirty secret.”[ref]Through the Valley of Shadows, page 29[/ref]

Additionally, ICUs—the frontlines in modern America’s war on death—have become places of trauma: “Many people leave the ICU with emotional scars as severe as those carried by combat veterans. Only a minority skate by without anxiety, depressing, or PTSD or some combination of the three.”[ref]Through the Valley of Shadows, page 167[/ref] This trauma is often the result of delusions, and rape delusions in particular: “it’s common for female patients to have memories of rape from urinary bladder catheters”[ref]Through the Valley of Shadows, page 140[/ref]. There are others, however:

The rape delusions associated with bladder catheters are haunting enough, but they don’t exhaust the list of terrible memories people often acquire in the ICU. Most of these frightening delusions relate to imprisonment, capture, or torture. Some feature aliens or homicidal doctors and nurses. More than a few incorporate the famous Capgras delusion, in which the important people in a person’s life are replaced by evil duplicates. These interpretations likely derive from the intense, paranoid attention that comes with high stress coupled with acute pain. The distressed brain tries to weave a meaningful narrative to explain why familiar faces (or people in professional gear and lab coats) are poking and prodding you as you are tied to a bed… some are frankly horrifying.

Let me explain why I’ve taking us on this long, long tangent. What I’m trying to explain is that as we’ve grown in our power to confront death, we have rediscovered an ancient truth: that power brings responsibility. This isn’t just about superheroes. It’s about ordinary men and women with no medical training and no preparation suddenly being told by doctors that it’s up to them to determine if their loved parent, or spouse, or child should live or die. But—precisely because death is so remote and even taboo—we’re completely and totally unprepared to shoulder this burden. As a result: many are crushed underneath it.

The majority of patients and families [emphasis added] come out of the ICU with post-traumatic stress, anxiety, or depression. They are more shell-shocked then combat veterans, according to an array of recent studies.[ref]Through the Valley of Shadows, page 5[/ref]

When it’s not about individuals staggering under the weight of responsibility they have no preparation for, it’s monstrous institutional inertia instead:

A friend’s elderly father, a devout Catholic, receive his last rites in a hospital. He struggled against the wrist restraints to create the sign of the cross in response to the priest’s gentle ministrations. The restraints intended to keep him from dislodging any medical equipment obstructed his desperate hunger to participate in the healthful rituals of the deathbed. He died later that day. It never occurred to the nurses and doctors to release the restraints for this final interaction with his priest. My friend and his family still remember that angry straining for divine connection, stymied by medical handcuffs.[ref]The Valley of Shadows, pages 137-138[/ref]

I share all this because if I just said, “Gee, now our children don’t die, and that’s weakened our appreciation for family,” it would sound banal (at best) or monstrously cruel (at worst). That’s not what I want to say. But I do want to illustrate how our medical prowess—despite absolutely being a blessing we should never surrender[ref]I don’t want any confusion on that point[/ref] has nonetheless presented us with fresh sets of problems we did not have to confront before.

When we stood powerless before death we had a kind of innocence. Now death seems to be far more contained, striking not children and spouses in their homes but the elderly in hospitals and hospices, and so we are all the less prepared to deal with it when it comes, as it surely must. That innocence is gone. Before we didn’t have to choose. Now—collectively and often individually—we do.

I feel like I need to say it again, and so I will one more time: I do not want to turn back the clock. I do not want to live in a world where having four children means probably having to watch at least one of them die in my arms. I want to live in a world where we can cure diseases and heal the sick. I thank God daily that my children are healthy and safe.

But this is a world that presents new and strange challenges. Elder Richards knew the pain of burying his own children, and this cemented in him a conviction of the importance of family relationships and the reality of life after death. He paid a high, high price for these blessings, one no parent would willingly pay.

The questions we have to ask are these: How are we going to acquire the wisdom and understanding to shoulder the responsibilities of technologically sophisticated modern medicine? How do we hold onto a fundamental understanding of the vital importance of family relationships in a world where—because death is so are—we so seldom have to learn through the painfully direct method of heartbreaking loss? How do we find the kind of life-sustaining, bedrock faith of Elder Richards without paying that staggeringly high cost?

I don’t know.

But I do believe that the best place to start is by understanding and cherishing the words and experiences of those who have paid that price before us, and then left bequeathed their words and testimonies to us who follow.

—

Check out the other posts from the General Conference Odyssey this week and join our Facebook group to follow along!

While Bill Watterson’s Calvin & Hobbes touched on childhood and life experience more generally, cartoonist Scott Hales delves into the details and nuances of Mormonism’s unique and somewhat odd culture while capturing the same kind of magic described above. His new graphic novel–

While Bill Watterson’s Calvin & Hobbes touched on childhood and life experience more generally, cartoonist Scott Hales delves into the details and nuances of Mormonism’s unique and somewhat odd culture while capturing the same kind of magic described above. His new graphic novel–

Trigger warnings” have been all the rage lately. They’ve sparked a

Trigger warnings” have been all the rage lately. They’ve sparked a