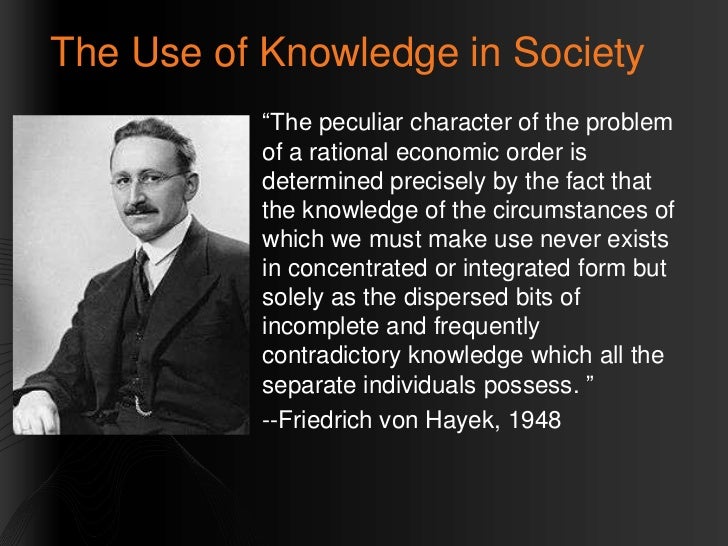

The latest issue of Econ Journal Watch has papers from the Mercatus-sponsored symposium “Economists on the Welfare State and the Regulatory State: Why Don’t Any Argue in Favor of One and Against the Other?” The issue features articles from economists like Robert Higgs, Arnold Kling, and Scott Sumner. However, the two that seem the most interesting to me are the articles by Swedish economist Andreas Bergh and social psychologist Jonathan Haidt. I’ve referenced Bergh’s work elsewhere due to his dispelling of several of myths regarding the Swedish welfare state (from both the Right and Left). His symposium contribution argues that a Hayekian welfare state can exist in theory by combining “low regulation with social insurance schemes that are not terribly vulnerable to the knowledge problem.”[ref]This might go well with philosopher Erik Angner’s view on Hayek and redistribution.[/ref]

In Haidt’s paper (with co-author Anthony Randazzo), the two surveyed economists and “found a relationship between views on empirical economic propositions and moral judgments.” Furthermore, in footnote #3, it says that Haidt is working on a book on capitalism and moral psychology. I imagine it will look something like his Zurich.Minds presentation.

Definitely worth checking out.