Climate change could have massive negative effects on the U.S. economy according to a new study:

We exploited random fluctuations in seasonal temperatures across years and states, using the richness of historical data available in the US. We employed a panel regression framework with the growth rate of gross state product (GSP) and average seasonal temperatures for each US state, and found that summer and autumn temperatures have opposite effects on economic growth. An increase in the average summer temperature negatively affects the growth rate of GSP. An increase in the autumn temperature positively affects this growth rate, although to a lesser extent. This suggests that previous studies’ aggregation of temperature data into annual temperature averages may mask the heterogeneous effects of different seasons.

The summer effect is particularly pronounced in data since 1990. This leads to a negative net economic effect of rising temperatures. This implies that the US economy is still sensitive to temperature increases, despite the adoption of adaptive technologies such as air conditioning (Barreca et al. 2015). Temperature also has a stronger effect in states with relatively high summer temperatures, most of which are located in the south.

Our analysis quantified the effect of rising temperatures across sectors of the US economy. We find that an increase in average summer temperature has a pervasive effect on all industries, not just the sectors that are traditionally assumed to be vulnerable to climate change…In our empirical analysis, an increase in the average summer temperature decreased the annual growth rate of labour productivity. An increase in the average autumn temperature had the opposite effect. Our analysis used data at the macroeconomic level, but it is consistent with existing studies of this relationship at the microeconomic level (Zivin and Neidell 2014, Cachon et al. 2012, Zivin et al. 2015).

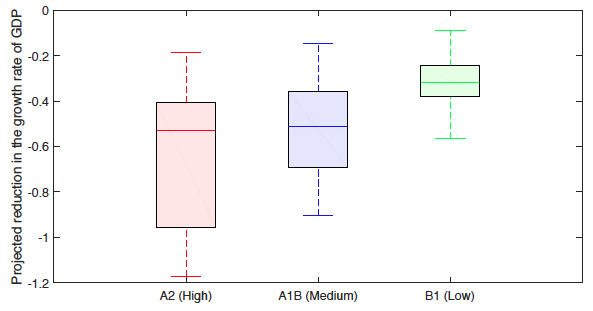

The authors find that the long-term effect of climate change would be a reduction in “the growth rate of US output by 0.2 to 0.4 percentage points by the end of the century. At the historical growth rate of US GDP of 4% per year, this would correspond to a reduction of up to 10%. The results are even more dramatic in the high emissions scenario (A2). Here, the reduction of economic growth could reach 1.2 percentage points, corresponding to roughly one-third of the historical annual growth rate of the US economy.”

You can see economist Bridget Hoffman explain the findings below:

These results echo Joseph Heath’s analysis of climate change’s effects on the global economy. But perhaps more important, it helps drive home his main point: climate change will drastically reduce economic growth over the next 100 years without intervention. But people will still be be significantly better off compared to us today even if we fail to act (check the GDP graph at about 0:46). They just won’t be as well off as they could have been.

Policy makers should consider both of these facts when discussing how to combat climate change.

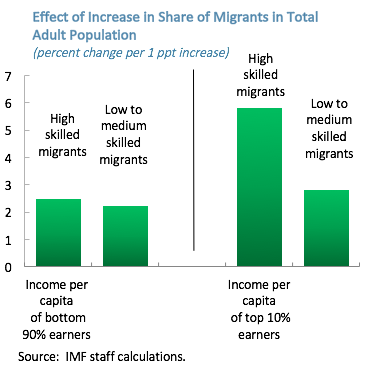

Technically, perhaps, but it’s difficult to feel bad for the top 10-15 percent.

Technically, perhaps, but it’s difficult to feel bad for the top 10-15 percent.

Estimates document that the bombing of South Vietnamese population centres backfired, leading more Vietnamese to participate in Viet Cong (VC) military and political activities and increasing VC attacks on troops and civilians. The initial deterioration in security entered the next quarter’s security score, increasing the probability of future bombing and hence leading to sustained increases in VC activity. Moreover, while US intervention aimed to build a strong state and engaged civic society that would provide a bulwark against communism after US withdrawal, bombing instead reduced the probability that the local government collected taxes, decreased access to primary schools, and reduced participation in civic organisations. To the extent that spillover effects of bombing on other locations exist, the impacts tend to go in the same direction as the effects on the locations that were bombed.

Estimates document that the bombing of South Vietnamese population centres backfired, leading more Vietnamese to participate in Viet Cong (VC) military and political activities and increasing VC attacks on troops and civilians. The initial deterioration in security entered the next quarter’s security score, increasing the probability of future bombing and hence leading to sustained increases in VC activity. Moreover, while US intervention aimed to build a strong state and engaged civic society that would provide a bulwark against communism after US withdrawal, bombing instead reduced the probability that the local government collected taxes, decreased access to primary schools, and reduced participation in civic organisations. To the extent that spillover effects of bombing on other locations exist, the impacts tend to go in the same direction as the effects on the locations that were bombed.

John Horton of New York University

John Horton of New York University  As some of my

As some of my  I don’t think I’ve ever mentioned this before on here, but, as some of you may have guessed, I go to therapy. I haven’t as of late for various reasons, but for a solid two years I went pretty much every other week. My interest in

I don’t think I’ve ever mentioned this before on here, but, as some of you may have guessed, I go to therapy. I haven’t as of late for various reasons, but for a solid two years I went pretty much every other week. My interest in